Chapter 6: Child Maltreatment

This chapter contains information about child abuse which may be triggering for some readers. |

DUTY TO REPORT

If you work with children in a family child care home or licensed child care facility, you are legally required or mandated to report and cannot shift the responsibility of reporting to your supervisor or to anyone else at your licensed facility.

Canadian Child and Family Services Act states “…every person who has reasonable grounds to believe that a child is in need of protection shall report the information to an officer or peace officer”.[1]

Introduction

Defining Child Maltreatment

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

Defining the Types of Child Maltreatment

Physical Abuse

Sexual Abuse

Emotional Abuse

Neglect

Exposure to Family Violence

The Impact of Child Maltreatment

Risk Factors for Maltreatment

Protective Factors

Preventative Maltreatment in Early Childhood Education Programs

Principles of Effective Prevention Programs

Service for Indigenous Families

Physical and Behavioural Signs of Child Maltreatment

Common Signs of Child Maltreatment

Signs of Maltreatment Related to Specific Types of Abuse

Understanding the Cause of Child Maltreatment

Background

Psycho-Social Model

Duty to Report

Who Do You Report Suspected Child Maltreatment to?

What to Include When You Report Suspected Child Maltreatment

After the Report is Made – What to expect

Working With Children Who Have Been Maltreated.

Summary

Resources

References

Chapter 6: Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define the five types of child maltreatment (physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, family violence and neglect).

- Identify risk factors for child maltreatment.

- Discuss protective factors and prevention strategies.

- List signs of each type of maltreatment.

- Explain what mandated reporting is and who it applies to.

Introduction

Ensuring that all children are safe and cared for is your primary responsibility. In accordance to the Canadian Child and Family Services Act: Section 12 states, you must report all suspected cases of child maltreatment to Social Services, and Child Protection agencies in your province or territory. In this chapter, you will begin to understand what child maltreatment is, what forms of child maltreatment there are, and how to report it to Child Protection Services (CPS).

Defining Child Maltreatment

Child maltreatment is defined as “… a misuse of power – a person with greater physical, intellectual, or emotional power and authority controls a child in a way that does not contribute to the child’s health, growth, and development.” [2] (Pimento & Kernested, 2019, p. 474).

You’ll work in close contact with a variety of young children and their families. It’s important you know and understand signs which indicate a child has been maltreated. Maltreatment can happen in a child’s home, or in the larger community. Offering a program that models respect toward all people is the first step in supporting all children in your care.

Families come from a range of values, experiences and beliefs in child-rearing which may be different than your own. It’s important to form relationships with families to better understand their ways of being with their children. These interactions may cause you to be angry or emotional. These feelings are based on your image of the child or your own experiences with maltreatment. Ensure you have self-care strategies in place if you feel this way.

If you find that a family or even other educators are maltreating a child, you are legally required by provincial or territorial law in Canada to report it. According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, 93% of all alleged child maltreatment is at the hands of the child’s direct relative. Children under one are maltreated at the highest rates. You’ll work to support both the child and their family if and when maltreatment has been confirmed [3].

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) is a global human rights treaty that outlines a full list of rights afforded to all children, up to the age of 18 (Government of Canada, 2021). It was adopted by the UN on November 20th, 1989. Before the UNCRC, there had been a desire to create a Declaration on the rights of children, but the majority of the international community wanted a “comprehensive statement on children’s rights which would be binding under international law” (United Nations, 2023).

The UNCRC is unique in that all but one State (country) has ratified it (agreed to follow)- making it unprecedented in the field of human rights (UN, 2023). The Canadian government signed the convention on November 20th, 1991, committing to the protection and promotion of these rights. November 20th is now known as National Child Day in Canada.

So how does the UNCRC relate to our topic of Child Maltreatment? The UNCRC speaks to the treatment of children in several of their articles, including:

|

Article 19: Protection from Violence. Governments must protect children from violence, abuse and being neglected by anyone who looks after them. |

|

Article 9: Keeping families together. Children should not be separated from their parents unless they are not being properly looked after – for example, if a parent hurts or does not take care of a child. Children whose parents don’t live together should stay in contact with both parents unless this might harm the child. |

|

Article 34: Protection from Sexual Abuse. The government should protect children from sexual exploitation (being taken advantage of) and sexual abuse, including by people forcing children to have sex for money, or making sexual pictures or films of them. |

|

Article 39: Recovery and Reintegration. Children have the right to get help if they have been hurt, neglected, treated badly or affected by war, so they can get back their health and dignity. |

Once a state (Country) agrees and signs the UNCRC they commit to protect children and promote the UNCRC. This means that the States, such as Canada, agree to support the UNCRC by creating laws that support the rights of children. Since signing the UNCRC the Canadian government has created laws to align with the UNCRC articles, such as

Further readings

If you are interested in seeing how Canada has upheld the UNCRC you can read a report by the Canadian Coalition for the Rights of Children (CCRC) – Rights in Principles, right in practice: Implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child in Canada. The CCRC is an organization that “monitors Canada’s progress in respecting, protecting and providing for children’s human rights – universal standards for the treatment of children set out in the UNCRC” (CCRC, 2012). In cooperation with other several civil society organizations conducted a community-based analysis to create the report.

Child maltreatment includes all types of abuse and neglect of a child under the age of 18 by a parent, caregiver, or another person in a custodial role (such as clergy, a coach, or a teacher) that results in harm, potential for harm, or threat of harm to a child. There are five common types of abuse and neglect: physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, family violence and neglect.[4]

Defining the Types of Child Maltreatment

In Canada, under the law, child maltreatment is broken down into 5 types of abuse, they include:

- Physical Abuse

- Sexual Abuse

- Emotional Abuse

- Family violence

- Neglect

To protect children and ensure they are safe you need to understand what child maltreatment is, the risk factors for child maltreatment, signs of different forms of child maltreatment and what you should do to support children and their families. Finally, you also need to know what to do in the event a child discloses to you or you suspect child maltreatment may be happening.

Physical Abuse

Physical abuse is a non-accidental physical injury to a child caused by a parent, caregiver, or other person responsible for a child and can include punching, beating, kicking, biting, shaking, throwing, stabbing, choking, hitting (with a hand, stick, strap, or other object), burning, or otherwise causing physical harm. Physical discipline, such as spanking or paddling, is not considered abuse as long as it is reasonable and causes no bodily injury to the child. Injuries from physical abuse could range from minor bruises to severe fractures or death.

Abusive Head Trauma

A form of physical abuse, which is important to understand, is abusive head trauma (AHT), formally referred to as a shaken baby syndrome. Why change the name? Abusive head trauma more accurately describes the seriousness of the injuries that occur to the head or the neck of children who are violently shaken thrown against or dropped on something hard (i.e. the floor or furniture) or hit in the head or neck with an object. [5]

Typically children younger than 2 years old are the most susceptible to this type of physical abuse, but it can happen to children under the age of five. It is caused by violent shaking and/or blunt impact. Due to the fact that young children have large heads, with heavy brains and weak neck muscles, they are more susceptible to this type of injury when a much larger and stronger youth or adult shakes them. When a child is shaken or thrown, it causes the brain to move inside the skull. The rapid change in direction causes the brain to move back and forth creating gaps between the brain and the skull – this causes bridging veins to rupture (break) as the space widens. It also causes the brain to hit the sides of the skull, the resulting injury can cause bleeding around the brain or on the inside back layer of the eyes. Nearly all victims of AHT suffer serious, long-term health consequences such as vision problems, developmental delays, physical disabilities, and hearing loss. At least one of every four babies who experience AHT dies from this form of child abuse. [6]

AHT often happens when a parent or caregiver is tired, frustrated or angry because of a child’s crying or not behaving in the way the parent or caregiver expects. The caregiver then shakes the child and/or hits or slams the child’s head into something in an effort to stop the crying or the behaviour. AHT is 100% preventable, one way is to educate parents and other caregivers that crying is normal and provide them with information on it. Make it clear about the consequences AHT has on the child and that shaking, throwing it hitting a child on hard surfaces is never an option. Support them if and when they are unable to deal with a child. Let them know that it is okay to put the child in a safe place and walk away and take a break. It’s okay to ask for help. Model appropriate ways to deal with a crying or fussy child [7].

