Chapter 14: Providing Good Nutrition

Read Time: 55 Mins

Growth and Development During the First Year

Using Growth Charts to Track Developmental Milestones

Maturation of the Gastrointestinal Track

Breastfeeding

Maturation of the Renal System

Formula Feeding

When to Feed

Introducing Solid Foods

Transition Process to Family Meals

Learning to Self-Feed

Supporting Infant Nutrition

Self-Feeding

Feeding Challenges in the Toddler Years

Feeding Challenges in the Preschool Years

Typical Picky Eating Behaviours

Trying New Foods

School Meals

Meals and Snacks in School-Aged Care Programs

Feeding Children with Disabilities

References

Chapter 14 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the changes in nutritional needs as children mature (get older).

- Advocate for the support of breastfeeding mothers.

- Relate bottle-feeding practices.

- Discuss the transition to solid foods and self-feeding.

- Summarize feeding challenges for toddlers.

- Explain effective ways to respond to picky eating.

- Outline the importance of inclusive nutrition policies and practices.

- Identify how to support children with unique nutritional and feeding needs.

Introduction

To provide all children with the appropriate nutrition, it is important to understand how nutritional needs and feeding practices change as children mature. Children with special needs may have different nutritional and feeding needs. Working with families and medical providers, programs can ensure that they meet each and every child’s needs. Early care and education programs can also support and empower families to provide the best nutrition to their children.

The first two to five years of a child’s life are a huge window of opportunity for setting up a healthy life. Choices parents are making during this time not only allow the child to grow to their full potential, but set up the metabolism, educate the immune system, determine taste preferences, and develop the child’s eating pattern. These choices will make it easier or more difficult for the child to live a healthy life later on.

Growth and Development During the First Year [1]

Generations in the past were much more relaxed about it. You brought your baby home and fed the baby with the recommended amount of baby formula. During the 1950s, 60s and 70s it was thought that formula was better and more convenient than breast milk. Few women nursed their babies. Next, parents started feeding food from baby jars and transitioned the baby to the food the family ate. If the baby grew well and was kind of chubby, you were doing a good job as a parent. Once the child ate at the table, the child needed to eat what was served and clear the plate.

Today, things seem much more complicated. Scientifically, we know much more about the factors that allow newborns to grow to their full potential metabolically. We have started to understand the amazing ways nature reacts to environmental stimulants by developing metabolism, immune system, and eating habits that are adjusted to the environment the infant is living in. We also have learned that nature is misinterpreting the modern Western living stimulants. From a scientific standpoint, things have become more complicated and new parents tend to feel this pressure.

Using Growth Charts to Track Developmental Milestones [2]

From birth to 24 months the health care provider will use growth charts to track the weight, length, weight-for-length and head circumference development. Those infant growth charts are based on growth data from thousands of breastfed infants and are separated into male and female charts.

Once the child reaches age two a second growth chart is used to track growth development until age 19. The second set of growth charts, one for males and one for females tracks weight, height and BMI for age. A weight for stature chart is also used.

Newborns come in all sizes. A term infant is born between 37 and 42 weeks. Medically we distinguish between early term (37 to 38 weeks), full term (39 to 40 weeks) and late term (41 to 42 weeks). You can imagine that depending on when infants are born they can range in size quite a bit.

In addition, genetic factors and the weight status of the mother determine the size of a newborn as well. Newborn boys are usually heavier than newborn girls, first babies tend to be smaller than their siblings, and large parents have generally larger newborns than smaller parents.

It is not surprising that birth weight can vary. The average newborn is 7.5 pounds but a normal birthweight can range from 5.5 to 10 pounds.

Growth Charts for Canada

Once the infants are born they shift from hemotropic nutrition (exchange of nutrients between the maternal and fetal blood circulations) to oral nutrition. During the first four to six months of life, infants are fed solely breastmilk or formula. The question is, given the range of newborn size, how much milk should an infant have each day? Shouldn’t a larger infant need more milk than a smaller infant?

It becomes even more complicated when the mother nurses her infant. When a mother nurses the baby latches onto the nipple and the baby drinks breast milk until it is full. This makes it difficult to track how much milk the baby drank. How do we know that the mother produces sufficient amounts of milk? Can an infant be overfed? With breastmilk? Formula? Some mothers may rely on crying to act as a hunger cue, but there may be other culprits such as a wet diaper, gas, or an ear infection.

Since determining the amount of milk needed to enable optimal growth is too complicated, determining the adequacy of nutrition is done a different way: Tracking the growth of the infant.

The Canadian Paediatric Society recommends six visits to the doctors during the first year. During those visits, the pediatrician checks the infant’s health and whether or not the infant is meeting developmental milestones. The nurse will also measure the weight, length, and head circumference of the infant and track those numbers on a growth chart. A typical schedule would be 3-5 days old, 1 month old, 2 months, 4 months, 6 months, 9 months and then 1 year[3].

