12

INTRODUCTION

Saving to build wealth is investing. When people have too much money to spend immediately—that is, a surplus of disposable income—they become savers or investors. They transfer their surplus to individuals, companies, or governments that have a shortage or too little money to meet immediate needs. This is almost always done through an intermediary—a bank or broker—who can match up the surpluses and the shortages. If the capital markets work well, those who need money can get it, and those who can defer their need can try to profit from that. When you invest, you are transferring capital to those who need it on the assumption that they will be able to return your capital when you need or want it and that they will also pay you for its use in the meantime.

Investing happens over your lifetime. In your early adult years, you typically have little surplus to invest. Your first investments are in your home (although primarily financed with the debt of your mortgage) and then perhaps in planning for children’s education or for your retirement.

After a period of just paying the bills, making the mortgage, and trying to put something away for retirement, you may have the chance to accumulate wealth. Your income increases as your career progresses. You have fewer dependents (as children leave home), so your expenses decrease. You begin to think about your investment options. You have already been investing—in your home and retirement—but those investments have been prescribed by their specific goals.

You may reach this stage earlier or later in your life, but at some point, you begin to think beyond your immediate situation and look to increase your real wealth to ensure your future financial health. Investing is about that future.

Investment also goes beyond simply contributing one’s own individual wealth and financial health. The investments we make can contribute to the growth of businesses, organizations, and communities. The investment choices we make can have a significant economic and social impact in the world.

With regard to Indigenous communities in Canada, economic growth is fueled by investment. According to Chief Michael LeBourdais of the Whispering Pine/Clinton Indian Band, “investment can be generated from local residents through savings, through home equity or from outside sources. In Canada, private sector investment outweighs public sector investment by five to one. Three times as many jobs are created in the private sector as in the public sector” (Tulo Centre of Indigenous Economics, 2014, p. 6). Thus, attracting private investment to Indigenous business and economic development projects is an important part of economic growth. Many Indigenous entrepreneurs lack access to capital and rely heavily on personal and family support to help finance their businesses; “there is a growing need for ‘angel investors’ ” as well as other private investment options (Cooper, 2016). Furthermore, “investment creates jobs and business opportunities. This, in turn, builds the fiscal capacity of governments to support social improvements and build infrastructure. It also encourages a natural constituency for accountable, fiscally responsible government as the investment climate is enhanced. Indigenous governments must participate in federations and market systems to provide fiscal and economic opportunities for their governments and members” (Tulo Centre of Indigenous Economics, 2014, p. 7). Therefore, investing can help to increase your individual financial well-being, as well as the economic and social well-being of communities throughout the country.

Through the creation of the First Nations Fiscal and Statistical Management Act on March 23, 2005, the First Nations Finance Authority (FNFA), the First Nations Financial Management Board (FNFMB), and the First Nations Tax Commission (FNTC) were established. Canada’s First Nations and the Government of Canada worked together to support the creation of these new institutions in order to assist First Nations to better access capital markets and more investment opportunities. The FNFMB helps First Nations to build stronger community management and accountability frameworks, including best practices, standard-setting, and capacity-building, that enhance First Nations’ ability to participate in raising capital through the FNFA (Cooper, 2016). The FNTC, as mentioned in Chapter 6, helps First Nations use their property tax revenue to secure long-term borrowing and oversee the bylaw approval process, which provides greater investor certainty. As Cooper states, “the ability to successfully provide transparent, risk-related investment opportunities to private capital providers requires that First Nation communities undertake initiatives to enhance their ability to borrow. The practices and processes of the FNFA and the FNFMB are tools which can be of immediate assistance to the First Nations communities as they proceed to prepare themselves for dealing with private capital providers” (Cooper, 2016, p. 172).

How should you invest your money? This is a critical question that we must all ask ourselves as we reach that stage of our lives when we are ready to begin investing. Today, there are more and more options available to investors who wish to invest their money in socially responsible businesses. Furthermore, many businesses are focusing more on corporate social responsibility (CSR), which is focused on economic, social, and environmentally sustainable activities—and not only because they know it is the right thing to do, but also because it is good business. More and more companies are sharing their CSR record, which makes it easier for investors to research and make informed decisions.

12.1 INVESTMENTS AND MARKETS: A BRIEF OVERVIEW

Learning Objectives

- Identify the features and uses of issuing, owning, and trading bonds.

- Identify the uses of issuing, owning, and trading stocks.

- Identify the features and uses of issuing, owning, and trading commodities and derivatives.

- Identify the features and uses of issuing, owning, and trading mutual funds, including exchange-traded funds and index funds.

- Describe the reasons for using different instruments in different markets.

Before looking at investment planning and strategy, it is important to take a closer look at the galaxy of investments and markets where investing takes place. Understanding how markets work, how different investments work, and how different investors can use investments is critical to understanding how to plan your investment goals and strategies.

You have looked at using the money markets to save surplus cash for the short term. By contrast, investing is primarily about using the capital markets to invest surplus cash for the longer term. As in the money markets, when you invest in the capital markets, you are selling liquidity.

The capital markets developed as a way for buyers to buy liquidity (i.e., raise capital). The two primary methods that have evolved into modern times are the bond and stock markets. Both are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 13 “Owning Stocks” and Chapter 14 “Owning Bonds and Investing in Mutual Funds,” but a brief introduction is provided here to give you a basic idea of what they are and how they can be used as investments.

Bonds and Bond Markets

Bonds are debt. The bond issuer borrows by selling a bond, promising the buyer regular interest payments and then repayment of the principal at maturity. If a company wants to borrow, it could just go to one lender and borrow. But if the company wants to borrow a lot, it may be difficult to find any one investor with the capital and the inclination to make that large a loan, taking a large risk on only one borrower. In this case, the company may need to find a lot of lenders who will each lend a little money, and this is done through selling bonds.

A bond is a formal contract to repay borrowed money with interest (often referred to as the coupon) at fixed intervals. Corporations and governments (e.g., federal, provincial, municipal, and foreign) borrow by issuing bonds. The interest rate on the bond may be a fixed interest rate or a floating interest rate that changes as underlying interest rates—rates on debt of comparable companies—change. (Underlying interest rates include the prime rate: the annual interest rate Canada’s major banks and financial institutions use to set interest rates for variable loans and lines of credit, including variable-rate mortgages. The Bank of Canada sets the prime rate.)