AHT often happens when a parent or caregiver is tired, frustrated or angry because of a child’s crying or not behaving in the way the parent or caregiver expects. The caregiver then shakes the child and/or hits or slams the child’s head into something to stop the crying or the behaviour. AHT is 100% preventable, one way is to educate parents and other caregivers that crying is normal and provide them with information on it. Make it clear about the consequences AHT has on the child and that shaking, throwing it hitting a child on hard surfaces is never an option. Support them if and when they are unable to deal with a child. Let them know that it is okay to put the child in a safe place and walk away and take a break. It’s okay to ask for help. Model appropriate ways to deal with a crying or fussy child. [8].

Further readings

Information provided, in part by:

Nemours Children’s Health through its award-winning Nemours KidsHealth website. For more on this topic, Abusive head trauma, visit KidsHealth.org.

CDC: Centre for Disease Control and Prevention – Preventing Head Trauma, for more information visit CDC.gov.

Facts on Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma (Shaken Baby Syndrome) visit Saskatchewan Prevention Insitute.

Abusive Head Trama (Shaken Baby Syndrome) visit Nemours Kids Health

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting

Canada is made up of people from all over the world as a result, as an educator you may see things that you may find shocking, such as female genital mutilation (FGM). FGM comprises all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons. The practice has no health benefits for girls and women and causes severe bleeding and problems urinating, and later cysts, infections, as well as complications in childbirth and increased risk of newborn deaths. Female genital mutilation is classified into 4 major types:

Type 1: This is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans (the external and visible part of the clitoris, which is a sensitive part of the female genitals), and/or the prepuce/clitoral hood (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoral glans).

Type 2: This is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans and the labia minora (the inner folds of the vulva), with or without removal of the labia majora (the outer folds of skin of the vulva).

Type 3: Also known as infibulation, this is the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the labia minora, or labia majora, sometimes through stitching, with or without removal of the clitoral prepuce/clitoral hood and glans.

Type 4: This includes all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, e.g., pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing the genital area.

According to Unicef, 200 million girls have been subject to this form of violence. The majority of these girls come from one of 30 countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. FGM is usually done when girls are between 4-10 years of age. [9]

Corporal Punishment

Corporal punishment includes striking a child with or without an object, shaking, shoving, spanking and other forms of aggressive contact and is not permitted in a child care facility. The Child Care Regulations, 2015 states:

| SECTION 15:

(1) The following practices are not permitted methods of child management with respect to a c child receiving child care services in a facility: (a) corporal punishment; (b) physical, emotional or verbal abuse; (c) denial of necessities; (d) isolation; (e) inappropriate physical or mechanical restraint. (2) A licensee must: (a) develop a written policy with respect to child management that is consistent with subsection (1); and (b) ensure that all employees and volunteers who provide child care services at the facility comply with the policy required by clause (a).

|

Sexual Abuse

Child sexual abuse is a significant but preventable adverse childhood experience and public health problem. In Canada, sexual abuse is a criminal offence under the Criminal Code of Canada. The Criminal Code defines sexual abuse and exploitation as occurring when “…an older child, adolescent or adult takes advantage of a younger child or youth for sexual purposes. These acts can include a parent or other caregiver fondling a child’s genitals, penetration, incest, rape, sodomy, indecent exposure, and exploitation through prostitution or the production of pornographic materials” (Government of Canada, 2007). Sexual abuse is a criminal offence under the Criminal Code of Canada. Sexual abuse is defined by the Canada Evidence Act “the employment, use, persuasion, inducement, enticement, or coercion of any child to engage in, or assist any other person to engage in, any sexually explicit conduct or simulation of such conduct for the purpose of producing a visual depiction of such conduct; or the rape, and in cases of a caretaker or interfamilial relationships, statutory rape, molestation, prostitution, or other forms of sexual exploitation of children, or incest with children”

Statistics:

One out of 10 children are sexually abused before the age of 18 [10].

80% – 90% of child sexual abuse is perpetrated by someone the child or child’s family knows [11].

Emotional Abuse

Emotional abuse is the most common type of abuse and is hard to prove. Emotional abuse is a pattern of behaviour that impairs a child’s emotional development or sense of self-worth.

Emotional abuse can be defined as “.. the habitual verbal harassment of the child through disparagement, criticism, threat and ridicule” (Skuse, 1989, 1692). It also includes rejections and/or the withdrawal of love and affection both verbally and non-verbally.

| Terrorizing or threats of violence. | A climate of fear, placing the child in unpredictable or chaotic circumstances, bullying or frightening a child, threats of violence against the child or child’s loved ones or objects. |

| Verbal abuse or belittling: | Non-physical forms of overtly hostile or rejecting treatment. Shaming or ridiculing the child, or belittling and degrading the child. |

| Isolation/confinement | Adult cuts the child off from normal social experiences prevent friendships or makes the child believe that he or she is alone in the world. Includes locking a child in a room, or isolating the child from the normal household routines. |

| Inadequate nurturing or affection | Through acts of omission, does not provide adequate nurturing or affection. Being detached, uninvolved; failing to express affection, caring and love, and interacting only when absolutely necessary. |

| Exploiting or corrupting behaviour: | The adult permits or encourages the child to engage in destructive, criminal, antisocial, or deviant behaviour. |

Emotional abuse (or psychological abuse) is a pattern of behaviour that impairs a child’s emotional development or sense of self-worth. This may include constant criticism, threats, or rejection as well as withholding love, support, or guidance. Emotional abuse is often difficult to prove, and, therefore, child protective services may not be able to intervene without evidence of harm or mental injury to the child (Prevent Child Abuse America, 2016).[13]

Neglect

Neglect is the failure of a parent or other caregiver to provide for a child’s basic needs. Neglect generally includes the following categories:

| Failure to supervise physical harm | The child suffered physical harm or is at risk of suffering physical harm because of the caregiver’s failure to supervise or protect the child adequately. Failure to supervise includes situations where a child is harmed or endangered as a result of a caregiver’s actions (e.g., drunk driving with a child, or engaging in dangerous criminal activities with a child). |

| Failure to supervise sexual abuse | The child has been or is at substantial risk of being sexually molested or sexually exploited, and the caregiver knows or should have known of the possibility of sexual molestation and failed to protect the child adequately. |

| Permitting criminal behaviour | A child has committed a criminal offence (e.g., theft, vandalism, or assault) because of the caregiver’s failure or inability to supervise the child adequately |

| Physical neglect | The child has suffered or is at substantial risk of suffering physical harm caused by the caregiver(s)’ failure to care and provide for the child adequately. This includes inadequate nutrition/clothing, and unhygienic, dangerous living conditions. There must be evidence or suspicion that the caregiver is at least partially responsible for the situation. |

| Medical neglect - including dental. | The child requires medical treatment to cure, prevent, or alleviate physical harm or suffering and the child’s caregiver does not provide, or refuses, or is unavailable, or unable to consent to the treatment. This includes dental services when funding is available. |

| Psychiatric or psychological treatment | The child is suffering from either emotional harm demonstrated by severe anxiety, depression, withdrawal, or self-destructive or aggressive behaviour, or a mental, emotional or developmental condition that could seriously impair the child’s development. The child’s caregiver does not provide, or refuses, or is unavailable, or unable to consent to treatment to remedy or alleviate the harm. This category includes failing to provide treatment for school related problems such as learning and behaviour problems, as well as treatment for infant development problems such as non-organic failure to thrive |

| Abandonment | The child’s parent has died or is unable to exercise custodial rights and has not made adequate provisions for care and custody, or the child is in a placement and parent refuses/is unable to take custody. |

| Educational neglect | Caregivers Knowingly permit chronic truancy (5+ days a month), or fail to enroll the child, or repeatedly keep the child at home. If the child is experiencing mental, emotional or developmental problems associated with school, and treatment is offered but caregivers do not cooperate with treatment, classify the case under failure to provide treatment as well. |

| Emotional | An adults inattention to a child’s emotional needs, failure to provide psychological care. |

| Come up with a situation that would be an example of each type of abuse and each type of neglect. Keep these in mind to revisit in another Pause to Reflect feature later in the chapter. |

Exposure to Family Violence and Interpersonal Violence (including intimate-partner violence)

Family violence (interchangeable with domestic violence) refers to a child living in a situation where there is interpersonal violence, including children witnessing, hearing or being aware of violence perpetrated by one adult figure against another adult figure (the other parent, grandparent, a friend of the adult figure) or against another child. Children can witness many different forms of abuse in these situations including physical abuse, mental and emotional abuse, sexual abuse, intimidation, financial abuse and threats. Such situations may put the child at risk of physical, emotional or mental health harm.

