Section audio

Recall from Chapter III that, though social structures enable and constrain action, our actions produce and reproduce those structures. The healthcare system, for example, pursues the value of public interest because people created the system to implement that value.

Once created, people within the organization exercise their power to enable actions consistent with this value while constraining those actions opposed.

Herein lies the potential for change, for people can exercise their power to enable different values. They may face resistance from the organization. They may fail. They can try, however, and sometimes, they succeed. Let’s continue looking at the case from Appendix 1 for an example.

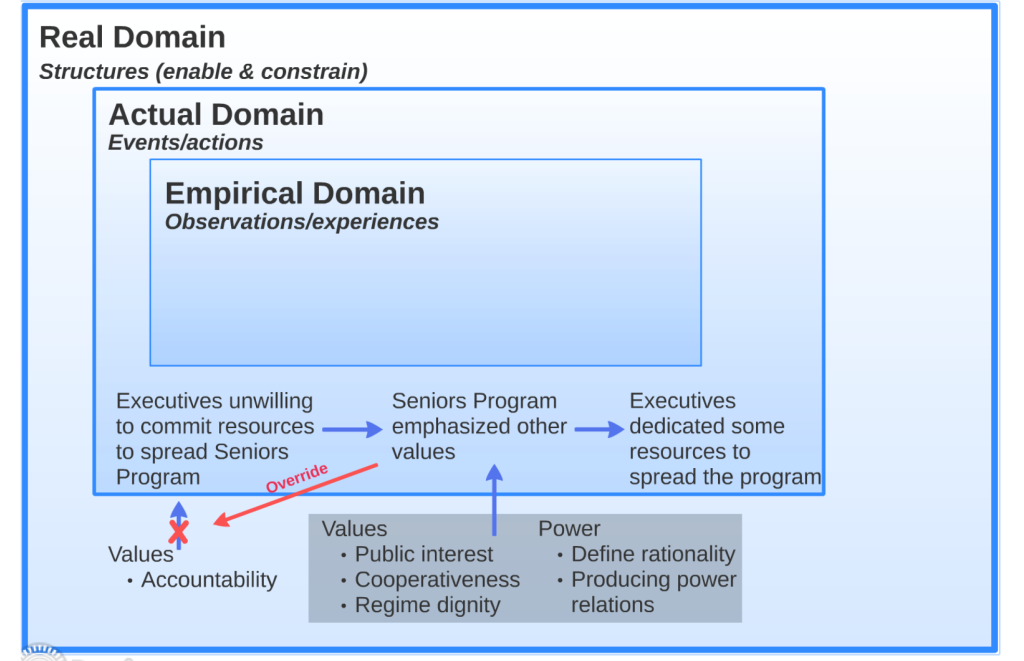

As described above, the value of accountability constrained managers’ willingness to use their resources to spread the Seniors Program to other communities. Had the fellowship stopped there, the program would have died. Despite this constraint on resourcing the program, different values in the organization did support its spread.

- The value of public interest drove healthcare workers, which the program delivered conclusively. Therefore, everyone wanted to see the program survive.

- The value of cooperativeness was present in the healthcare system, and so collaborating and working with other communities was supported.

- Plus, there was prestige to being a health authority that developed an innovation that the medical system adopted. Thus, there was some incentive to promote the spread of the program. This incentive speaks to the public sector value of regime dignity–the desire to look good.

The fellowship saw the importance of these other values to their organization and recognized their potential to enable the program’s spread. Thus, when seeking resources to support the Seniors Program’s spread, they emphasized its impact on the values of public interest, cooperativeness, and regime dignity. This approach successfully led some managers to support the program’s spread.

Doing this required individuals to exercise power. Their emphasizing alignment between their goal of spreading the program and the values of the organization was an example of defining rationality. They consequently received a bit of funding to continue spreading their innovation (an example of producing power relations).

The fellowship had keen insight into the different values active in their organization. Using that insight, they defined rationality to produce power relations that allowed them to access the funding needed to spread the program.

Though progress was much slower than the fellowship hoped, they still progressed nonetheless. The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

This example highlights the relationship between values and power. The next section will explore that relationship further.

Exercise: Can You Spot the Role of Power?

The above example identified the power tactic of defining rationality and producing power relations that Chapter VI introduced. Returning to Chapter VI:

- Identify which of Lukes’ four dimensions of power are present in the above example.

- Identify which of Fleming & Spicer’s faces and sites of power are present in the above example.

Key Takeaways

- By using tactics of power, such as producing power relations, defining rationality, and so on, individuals may overcome constraining structures.

A tactic of power where one party seeks to shape what others perceive as rational.

Two or more parties take action to form a working relationship with each other.