Bonds have many features other than the principal and interest; these include the issue price (the price you pay to buy the bond when it is first issued) and the maturity date (when the issuer of the bond has to repay you). Bonds may also be “callable”—that is, redeemable before maturity (paid off early). Bonds may also be issued with various covenants or conditions that the borrower must meet to protect the bondholders (the lenders). For example, the borrower (the bond issuer) may be required to keep a certain level of cash on hand, relative to his or her short-term debts, or may not be allowed to issue more debt until this bond is paid off.

Because of the diversity and flexibility of bond features, the bond markets are not as transparent as the stock markets—that is, the relationship between the bond and its price is harder to determine.

Stocks and Stock Markets

Stocks or equity securities are shares of ownership: when you buy a share of stock, you buy a share of the corporation. The size of your share of the corporation is proportional to the size of your stock holding. Since corporations exist to create profit for the owners, when you buy a share of the corporation, you buy a share of its future profits. You are literally sharing in the fortunes of the company.

Unlike bonds, however, shares do not promise you any returns at all. If the company does create a profit, some of that profit may be paid out to owners as a dividend, usually in cash but sometimes in additional shares of stock. The company may pay no dividend at all, however, in which case the value of your shares should rise as the company’s profits rise. But even if the company is profitable, the value of its shares may not rise, for a variety of reasons having to do more with the markets or the larger economy than with the company itself. Likewise, when you invest in stocks, you share the company’s losses, which may decrease the value of your shares.

Corporations issue shares to raise capital. When shares are issued and traded in a public market such as a stock exchange, the corporation is “publicly traded.” There are many stock exchanges in Canada and around the world. Internationally, the best-known Canadian stock exchange is the Toronto Stock Exchange.

Only members of an exchange may trade on the exchange, so to buy or sell stocks you must go through a broker who is a member of the exchange. Brokers also manage your account and offer varying levels of advice and access to research. Most brokers have web-based trading systems. Some discount brokers offer minimal advice and research along with minimal trading commissions and fees.

Commodities and Derivatives

Commodities are resources or raw materials, including the following:

- agricultural products (food and fibres) such as soybeans, pork bellies, and cotton;

- energy resources such as oil, coal, and natural gas;

- precious metals such as gold, silver, and copper; and

- currencies, such as the dollar, yen, and euro.

Commodity trading was formalized because of the risks inherent in producing commodities—raising and harvesting agricultural products or natural resources—and the resulting volatility of commodity prices. As farming and food production became mechanized and required a larger investment of capital, commodity producers and users wanted a way to reduce volatility by locking in prices over the longer term.

The answer was futures and forward contracts. Futures and forward contracts (or forwards) are a form of derivatives, the term for any financial instrument whose value is derived from the value of another security. For example, suppose it is now July 2018. If you know that you will want to have wheat in May of 2019, you could wait until May 2019 and buy the wheat at the market price, which is unknown in July 2018. Or you could buy it now, paying today’s price, and store the wheat until May 2019. Doing so would remove your future price uncertainty, but you would incur the cost of storing the wheat.

Alternatively, you could buy a futures contract for May 2019 wheat in July 2018. You would be buying May 2019 wheat at a price that is now known to you (as stated in the futures contract), but you will not take delivery of the wheat until May 2019. The value of the futures contract to you is that you are removing the future price uncertainty without incurring any storage costs. In July 2018, the value of a contract to buy May 2019 wheat depends on what the price of wheat actually turns out to be in May 2019.

Forward contracts are traded privately, as a direct deal made between the seller and the buyer, while futures contracts are traded publicly on an exchange such as the Chicago Mercantile Exchange or the New York Mercantile Exchange.

When you buy a forward contract for wheat, for example, you are literally buying future wheat, wheat that doesn’t yet exist. Buying it now, you avoid any uncertainty about the price, which may change. Likewise, by writing a contract to sell future wheat, you lock in a price for your crop or a return for your investment in seed and fertilizer.

Futures and forward contracts proved so successful in shielding against some risk that they are now written for many more types of commodities, such as interest rates and stock market indices. More kinds of derivatives have been created as well, such as options. Options are the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell at a specific price at a specific time in the future. Options are commonly written on shares of stock as well as on stock indices, interest rates, and commodities.

Derivatives such as forwards, futures, and options are used to hedge or protect against an existing risk or to speculate on a future price. For a number of reasons, commodities and derivatives are more risky than investing in stocks and bonds and are not the best choice for most individual investors.

Mutual Funds, Index Funds, and Exchange-Traded Funds

A mutual fund is an investment portfolio consisting of securities that an individual investor can invest in all at once without having to buy each investment individually. The fund thus allows you to own the performance of many investments while actually buying—and paying the transaction cost for buying—only one investment.

Mutual funds have become popular because they can provide diverse investments with a minimum of transaction costs. In theory, they also provide good returns through the performance of professional portfolio managers. Chapter 14 section 4 “Mutual Funds” provides more information on portfolio management fees.

An index fund is a mutual fund designed to mimic the performance of an index, a particular collection of stocks or bonds whose performance is tracked as an indicator of the performance of an entire class or type of security. For example, the Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500 is an index of the five hundred largest publicly traded corporations, and the famous Dow Jones Industrial Average is an index of thirty stocks of major industrial corporations. An index fund is invested in the same securities as the index and so requires minimal management and should have minimal management fees or costs.

Mutual funds are created and managed by mutual fund companies or by brokerages or even banks. To trade shares of a mutual fund you must have an account with the company, brokerage, or bank. Mutual funds are a large component of individual retirement accounts and of defined contribution plans.

Mutual fund shares are valued at the close of trading each day and orders placed the next day are executed at that price until it closes. An exchange-traded fund (ETF) is a mutual fund that tracks an index or a commodity or a basket of assets, but is traded like stocks on a stock exchange. An ETF trades like a share of stock in that it is valued continuously throughout the day, and trades are executed at the market price.

The ways that capital can be bought and sold is limited only by the imagination. When corporations or governments need financing, they invent ways to entice investors and promise them a return. The last thirty years have seen an explosion in financial engineering, the innovation of new financial instruments through mathematical pricing models. This explosion has coincided with the ever-expanding powers of the computer, allowing professional investors to run the millions of calculations involved in sophisticated pricing models. The Internet also gives amateurs instantaneous access to information and accounts.