Children may very well experience the violence themselves; however, even when they are not directly injured, exposure to traumatic events can cause social, emotional, and behavioural difficulties. Children exposed to domestic violence have often been found to develop a wide range of problems, including externalizing behaviour problems, interpersonal skill deficits, and psychological and emotional problems such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In addition, a Michigan study of preschool-aged children found that those exposed to domestic violence at home are more likely to have health problems, including allergies, asthma, frequent headaches and stomachaches, and generalized lethargy.

|

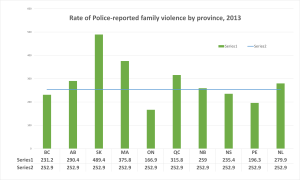

| Figure 1: Rate of police-reported family violence, by province 2013. (Statistics Canada, 2013) [15] |

Figure 1, demonstrates the severity of family violence across the provinces in 2013 as reported to the police. As we see Ontario has the lowest rate of 166.9 victims per 100,000 population, whereas Saskatchewan has the highest rate with 489.4 victims per 100,000 population. Canada’s average rate of police-reported violence was 252.9 victims per 100,000 of the population. Given the magnitude of the problem of children’s exposure to violence, early care and education programs are valuable services for children and families impacted by violence.

Intimate partner violence describes physical, sexual, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse. This type of violence can occur among heterosexual or same-sex couples and does not require sexual intimacy. Intimate partner violence can vary in frequency and severity. It occurs on a continuum ranging from one hit that may or may not impact the victim to chronic, severe beating. Witnessing family assault is among the most common victimizations experienced by toddlers (ages 2 to 5). Other common forms of victimization are assault by a sibling and physical bullying. [16]

| Direct witness to physical violence | The child is physically present and witnesses the violence between intimate partners |

| Indirect exposure to physical violence | Includes situations where the child overhears but does not see the violence between intimate partners; or sees some of the immediate consequences of the assault (e.g., injuries to the mother); or the child is told or overhears conversations about the assault |

| Exposure to emotional violence: | Includes situations in which the child is exposed directly or indirectly to emotional violence between intimate partners. Includes witnessing or overhearing emotional abuse of one partner by the other. |

| Exposure to non-partner physical violence |

A child has been exposed to violence occurring between a caregiver and another person who is not the spouse/partner of the caregiver (e.g., between a caregiver and a neighbour, grandparent, aunt or uncle). |

The Impact of Child Maltreatment [17]

Child maltreatment, encompassing both child abuse and neglect is a serious but potentially preventable public health issue that can have serious, long-term consequences for children, families, communities and society. It is clear that child maltreatment contributes significantly to the overall burden of adversity experienced by children and increases the risk of a range of negative outcomes. Maltreatment can produce both physical and psychological consequences, some immediately evident in childhood and

some with life-long effects. Child maltreatment not only has adverse consequences for the health of the maltreated individual but also produces immense financial costs to society. This includes proximal costs for direct services and support to families, as well as “downstream” costs such as those related to lost productivity, poor physical and mental health, and antisocial behaviour. [18]

Risk Factors for Maltreatment

Risk factors are any attribute, characteristic or exposure of an individual that increases the likelihood of developing a disease or injury – including emotional harm.[19] Although children are not responsible for the maltreatment inflicted on them, certain characteristics have been found to increase the risk of being mistreated. These characteristics may not be the direct causes of the maltreatment but a combination of individual, relational, community and societal factors contribute to the child maltreatment.

Individual Risk Factors for Victimization

- Children younger than 4 years of age

- Child’s temperament, insecure attachment

- Special needs that may increase caregiver burden (e.g., disabilities, mental health issues, and chronic physical illnesses)

Risk Factors for Perpetration

There are three (3) different levels of risk factors for the perpetrators of child maltreatment, which include Individual, Family and Community.

Individual Risk Factors – Parent

- Families’ lack of understanding of children’s needs, child development and parenting skills

- Parental history of child abuse and or neglect

- Substance abuse and/or mental health issues including depression in the family

- Parental characteristics such as young age, low education, single parenthood, a large number of dependent children, and low income

- Non-biological, transient caregivers in the home (e.g., mother’s male partner)

- Parental thoughts and emotions that tend to support or justify maltreatment behaviors

Family Risk Factors

- Social isolation

- Family disorganization, dissolution, and violence, including intimate partner violence

- Parenting stress, poor parent-child relationships, and negative interactions

- High conflict and negative communication styles.

- Parents in jail or prison

Community Risk Factors

- Community violence

- Concentrated neighbourhood disadvantage (e.g., high poverty and residential instability, high unemployment rates, and high density of alcohol outlets), and poor social connections.[20]

- Limited education opportunities.

- Easy access to drugs and alcohol

- Low community involvement – neighbours looking out for each other.

- Neighbourhoods with families that experience food insecurities.

Protective Factors

Protective factors may lessen the likelihood of children being abused or neglected. Protective factors have not been studied as extensively or rigorously as risk factors. Identifying and understanding protective factors are equally as important as researching risk factors.

Individual Protective Factors

- Caregivers who create safe, positive relationships with children

- Caregivers who practice nurturing parenting skills and provide emotional support

- Caregivers who can meet basic needs of food, shelter, education, and health services

- Caregivers who have a college degree or higher and have steady employment

Family Protective Factors

- Families with strong social support networks and stable, positive relationships with the people around them

- Families where caregivers are present and interested in the child

- Families where caregivers enforce household rules and engage in child monitoring

- Families with caring adults outside the family who can serve as role models or mentors

Community Protective Factors

- Communities that support families and take responsibility for preventing abuse[21]

- Communities with access to safe, stable housing

- Communities where families have access to high-quality preschool

- Communities where families have access to nurturing and safe childcare

- Communities where families have access to safe, engaging after-school programs and activities

- Communities where families have access to medical care and mental health services

- Communities where families have access to economic and financial help

- Communities where adults have work opportunities with family-friendly policies

Preventing Maltreatment in Early Childhood Education Programs [22]

Levels of Prevention

Prevention programs are commonly categorized as primary, secondary or tertiary prevention programs. All of these levels are important components of a continuum of support for families and contribute to the prevention of child maltreatment. In order to meet the full range of needs of families, including those at risk, communities have the greatest success when they approach prevention on all of these levels.

Primary Prevention is defined as programs and services that provide families with the support that they need to build protective factors and prevent the development of risk factors and vulnerabilities. By supporting parents and caregivers, these programs and services help to ensure that children have stable and healthy living environments in which to grow and develop. These are typically non-targeted programs and services that may be accessed by all families with no screening requirements. Through engagement with families, programs can identify areas where additional support may be required. Primary Prevention programs include early childhood development and parenting programs such as those available in Parent Link Centres, which offer programs such as the Triple P – Positive Parenting Program to provide information, resources, and support to parents.

Secondary Prevention – Early Intervention is defined as involvement with families when vulnerabilities are first identified to strengthen protective factors, reduce the impact of risk factors, and reduce the need for more intrusive and intensive interventions. Families served in these programs usually have one or more identified risk factors, such as poverty, parental substance abuse, young parental age, parental mental health issues such as depression, parental or child disabilities, or exposure to family violence. Early Intervention programs include Home Visitation programs that provide services to expecting and new mothers who are experiencing one or more risk factors, and Head Start Programs which serve children from low-income families.

Tertiary Prevention – Intervention or Treatment is defined as targeted interventions for children and families after maltreatment has occurred, to reduce the negative consequences of maltreatment and to prevent its recurrence. Within Human Services, tertiary prevention is provided under Child Intervention Services and may include intensive in-home family support services.

Principles of Effective Prevention Programs [23]

Effective prevention and early Intervention programs must be:

- Family-centred: Based on a respectful, strengths-based approach that views the family as central to the child’s well-being.

- Proactive: Strive to promote family wellness in families that have not experienced child maltreatment. Proactive programs are based on new information about

development, providing more social interaction and parental support, and an emphasis on the reinforcement of positive behaviours. - Theory-Driven: Have a scientific justification or logical rationale; describe a strategy of how or why the strategy is likely to change behaviour.

- Evidence-based: Have empirical research supporting their efficacy.

- Comprehensive: Include multiple components and affect multiple settings to address a wide range of risk and protective factors of the target population.

- Culturally Appropriate: Tailored to fit within the cultural beliefs and practices of specific groups.

Services for Indigenous Families[24]

Statistics indicate that the number of Indigenous children coming into care has continued to increase and that they continue to be overrepresented in Child Intervention Services. To improve outcomes for Indigenous children, families must have access to culturally appropriate prevention and early intervention programs and services. Effective programs and services recognize and build on strengths in Indigenous families and communities while acknowledging and addressing social-historical factors which impact present-day family life. The following are unique features of Indigenous prevention approaches, as identified in “A Circle of Healing: Family Wellness in IndigenousCommunities.”

- Building strong communities and families through cultural recovery.

- Culture-based healing and prevention which is reflected in service theory, practices, helping roles and relationships, material resources and staff training.

- Adopting the family unit as the main focus in understanding matters of children’s maltreatment and wellness, and also placing emphasis on social network, community, and public policy influences.

- Focusing on creating strengths and building resourcefulness in addition to healing and protection.

- Mobilizing informal support systems, extended family, friends, and neighbours, to help support families to deal with crisis.

Cultural learning takes place through participation in unique Indigenous programs or agencies; role modelling by cultural teachers and volunteers; traditional ceremonial or spiritual practices, exposure to Indigenous materials, cultural items and images; culturally unique forms of relationships such as talking circles, healing practices and medicines; and natural exploration and reinforcement of learnings.

“A Circle of Healing” also notes that child and family well-being in urban Indigenous communities presents special challenges, related in large part to the migration experience itself. Families move from small, rural homogeneous communities to large urban environments where the indigenous community is dispersed. Indigenous family services in urban areas seek to build community relationships and help break down social isolation. This is related to cultural recovery and the adaptation of traditional values

and norms of an urban environment.

Physical and Behavioural Signs of Child Maltreatment

It is important to recognize high-risk situations and the signs and symptoms of maltreatment. If you suspect a child is being harmed or the child directly discloses that they have experienced abuse or neglect, reporting suspicions may protect him or her and help the family receive assistance. Any concerned person can report suspicions of child abuse or neglect.

Reporting your concerns is not making an accusation; rather, it is a request for an investigation and assessment to determine if help is needed.

Common Signs of Maltreatment:

Child

- They are no longer interested in activities they used to like

- Changes in behaviour, e.g., more aggressive or hyperactive

- Going backwards in development, e.g., not being able to use the potty when they have already been potty trained

- Developing new and unusual fears

- Lack of parental supervision

- Lack of parental attention

- Unexplained injuries, such as bruises, fractures, or burns. NOTE: Young babies are not able to injure themselves until they begin to move

- Injuries that don’t match the explanation given by the parent or child

- Untreated medical or dental problems

- Sexual behaviour or knowledge that is inappropriate for the child’s age

- Trouble walking or sitting, or pain in the groin area

- Child acts out abuse they have experienced and may abuse other children

- Frequent headaches or stomach aches

- Seeking a stranger’s affection

- Poor growth or weight gain

- Poor hygiene

- Lack of clothing or supplies

Adult:

You can also look at the adult’s behaviour for indications of child maltreatment. It is important to pay attention to other behaviours that may seem unusual or concerning.

- Denies the existence of—or blames the child for—the child’s problems in school or at home

- Asks teachers or other caregivers to use harsh physical discipline if the child misbehaves

- Sees the child as entirely bad, worthless, or burdensome

- Demands a level of physical or academic performance the child cannot achieve

- Looks primarily to the child for care, attention, and satisfaction of the parent’s emotional needs

- Shows little concern for the child

It is important to pay attention to other behaviours that may seem unusual or concerning. Additionally, the presence of these signs does not necessarily mean that a child is being maltreated; there may be other causes. They are, however, indicators that others should be concerned about the child’s welfare, particularly when multiple signs are present or they occur repeatedly.

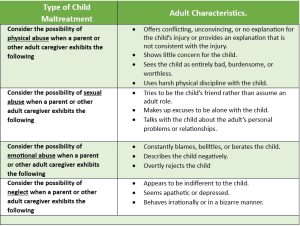

Signs of Maltreatment Related to Specific Types of Abuse

Table 6.2 – Signs of Physical Abuse[25]

| Scenario | Characteristics |

| A child who exhibits the following signs may be a victim of physical abuse: | · Has unexplained injuries, such as burns, bites, bruises, broken bones, or black eyes

· Has fading bruises or other noticeable marks after an absence from school · Seems scared, anxious, depressed, withdrawn, or aggressive · Seems frightened of his or her parents/caregivers and protests or cries when it is time to go home · Shrinks at the approach of adults · Shows changes in eating and sleeping habits · Reports injury by a parent or another adult caregiver · Abuses animals or pets |

| Consider the possibility of physical abuse when a parent or other adult caregiver exhibits the following | · Offers conflicting, unconvincing, or no explanation for the child’s injury or provides an explanation that is not consistent with the injury

· Shows little concern for the child · Sees the child as entirely bad, burdensome, or worthless · Uses harsh physical discipline with the child · Has a history of abusing animals or pets

|

Table 6.3 – Signs of Sexual Abuse[27]

| Scenario | Characteristics |

| A child who exhibits the following signs may be a victim of sexual abuse: | · Has difficulty walking or sitting

· Experiences bleeding, bruising, or swelling in their private parts · Suddenly refuses to go to school · Reports nightmares or bedwetting · Experiences a sudden change in appetite · Demonstrates bizarre, sophisticated, or unusual sexual knowledge or behaviour · Reports sexual abuse by a parent or another adult caregiver · Attaches very quickly to strangers or new adults in their environment |

| Consider the possibility of sexual abuse when a parent or other adult caregiver exhibits the following | · Tries to be the child’s friend rather than assume an adult role

· Makes up excuses to be alone with the child · Talks with the child about the adult’s personal problems or relationships |

Table 6.4 – Signs of Emotional Abuse[28]

| Scenario | Characteristics |

| A child who exhibits the following signs may be a victim of emotional abuse: | · Shows extremes in behavior, such as being overly compliant or demanding, extremely passive, or aggressive

· Is either inappropriately adult (e.g., parenting other children) or inappropriately infantile (e.g., frequently rocking or head-banging) · Is delayed in physical or emotional development · Shows signs of depression or suicidal thoughts · Reports an inability to develop emotional bonds with others |

| Consider the possibility of emotional abuse when a parent or other adult caregiver exhibits the following | · Constantly blames, belittles, or berates the child

· Describes the child negatively · Overtly rejects the child |

Table 6.5 – Signs of Neglect[29]

| Scenario | Characteristics |

| A child who exhibits the following signs may be a victim of neglect: | · Is frequently absent from school

· Begs or steals food or money · Lacks needed medical care (including immunizations), dental care, or glasses · Is consistently dirty and has severe body odor · Lacks sufficient clothing for the weather · Abuses alcohol or other drugs · States that there is no one at home to provide care |

| Consider the possibility of neglect when a parent or other adult caregiver exhibits the following | · Appears to be indifferent to the child

· Seems apathetic or depressed · Behaves irrationally or in a bizarre manner · Abuses alcohol or other drugs |

Understanding the Cause of Child Maltreatment[30]

Different models and theories try to help us understand the causes of child abuse and, therefore, how to prevent it. There isn’t one theory that is the best or explains it all. Rimer and Prager (2016) discuss a combination of the following can help us understand what increases the risk and cause of child abuse:

- a caregiver’s potential to abuse, such as an abusive upbringing;

- the caregiver’s view of their child perhaps as difficult to care for, increasing risk;

- situations in the environment, such as low finances, and social situations, like domestic abuse.