Much of the modern portfolio theory that spawned these innovations (i.e., the idea of using the predictability of returns to manage portfolios of investments) is based on an infinite time horizon, looking at performance over very long periods of time. This has been very valuable for institutional investors (e.g., pension funds, insurance companies, endowments, foundations, and trusts) as it gives them the chance to magnify returns over their infinite horizons.

For most individual investors, however, most portfolio theory may present too much risk or just be impractical. Individual investors don’t have an infinite time horizon, but rather a comparatively small amount of time to create wealth and to enjoy it. For individual investors, investing is a process of balancing the demands and desires of returns with the costs of risk, before time runs out.

Key Takeaways

- Bonds are:

• a way to raise capital through borrowing, used by corporations and governments;

• an investment for the bondholder that creates return through regular, fixed, or floating interest payments on the debt and the repayment of principal at maturity; and

• traded on bond exchanges through brokers. - Stocks are:

• a way to raise capital through selling ownership or equity;

• an investment for shareholders that creates return through the distribution of corporate profits as dividends or through gains (losses) in corporate value; and

• traded on stock exchanges through member brokers. - Commodities are:

• natural or cultivated resources;

• traded to hedge revenue or production needs or to speculate on resources’ prices; and

• traded on commodities exchanges through brokers. - Derivatives are instruments based on the future, and therefore uncertain, price of another security, such as a share of stock, a government bond, a currency, or a commodity.

- Mutual funds are portfolios of investments designed to achieve maximum diversification with minimal cost through economies of scale.

- An index fund is a mutual fund designed to replicate the performance of an asset class or selection of investments listed on an index.

- An exchange-traded fund is a mutual fund whose shares are traded on an exchange.

- Institutional and individual investors differ in the use of different investment instruments and in using them to create appropriate portfolios.

Exercises

- In your personal finance journal, record your experiences with investing. What investments have you made, and how much do you have invested? What stocks, bonds, funds, or other instruments described in this section do you have now (or have had in the past)? How were the decisions about your investments made, and who made them? If you have had no personal experience with investing, explain your reasons. What reasons might you have for investing (or not) in the future?

- Please review the article “Stock Exchanges Around the World” found on Investopedia’s website. Roughly how many stock exchanges exist in the world? Which geographic region has the greatest number of exchanges?

- Visit the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. What are some examples of commodities on the CME that theoretically could be part of your investment portfolio?

REFERENCES

Cooper, T. (2016). “Finance and Banking.” In K. Brown, M. Doucette, and J. Tulk, eds., Indigenous Business in Canada, pp.161–176. Sydney, NS: Cape Breton University Press.

Tulo Centre of Indigenous Economics. (2014). Building a Competitive First Nation Investment Climate. Retrieved from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/55565d7ae4b0447c46dd53e8/t/559c0405e4b0b280226825cc/1436288005495/tulotextbook.pdf.

12.2 INVESTMENT PLANNING

Learning Objectives

- Describe the advantages of the investment policy statement as a useful framework for investment planning.

- Identify the process of defining investor return objectives.

- Identify the process of defining investor risk tolerance.

- Identify investor constraints or restrictions on an investment strategy.

Allison has a few hours to kill while her flight home is delayed. She loves her job as an analyst for a management consulting firm, but the travel is getting old. As she gazes at the many investment magazines and paperbacks on display and the several screens all tuned to financial news networks and watches people hurriedly checking their stocks on their mobile phones, she begins to think about her own investments. She has been paying her bills, paying back student loans, and trying to save some money for a while. Her uncle just died and left her a bequest of $50,000. She is thinking of investing it since she is getting by on her salary and has no immediate plans for this windfall.

Allison is wondering how to get into some serious investing. There is no lack of information or advice about investing, but Allison isn’t sure how to get started.

Allison may not realize that there are as many different investment strategies as there are investors. The planning process is similar to planning a budget or savings plan. You determine where you are, where you want to be, and how to get there. One way to get started is to draw up an individual investment policy statement.

Investment policy statements are outlines of the investor’s goals and constraints, and they are popular with institutional investors such as pension plans, insurance companies, or non-profit endowments. Institutional investment decisions are typically made by professional managers operating on instructions from a higher authority, usually a board of directors or trustees. The directors or trustees may approve the investment policy statement and then leave the specific investment decisions up to the professional investment managers. The managers use the policy statement as their guide to the directors’ wishes and concerns.

This idea of a policy statement has been adapted for individual use, providing a helpful, structured framework for investment planning—and thinking. The advantages of drawing up an investment policy to use as a planning framework include the following:

- The process of creating the policy requires thinking through your goals and expectations and adjusting those to what is possible.

- The policy statement gives you an active role in your investment planning, even if the more specific details and implementation are left to a professional investment adviser.

- Your policy statement is portable, so even if you change advisers, your plan can go with you.

- Your policy statement is flexible; it can and should be updated at least once a year.

A policy statement is written in two parts. The first part lists your return objectives and risk preferences as an investor. The second part lists your constraints on investment. It is sometimes difficult to reconcile the two parts, so you may need to adjust your statement to improve your chances of achieving your return objectives within your risk preferences without violating your constraints.

Defining Return Objectives and Risk Tolerance

Defining return objectives is the process of quantifying the required annual return (e.g., 5 per cent, 10 per cent, etc.) necessary to meet your investment goals. If your investment goals are vague (e.g., to “increase wealth”), then any positive return will do. Usually, however, you have some specific goals—for example, to finance a child’s or grandchild’s education, to have a certain amount of wealth at retirement, to buy a sailboat on your fiftieth birthday, and so on.

Once you have defined goals, you must determine when they will happen and how much they will cost, or how much you will have to have invested to make your dreams come true. As explained in Chapter 4 “Evaluating Choices: Time, Risk, and Value,” the rate of return that your investments must achieve to reach your goals depends on how much you have to invest to start with, how long you have to invest it, and how much you need to fulfill your goals.

As in Allison’s case, your goals may not be so specific. Your thinking may be more along the lines of, “I want my money to grow and not lose value,” or, “I want the investment to provide a little extra spending money until my salary rises as my career advances.” In that case, your return objective can be calculated based on the role that these funds play in your life: safety net, emergency fund, extra spending money, or nest egg for the future.