This resource focuses mainly on Steele’s model of understanding abuse. Steele’s model considers how both the caregiver, their view of the child and the stressors play a role in abuse occurring but also how the absence or lack of engagement in supports impacts whether abuse actually occurs or not.

The more we can understand why child abuse happens, the better we are able to consider the possibilities to prevent child abuse.

Understanding risk

- Caregiver’s potential to abuse

- Caregiver’s view of the child

- Environmental and social factors (Rimer & Prager, 2016)

Background

Dr. Brandt F. Steele was an early pioneer in the research on understanding child abuse and neglect. He and Dr. C. Henry Kempe became the first to identify physical and psychological symptoms (signs) of child abuse by parents. Their work became one of the most important medical contributions to the Journal of the American Medical Association of the twentieth century (Brandt F Steele, 2005).

Steele’s work focused on figuring out why parents would abuse their children and what could be done to stop it. He was the first to document that people who abuse children were often abused or neglected as children themselves (Korbin & Krugman, 1987).

Steele’s key to his success was his belief that “if you don’t understand someone’s behaviour, you don’t have enough history.” He had infinite patience and compassion for all those who were abused—including all those who were now abusers. He believed in the efficacy of mental health treatment and multidisciplinary approaches to recognition and treatment. Child psychiatrist Ruth Kempe, the widow of Dr. Henry Kempe, also worked closely with Steele. Ruth Kempe said: “It was extremely fortunate for the field that Steele was the psychiatrist that began to see the parents and evaluate the families. Steele was able to see them not as traditional psychiatric patients but simply as distressed people who often, because of their own childhood history, had a particularly difficult problem with parenting. This approach enabled Henry Kempe and Steele to provide treatment programs that addressed the parents as much as the children. He knew that these parents were not villains and that they loved their children, they just didn’t know how to love them well” (Korbin & Krugman, 1987).

Steele developed a psycho-social model to:

- Understand the causes of abuse in a family situation

- Determine the risk of abuse

- Prevent further abuse

The model is consistently helpful today as we look at what went wrong and what we can do to support families to help prevent future child abuse and neglect.

Psycho-Social Model

The Psycho-Social model is a clinical theory with a focus on physical abuse, although it can help us understand other types of abuse. The model helps us learn about why the abuse happened (causes), which helps us understand and address the risk of further abuse.

Physical abuse to a child is different than a single incident of assault between two adults. When physical abuse occurs, there are dynamics within the family; there is a relationship between the child and the abuser. Police can’t just criminally charge and remove the perpetrator from the home and then legally consequence them as they would in other physical assault cases. As parents of the child, they will continue a relationship with the child and likely return to the home – which will again pose risk to the child if the dynamics of the physical abuse are not addressed. In stranger physical assault, the perpetrator can be released on condition not to associate with the victim.

One can’t just consider the incident that occurred in isolation but rather with other factors.

Do elements exist to suggest:

- the dynamics of abuse are present, and

- there is the risk the child will be harmed again.

Steele’s, Psycho-Social Model is a relevant framework when considering factors causing neglect. However, it is less likely that a neglectful parent will selectively neglect a child or a couple of children over others. In situations of neglect, the low quality of care provided by the parent to ALL the children is more consistent. Unlike physical abuse, where one child can be targeted over others in a family.

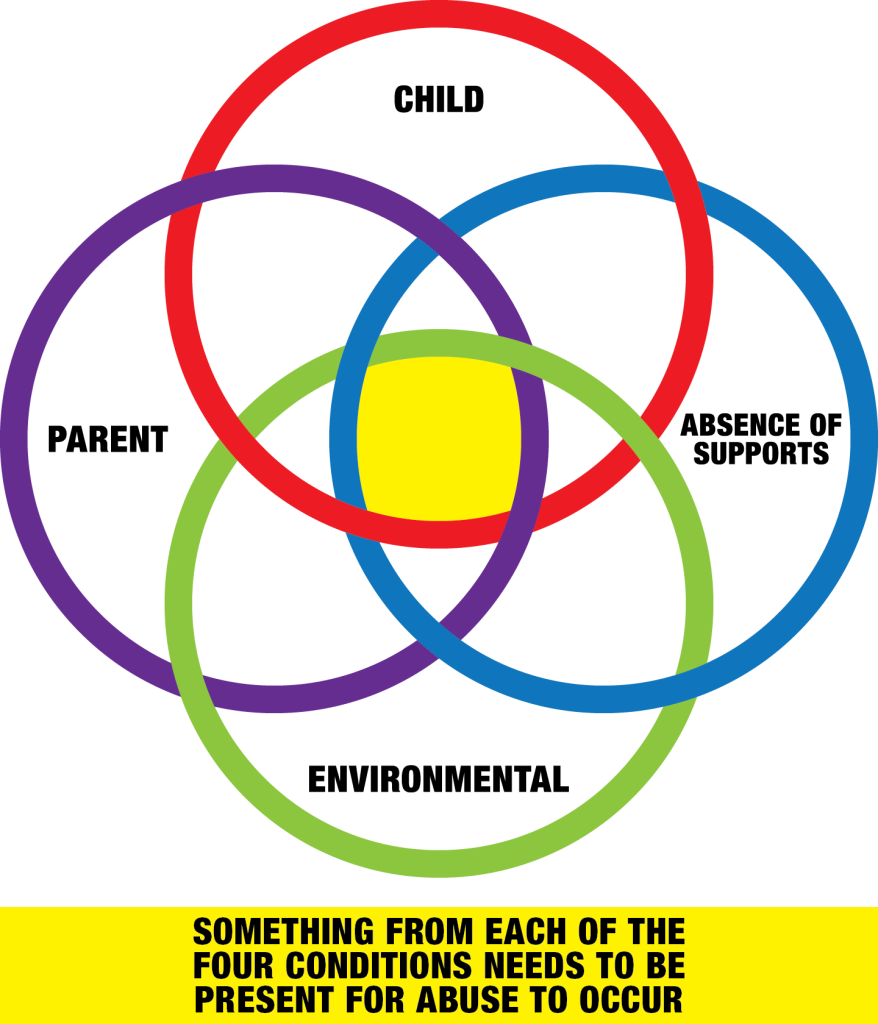

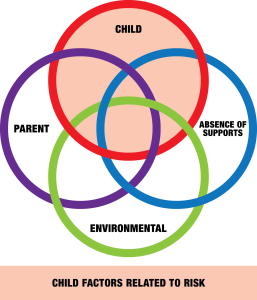

In determining whether an injury is the result of physical abuse, we consider Steele’s, Psycho-Social Model. The model identifies that maltreatment of children (abuse and/or neglect) can be attributed to the convergence of specific factors, and these factors, when combined, cause (contribute to) children being abused.

Steele identified the four conditions which are almost always present that played a role, when combined, caused (contributed to) children being abused.

- Parent factors related to risk

- Child factors related to risk

- Environmental factors related to risk

- The absence of supports, increasing risk

Steele theorizes that the child is abused due to several factors connected to each other and not in isolation. We know there is a person who abuses the child and a child who is the victim of abuse. Steele considered the dynamics within that relationship, the members of the family, what was happening in their home and around them and the support(s) available, and if so, were they willing to access it? When we take each of these in isolation, one cannot predict the risk of abuse. When Steele considered the factors that were going on together, the risk of abuse became apparent.

For example, a caregiver may have experienced childhood abuse and have low frustration tolerance (Parent Factors). They have a child who with diagnosed with social anxiety disorder and struggles to attend school, is clingy with the parent, and is demanding of the parent’s time resources (Child Factors). The school attendance counsellor keeps leaving voice messages and sending emails to the parent about the child’s absences, threatening to refer to the Children’s Aid Society due to a lack of follow-through to get help for the child and get the child to attend school. The parent keeps missing work due to the child’s anxiety impacting the finances and ability to provide for the family (Environmental Factors). The parent has not accessed counselling for the child recommended by the School Attendance Counsellor (Absence of Supports). The convergence of all these factors combined increases the risk of child abuse. Not one factor alone, not one area alone, but all the areas coming together create a significant risk of child abuse, not unlike an erupting volcano. If we don’t look at all things going on together, we miss important information to assess risk, support the family, and help prevent abuse or further abuse if it hasn’t already happened.

Considering the scenario above, if one of the areas does not have any factors related to risk, then the risk of abuse is lowered significantly. For example, the caregiver may have a childhood history of abuse and difficulty coping or low-frustration tolerance (Parent factors). The child may struggle with social anxiety, is needy and draining at times, and misses school (Child Factor). There may be stressors in the environment, such as low finances due to absences from work due to caring for the child (Environmental Factors). There is the extended family who helps care for the child, providing much-needed relief. They loan (give) the family money when needed. More importantly, the caregiver is willing to access support from the extended family. While Absence of Supports is about support not being available, more than that, Absence of Support is about an individual’s willingness to seek out and access support when needed. In the example above, the parent factors are significant, including the child and environmental factors; however, the supports are in place, and the parent’s willingness to access the supports reduces the risk of abuse significantly.

we will discuss factors that contribute to risk starting with parent factors related to risk in the following section.

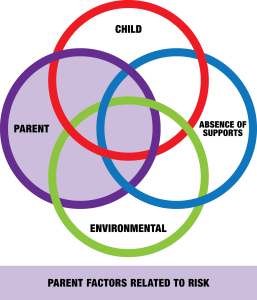

Parent Factors Related to Risk of Abuse:

Psycho-Social Model

- Parent factors related to risk

- Child factors related to risk

- Environmental factors related to risk

- The absence of support increasing risk

Something from each of the four conditions needs to be present to cause a child to be abused.

The parent must have the predisposition to abuse their children.

They often experienced maltreatment in their own childhood.

They often have low self-esteem, feel unloved and uncared for, which affects all areas of their life, and relationships, including how confident and competent they are in parenting.

They lack trust in other people and will emotionally isolate themselves to avoid pain. This causes conflict in their relationships where outside sources of support and help are not available.

Parents who maltreat their children are often preoccupied with trying to find ways to get their own emotional needs met, and they often expect their children to meet those needs.

Abusive parents may look to their children to validate their self-esteem. They attribute the child’s behaviour as a rejection toward them rather than appropriately seeing it as natural behaviour related to the child’s age and stage of development.

Many (abusive parents) have poor emotional control, where they are volatile and prone to emotional outbursts.

They have unrealistic expectations of their children’s behaviour, increasing the likelihood of less understanding or patience with the child and perhaps being more punitive.

Both abusive and neglectful parents may exhibit a serious lack of empathy for their children (and a lack of understanding of their children’s developmental needs) where they mechanically perform caregiving without any warmth, sensitivity, or empathetic action (in response to the perceived needs of the child).

Some parents who have been raised with violence assume that violence is “natural.”

Both abuse and neglect may occur in families in which parents are mentally ill, developmentally challenged, or emotionally disturbed (however, the percentage of abusive or neglectful parents with disorders of this type is relatively small).

There is something in the parent’s life that has contributed to the caregiver’s predisposition to abuse the child.

Child Factors Related to Risk of Abuse:

Psycho-Social Model

- Parent factors related to risk

- Child factors related to risk

- Environmental factors related to risk

- The absence of support increasing risk

Something from each of the four conditions needs to be present to cause a child to be abused.

Children who are perceived by their parents as different, abnormal, defective, or lacking in comparison to other children, are more likely to be victims of child maltreatment.

Child factors are not about a child’s wrongdoings and they are not about making children responsible for the abuse they experience due to their behaviour or event. Children are NEVER responsible for the abuse and NEVER deserve to be abused. The child’s condition or situation is about identifying the factors that increase the risk of abuse for children, particularly how the parent perceives the child in the situation. These factors include:

The parent believes that the child’s role is to behave and respond in ways to please and satisfy the parent;

Children are more prone to abuse if they cannot meet the parent’s expectations for “good” or “right” behaviour;

Some children are more difficult to care for due to their personality and temperament. This puts a child at a greater risk of being abused;

Children are at higher risk of abuse and neglect if they have a cognitive disability, mental health issues, conduct issues, learning disability, physical disability, hyperactive, premature, or chronic illnesses or medical conditions. These children often need continuous care, supervision and attention, which places excessive demands on their parents and increases the risk of abuse.

While abuse is possible for all children in a family, it is typical to find one child the target of most of the abuse. Children are at higher risk of maltreatment during specific developmental periods, e.g., infants requiring constant care or due to frequent crying and the toilet training stage, where there are power struggles and conflicts.

Characteristics of the child that the caregiver feels are difficult or different make them more challenging to care for, such as premature birth, birth trauma, unplanned, unwanted pregnancy, unsuccessful breastfeeding, adoption fantasy, foster-to-adopt dream, and step-child. The caregiver’s idea of what they thought was supposed to happen didn’t, and they struggled to bond with the baby increasing the risk of abuse.

The child is unwanted or does not meet the parent’s expectations; therefore, any behaviour the child exhibits is seen as out of the ordinary and perceived as demanding, challenging and a problem.

There is something about the child that the caregiver perceives as difficult or problematic, increasing the risk of abuse.

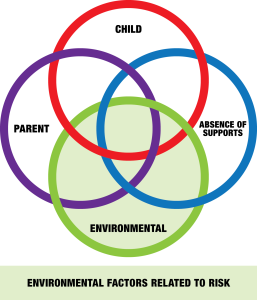

Environmental Factors Related to Risk of Abuse:

Psycho-Social Model

- Parent factors related to risk

- Child factors related to risk

- Environmental factors related to risk

- The absence of support increases risk

Something from each of the four conditions needs to be present to cause a child to be abused.

The precipitation of an abusive event is often related to excessive stress or a family crisis.

The parent may have difficulty dealing with stress due to poor coping skills (and low self-esteem).

There may be a significantly stressful event causing increased risk to children.

Unmanageable stress is often the “trigger” that precipitates an abusive event.

The size of the trigger depends on the number of parent and child factors contributing to the risk of abuse. If the parent has a large predisposition to abuse due to a significant number of factors along with numerous child factors, a small stressor can set off an abusive event. For example: running out of milk. The opposite is true if there are a few factors contributing to a predisposition. A large stressor is needed to trigger an abusive event.

High levels of chronic family stress may also contribute to neglect. For example, two years of COVID contributed to job loss, child homeschooling, financial loss, isolation and so on.

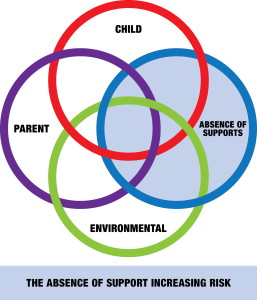

Absence of Support Increasing Risk of Abuse:

Psycho-Social Model

- Parent factors related to risk

- Child factors related to risk

- Environmental factors related to risk

- The absence of support increases risk

Something from each of the four conditions needs to be present to cause a child to be abused.

The unavailability of support and resources, or a family’s reluctance to access or utilize them, contributes greatly to maltreatment.

There are numerous reasons why a caregiver does not access support and resources, increasing risk. This can include a lack of availability and services, such as a remote northern community where counselling supports are hours away. Or cultural norms that one is not to share personal information outside of the family. This blocks a caregiver from accessing help. Supports and resources include agencies, institutions, organizations, community centres, child-care centres, schools, health care, mental health care and support, physical health care, and religious support, among support from family, friends, neighbours and community members. The ability to seek out and access support in the face of adversity is a protective factor to prevent and reduce the risk of child abuse. The lack of access, the lack of availability or the unwillingness to access support and resources in the raising of children, being in a relationship, coping and managing with life, work, family, extended family, work, finances and so on is a risk factor for child abuse. This can include:

Parents who are unwilling to reach out to other people for help, fear others or have an attitude it is “nobody’s business” cause isolation which prevents families from accessing support when needing help in coping with stressful situations.