However specific (or not) your goals may be, the quantified return objective defines the annual performance that you demand from your investments. Your portfolio can then be structured—you can choose your investments—such that it can be expected to provide that performance.

If your return objective is more than can be achieved given your investment and expected market conditions, then you know to scale down your goals, or perhaps find a different way to fund them. For example, if Allison wanted to stop working in ten years and start her own business, she probably would not be able to achieve this goal solely by investing her $50,000 inheritance, even in a bull (up) market earning higher rates of return.

As you saw in Chapter 10 “Personal Risk Management: Insurance” and Chapter 11 “Personal Risk Management: Retirement and Estate Planning,” in investing there is a direct relationship between risk and return, and risk is costly. The nature of these relationships has fascinated and frustrated investors since the origin of capital markets, and it remains a subject of investigation, exploration, and debate. To invest is to take risk. To invest is to separate yourself from your money through actual distance—you literally give it to someone else—or through time. There is always some risk that what you get back is worth less (or costs more) than what you invested (a loss), or is less than what you might have had if you had done something else with your money (opportunity cost). The more risk you are willing to take, the more potential return you can make, but the higher the risk, the more potential losses and opportunity costs you may incur.

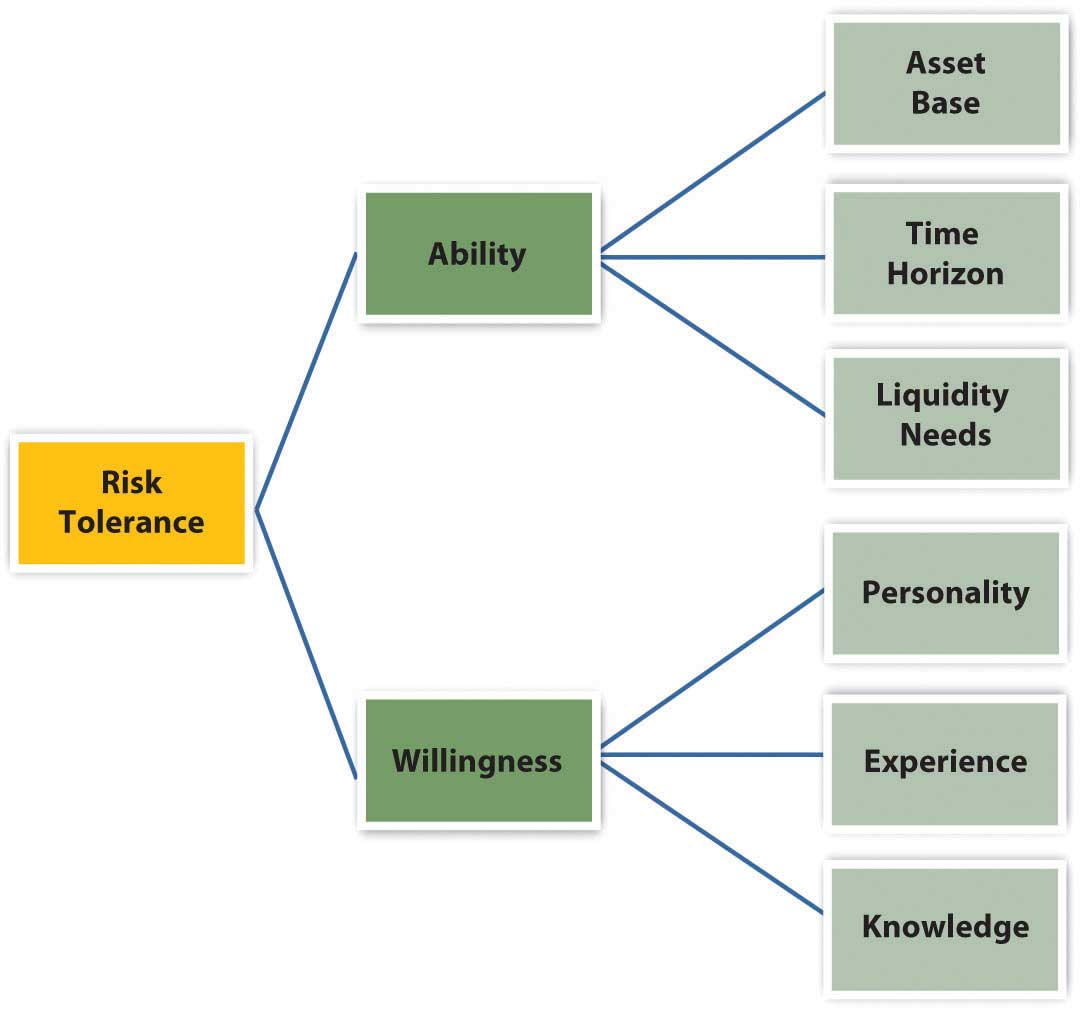

Individuals have different risk tolerances. Your risk tolerance is your ability and willingness to assume risk. Your ability to assume risk is based on your asset base, your time horizon, and your liquidity needs. In other words, your ability to take investment risks is limited by how much you have to invest, how long you have to invest it, and your need for your portfolio to provide cash—for use rather than reinvestment—in the meantime.

Your willingness to take risk is shaped by your “personality,” your experiences, and your knowledge and education. Attitudes are shaped by life experiences, and attitudes toward risk are no different. Chart 12.2.1 shows how your level of risk tolerance develops.

Chart 12.2.1 Risk Tolerance

Investment advisers may try to gauge your attitude toward risk by having you answer a series of questions on a formal questionnaire or by just talking with you about your investment approach. For example, an investor who says, “It’s more important to me to preserve what I have than to make big gains in the markets,” is relatively risk averse. The investor who says, “I just want to make a quick profit,” is probably more of a risk seeker.

Once you have determined your return objective and risk tolerance (i.e., what it will take to reach your goals and what you are willing and able to risk to get there) you may have to reconcile the two. You may find that your goals are not realistic unless you are willing to take on more risk. If you are unwilling or unable to take on more risk, you may have to scale down your goals.

Defining Constraints

Defining constraints is a process of recognizing any limitation that may impede or slow or divert progress toward your goals. The more you can anticipate and include constraints in your planning, the less likely they will throw you off course. Constraints include the following:

- Liquidity needs,

- Time available,

- Tax obligations,

- Legal requirements, and

- Unique circumstances.

Liquidity needs, or the need to use cash, can slow your progress from investing because you have to divert cash from your investment portfolio in order to spend it. In addition, you will have ongoing expenses from investing. For example, you will have to use some liquidity to cover your transaction costs such as brokerage fees and management fees. You may also wish to use your portfolio as a source of regular income or to finance asset purchases, such as the down payment on a home or a new car or new appliances.

While these may be happy transactions for you, for your portfolio they are negative events, because they take away value from your investment portfolio. Since your portfolio’s ability to earn returns is based on its value, whenever you take away from that value, you are reducing its ability to earn.

Time is another determinant of your portfolio’s earning power. The more time you have to let your investments earn, the more earnings you can amass. Or, the more time you have to reach your goals, the more slowly you can afford to get there, earning less return each year but taking less risk as you do. Your time horizon will depend on your age and life stage and on your goals and their specific liquidity needs.

Tax obligations are another constraint, because paying taxes takes value away from your investments. Investment value may be taxed in many ways (as income tax, capital gains tax, property tax, estate tax, or gift tax) depending on how it is invested, how its returns are earned, and how ownership is transferred if it is bought or sold.

Investors typically want to avoid, defer, or minimize paying taxes, and some investment strategies will do that better than others. In any case, your individual tax liabilities may become a constraint in determining how the portfolio earns to best avoid, defer, or minimize taxes.

Legalities also can be a constraint if the portfolio is not owned by you as an individual investor but by a personal trust or a family foundation. Trusts and foundations have legal constraints defined by their structure.

“Unique circumstances” refer to your individual preferences, beliefs, and values as an investor. For example, some investors believe in socially responsible investing (SRI), so they want their funds to be invested in companies that practise good corporate governance, responsible citizenship, fair trade practices, or environmental stewardship.

Some investors don’t want to finance companies that make objectionable products or by-products or have labour or trade practices reflecting objectionable political views. Divestment is the term for taking money out of investments. Grassroots political movements often include divestiture campaigns, such as student demands that their universities stop investing in companies that do business with nondemocratic or oppressive governments.

Socially responsible investment is the term for investments based on ideas about products or businesses that are desirable or objectionable. These qualities exist in the eye of the beholder, however, and vary among investors. Your beliefs and values are unique to you and to your circumstances in investing, and they may change over time. For more information on socially responsible investing in Canada, please go to the following websites:

- US SIF: The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment

- Rocky Mountain Humane Investing

- Responsible Investment Association (RIA)

- The Globe and Mail article “Confused by ethical investing? Here’s a primer“

Having mapped out your goals and determined the risks you are willing to take, and having recognized the limitations you must work with, you and/or your investment advisers can now choose the best investments. Different advisers may have different suggestions based on your investment policy statement. The process of choosing involves knowing what returns and risks investments have produced in the past, what returns and risks they are likely to have in the future, and how the returns and risks are related—or not—to each other.

Key Takeaways

- The investment policy statement provides a useful framework for investment planning because:

• the process of creating the policy requires thinking through goals and expectations and adjusting those to the possible;

• the statement gives the investor an active role in investment planning, even if the more specific details and implementation are left to a professional investment adviser;

• the statement is portable, so that even if you change advisers your plans can go with you; and

• the statement is flexible; it can and should be updated at least once per year. - Return objectives are defined by the investor’s goals, time horizon, and value of the asset base.

- Risk tolerance is defined by the investor’s ability and willingness to assume risk; comfort with risk-taking relates to personality, experience, and knowledge.

- Constraints or restrictions to an investment strategy are the investor’s

• liquidity needs,

• time horizon,

• tax circumstances and obligations,

• legal restrictions, and

• unique preferences or circumstances. - Socially responsible investment and divestment are unique preferences based on beliefs and values about desirable or objectionable industries, products, or companies.

- Your investment policy statement guides the selection of investments and development of your investment portfolio.

Exercises

- Brainstorm with classmates expressions relating to investing, such as, “you gotta pay to play”; “you gotta play to win”; “no pain, no gain”; “it takes money to make money,” and so on. What does each of these expressions really mean? How do they relate to the concepts of investment risk and return on investment? In what ways are risks and returns in a reciprocal relationship?

- Draft an individual investment policy statement as a guide to your future investment planning. What will be the advantages of having an investment policy statement? In your personal finance journal, record your general return objectives and specific goals at this time. What is a return objective?

- What is your level of risk tolerance? How would you rate your risk tolerance on a five-point scale (with one indicating “most risk averse”)? In your personal finance journal, record how your asset base, time horizon, and liquidity needs define your ability to undertake investment risk. Then describe the personality characteristics, past experiences, and knowledge base that you feel help shape your degree of willingness to undertake risk. Now check your beliefs by using Sun Life Financial’s investment risk profiler on the webpage Calculate your risk profile. How do the results compare with your estimate? What conclusions do you draw from this test? What percentage of your investments do you now think you could put into stocks? What factor could you change that might enable you to tolerate more risk?

- In your personal finance journal, record the constraints you face when it comes to reaching your investment goals. With what types of constraints must you reconcile with your investment planning? The more you need to use your money to live and the less time you have to achieve your goals, the greater the constraints in your investment planning. Revise your statement of goals and return objectives as needed to ensure it is realistic in light of your constraints.

- In collaboration with classmates, conduct an online investigation into socially responsible investing. Review the websites noted in the section above on socially responsible investment. On the basis of your investigation, outline and discuss the different forms and purposes of SRI. Which form and purpose appeal most to you and why? What investments might you make, and what investments might you specifically avoid, to express your beliefs and values? Do you think investment planning could ever have a role in bringing about social change?

12.3 MEASURING RETURN AND RISK

Learning Objectives

- Characterize the relationship between risk and return.

- Describe the differences between actual and expected returns.

- Explain how actual and expected returns are calculated.

- Define investment risk and explain how it is measured.

- Define the different kinds of investment risk.

You want to choose investments that will combine to achieve the return objectives and level of risk that’s right for you, but how do you know what the right combination will be? You can’t predict the future, but you can make an educated guess based on an investment’s past history. To do this, you need to know how to read or use the information available. Perhaps the most critical information to have about an investment is its potential return and susceptibility to types of risk.

Return

Returns are always calculated as annual rates of return, or the percentage of return created for each unit (dollar) of original value. If an investment earns 5 per cent, for example, that means that for every $100 invested, you would earn $5 per year (because $5 = 5% of $100).