Family conflict can impact a caregiver’s ability to seek support from extended family to help with child care, among other things increasing the risk of abuse due to conflict and lack of support.

Long waiting lists for helping resources that are affordable dissuade users from seeking support in the first place.

Accessibility of resources plays a role in whether people reach out to access them. For example, a community centre within walking distance from one’s home compared to one that requires a bus ride that is timely and costly.

Resources that are culturally specific, in the language of the end user’s preference, can play a role in whether someone reaches out to access support or not.

Cultural norms to not share personal problems outside the family home may prevent caregivers from reaching out for support.

Lack of trust and confidentiality in one’s community can prevent a caregiver from reaching out for help and support.

Intergenerational trauma may prevent a caregiver from reaching out for support to organizations in perceived positions of authority due to past and historical trauma.

Lack of knowledge of available supports may prevent a caregiver from accessing help such as a women’s shelter, increasing the risk of abuse.

Language barriers may prevent a caregiver from accessing knowledge about available resources.

The myth of self-sufficiency that a caregiver should be able to raise their children on their own. They had the child; they should have an innate understanding of what children need and be able to provide and manage those needs. “You’re a mom, you should know.” Holding on to these beliefs can prevent a caregiver from reaching out for support, increasing the risk of abuse.

Racism can prevent a caregiver from reaching out for support. Racism is a barrier to accessing support when a caregiver experiences judgment, and hostility, is not believed or is even turned away. These real-life experiences become the fabric of the community preventing people of diverse cultural backgrounds to reach out for help.

Absence of Supports

Absence of Supports increases the risk of abuse. No access to supports during the global pandemic increased the risk of abuse.

The global pandemic closed all access to resources and supports which increased the risk of child abuse. Parks were taped off, children were not allowed outside, physical schools were closed, recreation facilities were closed, sports activities were stopped, and children began online education in unprecedented isolation. Support and resources for families were not available.

One’s sexual orientation can prevent someone from reaching out for support. The belief that they will not be safe or respected is a profound motivator to keep what is happening private and prevents a 2SLGBTQIA+ person from reaching out for help, or a transgender person seeking support when they feel they will be judged and unsafe, so they don’t try. Both of these scenarios increase the risk of abuse.

One’s personal religion or religious affiliation may prevent caregivers from seeking support outside of the church. If the circumstances don’t change within the family and the support from the church does not help, the risk of abuse increases. The church can be helpful in some situations. It can be harmful if the right kind of support is not offered.

Fear of the Children’s Aid Society can prevent a caregiver from reaching out to access support. Someone who recognizes that they need help, perhaps things have gone too far, may feel overwhelmed with fear that their children will be taken away. This prevents the caregiver from accessing support, increasing the risk of abuse.

A lack of knowledge and understanding about the role of the Children’s Aid Society (CAS) prevents the caregiver from reaching out for help. The caregiver believes that CAS would apprehend their children if they knew what is happening in the child’s life. When in fact, the CAS’s primary purpose is to promote the well-being and best interests of the child, including protection. In most situations, this means leaving the children with their caregiver and assisting the caregiver to be a better parent.

Lack of community investment in infrastructure to support families and children. Without the needed recreational places for families and children, such as parks and playground equipment, community centres, ice rinks, swimming pools, basketball courts, low and no-cost children’s activities, risk of child abuse increases.

When assessing for risk of abuse, apply Steele’s Psycho-Social theory by identifying all the parent factors supported with evidence that contribute to the risk of child abuse. Then identify all the child factors supported with evidence that increase the risk of the child being abused. With the environmental factors, identify all the stressors in the family, supported with evidence of increasing the risk of abuse. Last, identify what resources the caregiver has accessed or not. Where possible, label the caregiver’s thoughts, feelings, and attitude toward help and support.

Pause to Reflect

| Think back to your example situations. What signs might a teacher or caregiver notice for each of these? |

Preventative Strategies

Child abuse and neglect are serious problems that can have lasting harmful effects on its victims. The goal of preventing child abuse and neglect is to stop this violence from happening in the first place.

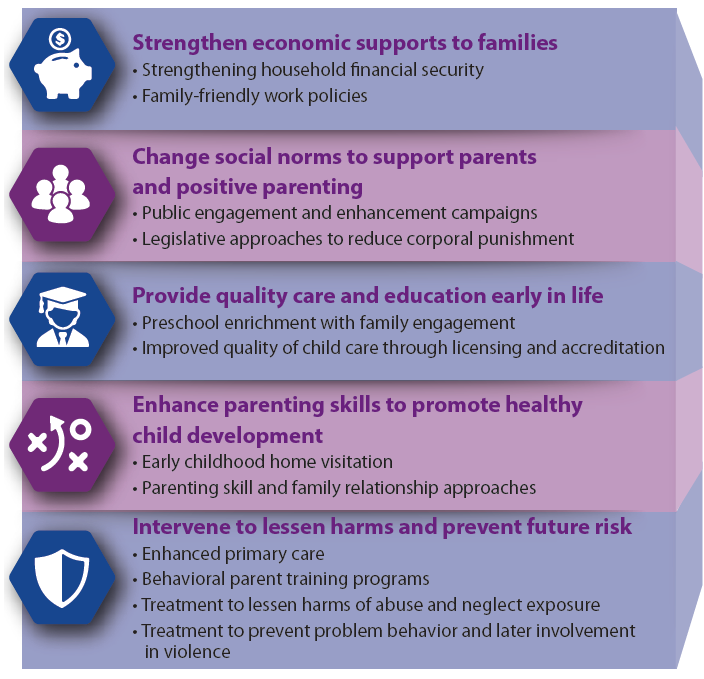

Child abuse and neglect are complex problems rooted in unhealthy relationships and environments. Preventing child abuse and neglect requires addressing factors at all levels of the social ecology–the individual, relational, community, and societal levels.[37] As you can see in Figure 6.5, early care and education has a direct role to play in one of the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention’s strategies and can support families in some of the others. Families who have access to quality childcare, increase the likelihood that children will experience safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments. Access to affordable childcare also reduces parental stress and maternal depression, which are risk factors for child abuse and neglect.[38]

Duty to Report

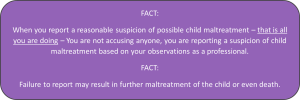

The Child and Family Service Act (section 20) states that “… every person that every person who has reasonable grounds to believe that a child (under the age of 16) needs protection shall report the information to an officer or peace officer” (Government of Saskatchewan, 1996, Sec 12).

The duty to report applies to all regardless of claims of confidentiality. This means that even if your place of work has confidentiality policies in place, the Duty to Report overrides those policies, and you are required to report any suspected child maltreatment.

Duty to Report – Without Delay

Report suspected child maltreatment immediately. Even if you report it to your director, you still have a duty to report it yourself to the authorities. If you know that someone else has reported it you still have a duty to report it immediately.

Ongoing Duty to Report

You also have an ongoing duty to report. If you have made a report and something additional happens or you have additional suspensions then you must report that as well. All incidents must be reported.

Who Do You Report Suspected Child Maltreatment to?

Saskatchewan Social Services -Child Protection Services (CPS) worker.

contact your nearest 24-hour provincial child protection intake line:

Prince Albert (North) 1-866-719-6164

Saskatoon (Centre) 1-800-274-8297

Regina (South) 1-844-787-3760

First Nations Child and Family Services Agencies

As of 2020, there are 19 delegated Child and Family Services Agencies in Saskatchewan providing Child Protection and Prevention Services for First Nations Communities. Click on the image to the left to see contact information for each location.

RCMP

There are 113 RCMP detachments in the province of Saskatchewan. Click on the image to view the contact information for each.