Returns are created in two ways: the investment creates income or the investment gains (or loses) value. To calculate the annual rate of return for an investment, you need to know the income created, the gain (loss) in value, and the original value at the beginning of the year. The percentage return can be calculated as in Table 12.3.1.

|

Note that if the ending value is greater than the original value, then ending value − (minus) original value > 0 (is greater than zero), and you have a gain that adds to your return. If the ending value is less, then ending value − (minus) original value < 0 (is less than zero), and you have a loss that detracts from your return. If there is no gain or loss, if ending value − (minus) original value = 0 (is the same), then your return is simply the income that the investment created.

For example, if you buy a share of stock for $100, and it pays no dividend, and a year later the market price is $105, then your return = [0 + (105 − 100)] / 100 = 5 / 100 = 5%. If the same stock paid a dividend of $2, then your return = [2 + (105 − 100)] / 100 = 7 / 100 = 7%.

If the information you have shows more than one year’s results, you can calculate the annual return using what you learned in Chapter 4 “Evaluating Choices: Time, Risk, and Value” about the relationships of time and value. For example, if an investment was worth $10,000 five years ago and is worth $14,026 today, then $10,000 × (1 + r)5 = $14,026. Solving for r, the annual rate of return, you get 7 per cent. So, other factors being equal, the $10,000 investment must have earned at a rate of 7 per cent per year to be worth $14,026 five years later.

While information about current and past returns is useful, investment professionals are more concerned with the expected return for the investment—that is, how much it may be expected to earn in the future. Estimating the expected return is complicated because many factors (e.g., current economic conditions, industry conditions, and market conditions) may affect that estimate.

For investments with a long history, a strong indicator of future performance may be past performance. Economic cycles fluctuate, and industry and firm conditions vary, but over the long run, an investment that has survived has weathered all those storms. So, you could look at the average of the returns for each year. There are several ways to do the math, but if you look at the average return for different investments of the same asset class or type (e.g., stocks of large companies) you could compare what they have returned, on average, over time.

If the time period you are looking at is long enough, you can reasonably assume that an investment’s average return over time is the return you can expect in the next year. For example, if a company’s stock has returned, on average, 9 per cent per year over the last twenty years, then if next year is an average year, that investment should return 9 per cent again. Over the eighteen-year span from 1990 to 2008, for example, the average return for the S&P 500 was 9.16 per cent. Unless you have some reason to believe that next year will not be an average year, the average return can be your expected return. The longer the time period you consider, the less volatility there will be in the returns, and the more accurate your prediction of expected returns will be.

Returns are the value created by an investment, through either income or gains. Returns are also your compensation for investing, for taking on some or all of the risk of the investment, whether it is a corporation, government, parcel of real estate, or work of art. Even if there is no risk, you must be paid for the use of liquidity that you give up to the investment (by investing).

Returns are the benefits from investing, but they must be larger than its costs. There are at least two costs to investing: the opportunity cost of giving up cash and giving up all your other uses of that cash until you get it back in the future, and the cost of the risk you take—the risk that you won’t get it all back.

Risk

Investment risk is the idea that an investment will not perform as expected, that its actual return will deviate from the expected return. Risk is measured by the amount of volatility—that is, the difference between actual returns and average (expected) returns. This difference is referred to as the standard deviation. Returns with a large standard deviation (showing the greatest variance from the average) have higher volatility and are the riskier investments.

An investment may do better or worse than its average. Standard deviation can therefore be used to define the expected range of investment returns. For the S&P 500, for example, the standard deviation from 1990 to 2008 was 19.54 per cent. So, in any given year, the S&P 500 is expected to return 9.16 per cent, but its return could be as high as 67.78 per cent or as low as −49.46 per cent, based on its performance during that specific period.

What risks are there? What would cause an investment to unexpectedly over or underperform? Starting from the top (the big picture) and working down, there are

- economic risks,

- industry risks,

- company risks,

- asset class risks, and

- market risks.

Economic risks are risks that something will upset the economy as a whole. The economic cycle may swing from expansion to recession, for example; inflation or deflation may increase, unemployment may increase, or interest rates may fluctuate. These macroeconomic factors affect everyone doing business in the economy. Most businesses are cyclical, growing when the economy grows and contracting when the economy contracts.

Consumers tend to spend more disposable income when they are more confident about economic growth and the stability of their jobs and incomes. They also tend to be more willing and able to finance purchases with debt or with credit, expanding their ability to purchase durable goods. So, demand for most goods and services increases as an economy expands, and businesses expand too. An exception is businesses that are countercyclical. Their growth accelerates when the economy is in a downturn and slows when the economy expands. For example, low-priced fast food chains typically have increased sales in an economic downturn because people substitute fast food for more expensive restaurant meals as they worry more about losing their jobs and incomes.

Industry risks usually involve economic factors that affect an entire industry or developments in technology that affect an industry’s markets. An example is the effect of a sudden increase in the price of oil (a macroeconomic event) on the airline industry. Every airline is affected by such an event, as an increase in the price of airplane fuel increases airline costs and reduces profits. An industry such as real estate is vulnerable to changes in interest rates. A rise in interest rates, for example, makes it harder for people to borrow money to finance purchases, which depresses the value of real estate.

Company risk refers to the characteristics of specific businesses or firms that affect their performance, making them more or less vulnerable to economic and industry risks. These characteristics include how much debt financing the company uses, how well it creates economies of scale, how efficient its inventory management is, how flexible its labour relationships are, and so on.

The asset class that an investment belongs to can also bear on its performance and risk. Investments (assets) are categorized in terms of the markets they trade in. Broadly defined, asset classes include:

- corporate stock or equities (shares in public corporations, either domestic or foreign);

- bonds or the public debts of corporations or governments;

- commodities or resources (e.g., oil, coffee, or gold);

- derivatives or contracts based on the performance of other underlying assets;

- real estate (both residential and commercial); and

- fine art and collectibles (e.g., stamps, coins, baseball cards, or vintage cars).

Within those broad categories, there are finer distinctions. For example, corporate stock is classified as large cap, mid cap, or small cap, depending on the size of the corporation as measured by its market capitalization (the aggregate value of its stock). Bonds are distinguished as corporate or government and as short-, intermediate-, or long-term, depending on the maturity date.

Risks can affect entire asset classes. Changes in the inflation rate can make corporate bonds more or less valuable, for example, or more or less able to create valuable returns. In addition, changes in a market can affect an investment’s value. When the stock market fell unexpectedly and significantly, as it did in 1929, 1987, and 2008, all stocks were affected, regardless of relative exposure to other kinds of risk. After such an event, the market is usually less efficient or less liquid—that is, there is less trading and less efficient pricing of assets (stocks) because there is less information flowing between buyers and sellers. The loss in market efficiency further affects the value of assets traded.

As you can see, the link between risk and return is reciprocal. The question for investors and their advisers is: How can you get higher returns with less risk?

Key Takeaways

- There is a direct relationship between risk and return because investors will demand more compensation for sharing more investment risk.

- Actual return includes any gain or loss of asset value plus any income produced by the asset during a period.

- Actual return can be calculated using the beginning and ending asset values for the period and any investment income earned during the period.

- Expected return is the average return the asset has generated based on historical data of actual returns.

- Investment risk is the possibility that an investment’s actual return will not be its expected return.

- The standard deviation is a statistical measure used to calculate how often and how far the average actual return differs from the expected return.

- Investment risk is exposure to:

• economic risk,

• industry risk,

• company- or firm-specific risk,

• asset class risk, or

• market risk.

Exercises

- Selecting a security to invest in, such as a stock or fund, requires analyzing its returns. You can view the annual returns as well as average returns over a five-, ten-, fifteen-, or twenty-year period. Charts of returns can show the amount of volatility in the short term and over the longer term. What do you need to know to calculate the annual rate of return for an investment?

- The standard deviation on the rate of return on an investment is a measure of its volatility or risk. What would a standard deviation of zero mean? What would a standard deviation of 10 per cent mean?

- What kinds of risk are included in investment risk? Go online to survey current or recent financial news. Find and present a specific example of the impact of each type of investment risk. In each case, how did the type of risk affect investment performance?

12.4 DIVERSIFICATION: RETURN WITH LESS RISK

Learning Objectives

- Explain the use of diversification in a portfolio strategy.

- List the steps in creating a portfolio strategy, explaining the importance of each step.

- Compare and contrast active and passive portfolio strategies.

Every investor wants to maximize return, the earnings or gains from giving up surplus cash. And every investor wants to minimize risk, because it is costly. To invest is to assume risk, and you assume risk expecting to be compensated through return. The more risk assumed, the more the promised return. So, to increase return you must increase risk, and to lessen risk, you must expect less return. But another way to lessen risk is to diversify: to spread out your investments among a number of different asset classes. Investing in different asset classes reduces your exposure to economic, asset class, and market risks.

Concentrating investment concentrates risk. Diversifying investments spreads risk by having more than one kind of investment and thus more than one kind of risk. To truly diversify, you need to invest in assets that are not vulnerable to one or more kinds of risk. For example, you may want to diversify:

- between cyclical and countercyclical investments, reducing economic risk;

- among different sectors of the economy, reducing industry risks;

- among different kinds of investments, reducing asset class risk; and

- among different kinds of firms, reducing company risks.

To diversify well, you have to look at your collection of investments as a whole—that is, as a portfolio rather than as a gathering of separate investments. If you choose the investments well, if they are truly different from each other, the whole can actually be more valuable than the sum of its parts.

Steps to Diversification

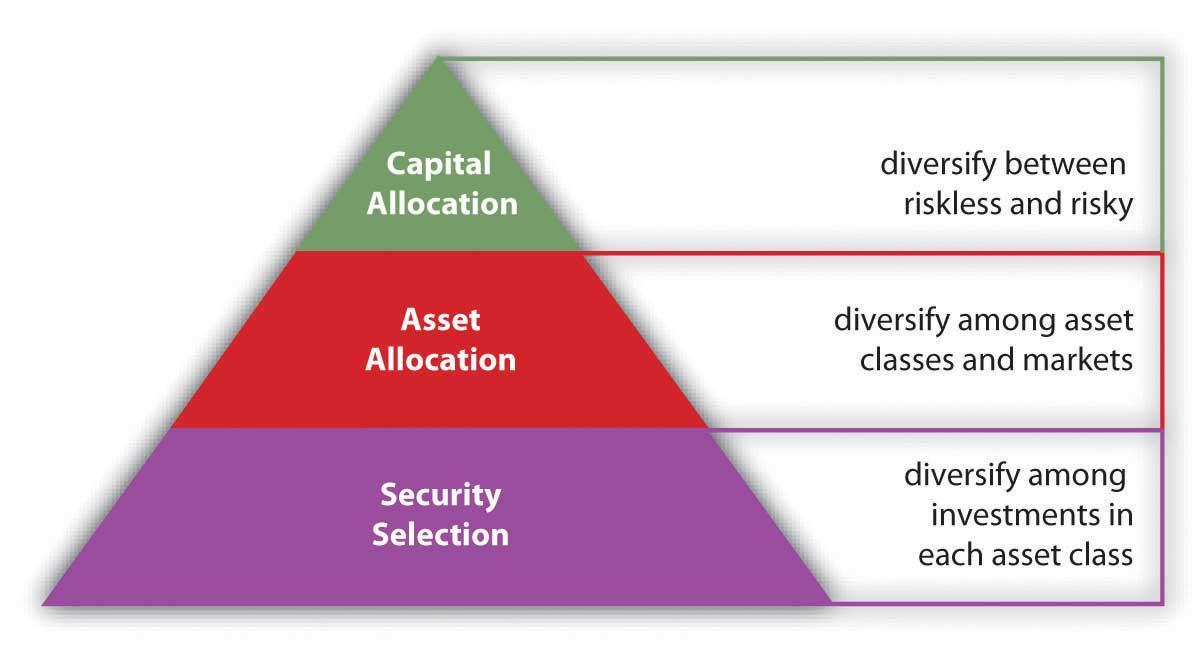

In traditional portfolio theory, there are three levels or steps to diversifying: capital allocation, asset allocation, and security selection.

Capital allocation is diversifying your capital between risky and riskless investments. A “riskless” asset is a short-term (less than ninety-day) government treasury bill. Because it has such a short time to maturity, it won’t be much affected by interest rate changes, and it is probably impossible for the Canadian government to become insolvent—go bankrupt—and have to default on its debt within such a short time.