Local Police

What to Include When You Report Suspected Child Maltreatment

When you report you should include the following [40]:

- Your name, telephone number and relationship to the child (This information remains confidential, and may be provided anonymously; unless your testimony is required in a court proceeding);

- Your immediate concerns about the child’s safety;

- The child’s location;

- The child’s name;

- The child’s age and gender;

- information about the situation including your observations or, disclosures made to you;

- Information about the family, caregivers and alleged abuser;

- Other children who may be at risk because of the situation; and

- Any other relevant information.

Rights to Confidentiality and Immunity

Mandated reporters are required to give their names when making a report. However, the reporter’s identity is kept confidential. Reports of suspected child abuse are also confidential. Mandated reporters have immunity from state criminal or civil liability for reporting as required. This is true even if the mandated reporter acquired the knowledge, or suspicion of abuse or neglect, outside his/her professional capacity or scope of employment.

Consequences of Failing to Report

A person who fails to make a required report is guilty of a misdemeanour.

After the Report is Made

After a report is made the Child Protection Services (CPS) and the local police are responsible for conducting an investigation.

CPS will determine if there are grounds that the child requires protection, whereas the police will investigate to determine if there has been a criminal offence, under the Criminal Code of Canada, that would require changes to be laid.

As an educator, your role after a report is made is to support the child during and after the investigations and to provide follow-up services and information to the professionals involved. [42]

The Impact of Childhood Trauma on Well-Being

|

Child abuse and neglect can have lifelong implications for victims, including on their wellbeing. While the physical wounds may heal, there are many long-term consequences of experiencing the trauma of abuse or neglect. A child or youth’s ability to cope and thrive after trauma is called “resilience.” With help, many of these children can work through and overcome their past experiences.

Children who are maltreated may be at risk of experiencing cognitive delays and emotional difficulties, among other issues, which can affect many aspects of their lives, including their academic outcomes and social skills development (Bick & Nelson, 2016). Experiencing childhood maltreatment also is a risk factor for depression, anxiety, and other psychiatric disorders (FullerThomson, Baird, Dhrodia, & Brennenstuhl, 2016).[43] We will look more closely at this when we examine mental health, social and emotional well-being, adverse childhood events, and trauma-informed care in Chapter 11. |

Working with Children Who Have Been Maltreated

Children who have experienced abuse or neglect need support from caring adults who understand the impact of trauma and how to help. Adverse childhood experiences and trauma-informed care will be addressed more in Chapter 11. Early childhood educators should consider the following suggestions:

- Help children feel safe. Support them in expressing and managing intense emotions.

- Help children understand their trauma history and current experiences (for example, by helping them understand that what happened was not their fault, or helping them see how their current emotions might be related to past trauma).

- Assess the impact of trauma on the child, and address any trauma-related challenges in the child’s behavior, development, and relationships.

- Support and promote safe and stable relationships in the child’s life, including supporting the child’s family and caregivers if appropriate. Often parents and caregivers have also experienced trauma.

- Manage your own stress. Providers who have histories of trauma themselves may be at particular risk of experiencing secondary trauma symptoms.

- Refer the child to trauma-informed services, which may be more effective than generic services that do not address trauma.[44]

Summary

Child maltreatment results from the interaction of a number of individual, family, societal, and environmental factors. Child abuse and neglect are not inevitable—safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and environments are key for prevention. Preventing child abuse and neglect can also prevent other forms of violence, as various types of violence are interrelated and share many risk and protective factors, consequences, and effective prevention tactics.[45] When there is suspicion that maltreatment has occurred, it’s critical that early childhood educators report that. And being educated on trauma-informed care can help you support children who have been the victims of child maltreatment.

Resources for Further Exploration

· What is Child Abuse and Neglect?

· Children’s Bureau’s Office on Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention Guide

· Resource Guide for Mandated Reporters

· National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome

· American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children

References

- Child and Family Services Act (2023). https://publications.saskatchewan.ca/#/products/460 ↵

- Healthy Foundations in Early Childhood Education, Pimento & Kernested, Child Maltreatment) ↵

- Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect: Final Report, Health Canada, Nico Trocme et. al., In the public domain ↵

- What are child abuse and neglect? by CDC is in the public domain. ↵

- Imaging of Abusive Head Trauma: A Radiologist's Perspective, by Jung-Eun Cheon & Ji Hye Kim, Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society, open access ↵

- Imaging of Abusive Head Trauma: A Radiologist's Perspective, by Jung-Eun Cheon & Ji Hye Kim, Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society, open access ↵

- Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma (Shaken Baby Syndrome, Saskatchewan Prevention Insitute, ↵

- Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma (Shaken Baby Syndrome, Saskatchewan Prevention Insitute, ↵

- Female genital mutilation, by the WHO, CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- Child Sexual Abuse - It is your Business, Canadian Centre for Child Protection ↵

- Child Sexual Abuse - It is your Business, Canadian Centre for Child Protection ↵

- Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect 2008, Public Health Agency of Canada, Canadian Child Welfare Research Portal, in the public domain ↵

- What is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing the Signs and Symptoms by the Children’s Bureau is in the public domain. ↵

- Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect 2008, Public Health Agency of Canada, Canadian Child Welfare Research Portal, in the public domain ↵

- Incident-based Crime Reporting Survey, Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, in the public domain ↵

- Incident-based Crime Reporting Survey, Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, in the public domain ↵

- Prevention and Early Intervention Framework for Children, Youth and Families, by Alberta Government, is used with permission ↵

- Prevention and Early Intervention Framework for Children, Youth and Families, by Alberta Government, is used with permission ↵

- Alberta Government. (2019). Well-Being and Resiliency: A Framework for Supporting Safe and Healthy Children and Families. Retrieved from https://open.alberta.ca/publications/9781460141939 ↵

- Risk and Protective Factors by the CDC is in the public domain. ↵

- Risk and Protective Factors by the CDC is in the public domain. ↵

- Prevention and Early Intervention Framework for Children, Youth and Families, by Alberta Government, is used with permission ↵

- Prevention and Early Intervention Framework for Children, Youth and Families, by Alberta Government, is used with permission ↵

- Prevention and Early Intervention Framework for Children, Youth and Families, by Alberta Government, is used with permission ↵

- What is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing the Signs and Symptoms by the Children’s Bureau is in the public domain. ↵

- More than meets the eye by Airman 1st Class Jessica H. Smith is in the public domain. ↵

- What is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing the Signs and Symptoms by the Children’s Bureau is in the public domain. ↵

- What is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing the Signs and Symptoms by the Children’s Bureau is in the public domain. ↵

- What is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing the Signs and Symptoms by the Children’s Bureau is in the public domain. ↵

- Determing the Cause of Child Abuse, by Susan Loosley & Jen Johnson, Child Maltreatment: An Introductory Guide with Case Studies, is licenced by CC BY NC SA ↵

- Brandt Steel Model by Fanshawe College, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- Psycho-Social Model, Steele, B. – Parent Factors Related to Risk by Fanshawe College, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- Psycho-social Model, Steele, B. – Child Factors Related to Risk by Fanshawe College, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- Psycho-social Model, Steele, B. – Environmental Factors Related to Risk by Fanshawe College, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- Psycho-social Model, Steele, B. – Absence of Support Increasing Risk by Fanshawe College, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- covid virus by CDC, Unsplash License ↵

- Prevention Strategies by the CDC is in the public domain. ↵

- Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Leveraging the Best Available Evidence by the CDC is in the public domain. ↵

- What are child abuse and neglect? by the CDC is in the public domain. ↵

- 2019 Provincial Child Abuse Protocol, by the Government of Saskatchewan, Saskatchewan.ca, is used with permission ↵

- Image by Petr Kratochvil is in the public domain. ↵

- 2019 Saskatchewan Child Abuse Protocol, by the Government of Saskatchewan, used with permission ↵

- What is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing the Signs and Symptoms by the Children’s Bureau is in the public domain. ↵

- 2018 Prevention Resource Guide by the Administration for Children and Families is in the public domain. ↵

- What are child abuse and neglect? by the CDC is in the public domain. ↵