The capital allocation decision is the first diversification decision. It determines the portfolio’s overall exposure to risk, or the proportion of the portfolio that is invested in risky assets. That, in turn, will determine the portfolio’s level of return.

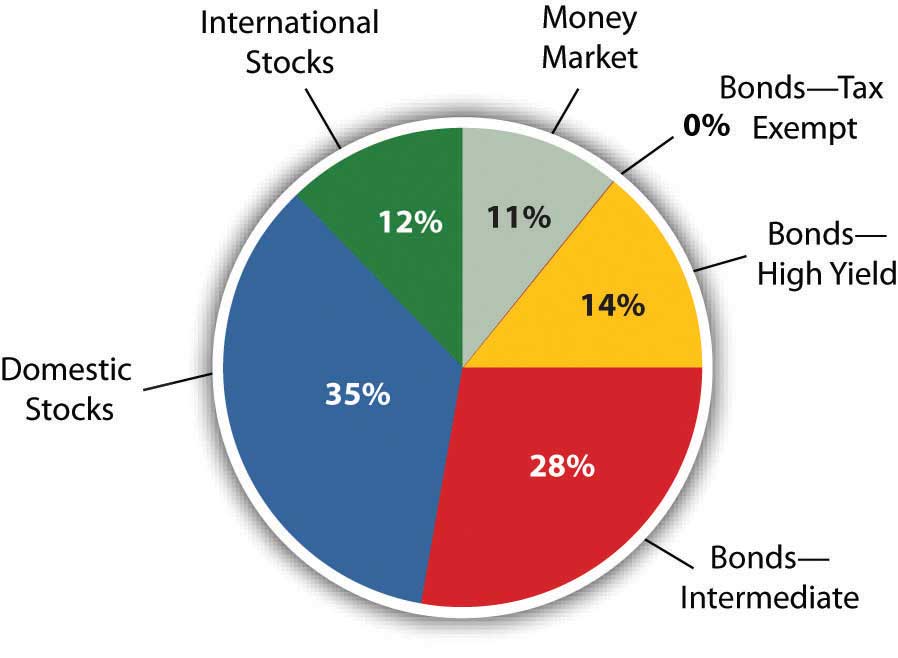

The second diversification decision is asset allocation: deciding which asset classes, and therefore which risks and which markets, to invest in. Asset allocations are specified in terms of the percentage of the portfolio’s total value that will be invested in each asset class. To maintain the desired allocation, the percentages are adjusted periodically as asset values change. Chart 12.4.1 shows an asset allocation for an investor’s portfolio.

Chart 12.4.1 Proposed Asset Allocation

Asset allocation is based on the expected returns and relative risk of each asset class and how it will contribute to the return and risk of the portfolio as a whole. If the asset classes you choose are truly diverse, then the portfolio’s risk can be lower than the sum of the assets’ risks.

One example of an asset allocation strategy is life cycle investing—changing your asset allocation as you age. When you retire, for example, and forgo income from working, you become dependent on income from your investments. As you approach retirement age, therefore, you typically shift your asset allocation to less risky asset classes to protect the value of your investments.

Security selection is the third step in diversification: choosing individual investments within each asset class. Here is the chance to achieve industry or sector and company diversification. For example, if you decided to include corporate stock in your portfolio (asset allocation), you decide which corporation’s stock to invest in. Choosing corporations in different industries, or companies of different sizes or ages, will diversify your stock holdings. You will have less risk than if you invested in just one corporation’s stock. Diversification is not defined by the number of investments but by their different characteristics and performance.

Investment Strategies

Capital allocation decides the amount of overall risk in the portfolio; asset allocation tries to maximize the return you can get for that amount of risk. Security selection further diversifies within each asset class. Chart 12.4.2 demonstrates the three levels of diversification.

Chart 12.4.2 Levels of Diversification

Just as life cycle investing is a strategy for asset allocation, investing in index funds is a strategy for security selection. Indexes are a way of measuring the performance of an entire asset class by measuring returns for a portfolio containing all the investments in that asset class. Essentially, the index becomes a benchmark for the asset class, a standard against which any specific investment in that asset class can be measured. An index fund is an investment that holds the same securities as the index, so it provides a way for you to invest in an entire asset class without having to select particular securities.

There are indexes and index funds for most asset classes. By investing in an index, you are achieving the most diversification possible for that asset class without having to make individual investments—that is, without having to make any security selection decisions. This strategy of bypassing the security selection decision is called passive management. It also has the advantage of saving transaction costs (broker’s fees) because you can invest in the entire index through only one transaction rather than the many transactions that picking investments would require.

In contrast, making security selection decisions to maximize returns and minimize risks is called active management. Investors who favour active management feel that the advantages of picking specific investments, after careful research and analysis, are worth the added transaction costs. Actively managed portfolios may achieve diversification based on the quality, rather than the quantity, of securities selected.

Also, asset allocation can be actively managed through the strategy of market timing—shifting the asset allocation in anticipation of economic shifts or market volatility. For example, if you forecast a period of higher inflation, you would reduce allocation in fixed-rate bonds or debt instruments, because inflation erodes the value of the fixed repayments. Until the inflation passes, you would shift your allocation so that more of your portfolio is in stocks, say, and less in bonds.

It is rare, however, for active investors or investment managers to achieve superior results over time. More commonly, an investment manager is unable to achieve consistently better returns within an asset class than the returns of the passively managed index (Malkiel, 2007).

Key Takeaways

- Diversification can decrease portfolio risk by allowing you to choose investments with different risk characteristics and exposures.

- A portfolio strategy involves:

• capital allocation decisions,

• asset allocation decisions, and

• security selection decisions. - Active management is a portfolio strategy including security selection decisions and market timing.

- Passive management is a portfolio strategy omitting security selection decisions and relying on index funds to represent asset classes, while maintaining a long-term asset allocation.

Exercises

- What is the meaning of the following expressions: “Don’t count your chickens before they hatch,” and “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket”? How do they relate to the challenge of reducing exposure to investment risks and building a high-performance investment portfolio?

- Do you favour an active or a passive investment management strategy? Why? Identify all the pros and cons of these investment strategies and debate them with classmates. What factors favour an active approach? What factors favour a passive approach? Which strategy might prove more beneficial for first-time investors?

REFERENCES

Malkiel, B. G. (2007). A Random Walk Down Wall Street, 10th ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.