If an infant starts going off track—this is usually first seen in the weight development followed later by the length development—the pediatrician needs to investigate. Reasons could be an underlying health condition, insufficient breast milk, late introduction of solids, or generally inadequate nutrition. Growth charts can help identify these problems early.

At birth, infants are charted on a growth chart and are placed into one of three categories based on their weight: small-for-gestational-age (SGA), large-for-gestational-age (LGA), or appropriate-for-gestational-age (AGA). SGA infants have a birth weight below the 10th percentile, while LGA infants have a birth weight above the 90th percentile. SGA and LGA newborns will usually grow into their genetically determined percentile during the first month.

Adjusted Gestational Age:

Premature infants cannot just be plotted by their postnatal, chronological age. Age calculation needs to be adjusted by gestation. Subtract the infant’s gestational age at birth in weeks from 40 weeks (term infant). Subtract that number from the infant’s current age. An infant born at 30 weeks would have an adjustment of 10 weeks (40 – 30). At the 4-month (16-week) checkup, the measurements would be plotted against an age of 6 weeks (16 – 10).

Right after birth, a newborn will lose about 10% of their body weight. This weight loss is physiological and mostly water, specifically extracellular water. If newborns lose more than 10% of their body weight or do not gain the weight back by the 2-week mark, it is called failure to thrive and will require tests.

Failure to thrive is generally described as inadequate physical growth diagnosed by observation of growth over time using standard growth charts. There is no absolute definition, nor is there a standardized tool to diagnose it. It may be organic (caused by a disease or disorder) or inorganic (not caused by an identifiable disease or disorder). Growth chart percentile jumps of 2 or more often indicate an issue.

Interventions often focus on increasing calories and proteins by supplementing breastmilk or using a more concentrated formula. As the infant begins to eat solid foods, the caregiver should opt for nutrient-dense and fortified foods. It is also important to consider other risk factors for inorganic failure to thrive such as poverty, poor feeding practices, and excessive fussiness. It may be more difficult for caregivers to correct failure to thrive if these factors persist.

After birth, extra-uterine growth sets in at an incredible growth rate which is why infants require more calories per pound than any other age group. In general, infants should double their birth weight by 4-6 months and triple it by 12 months. Their length should double by 12 months. The growth velocity will sharply decrease throughout the first two years and their growth velocity will slow (see graph above.)

After about one year, the fast growth will end, and toddlers will start growing in spurts. Interestingly, those growth spurts are influenced by the seasons. Children grow more in the spring and early summer. This is often surprising to their parents since the child will not eat as much. Children are generally able to regulate their nutrient intake well if offered healthy food and left to decide how much they will eat. For the parents, this can cause anxiety since some children will go from eating next to nothing for days to eating ferociously everything in sight.

After birth, the body composition changes as well. Body water declines steeply from 70 – 83 % to 55 – 60% at 6 months. At the same time body fat increases reaching a peak around 6 months. Once the baby starts moving around, the chubby baby starts to slowly become slimmer and lean body mass increases.

We can easily see those rapid growth changes during the first year, but organ systems are going through rapid development as well.

Maturation of the Gastrointestinal Track [4]

When we think about the function of the gastrointestinal system, anatomy, digestive fluids, and enzymes come to mind. For optimal function, several other components need to be considered too: GI motility, barrier function, and gut microbiome. Development of is necessary fo the transition to solid food at 4-6 months.

Anatomical development: The anatomical differentiation of the fetal gut is usually completed within 20 weeks of gestation. This means that the major components—mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, rectum, and anus—are in place as well as the layers and functional cells of the long gastrointestinal passage. During the last trimester, the increase in the intestinal length and expansion of the surface area including villi and microvilli development takes place.

GI Motility: The gastrointestinal passage is not a shaped, inanimate hose food is slipping through. Instead, the compartments of the GI tract actively move the food (later called chyme in the stomach or bolus after leaving the stomach) forward from compartment to compartment. Within each compartment, the bolus is thoroughly mixed. This active transporting and mixing is called GI motility.

GI motility includes the wavelike muscle contractions that move the food or intestine content through the esophagus and intestines forward, strong contractions of the stomach mix the chyme, and segmentation— moving the small intestine content back and forth. In addition, paced stomach emptying ensures that not too many nutrients reach the small intestine at once. As you can imagine, the coordination of these muscle contractions is complicated.

Peristalsis, the forward movement, is functional at 29 – 30 weeks of gestation. This means the mechanism is ready at birth of a full term infant, but many premature infants (born before week 30) need to be fed parenterally because their GI tract is not functional yet. Coordinated sucking and swallowing develops between week 32 to 34. Term babies have a strong suck-and-swallow reflex and are ready to go. In fact, once sucking and swallowing is matured enough during pregnancy the fetus swallows about 450 ml of amniotic fluid per day.

Other parts of the GI motility do not fully develop until birth, and some infants are still developing good coordination of GI motility after they are born. It is thought that this is the reason for the feared colic in young infants.

Digestion: While the ability to produce digestive juices is developed in the third trimester—lactase activity, for example, is detectable at 34 weeks gestation—enzyme activity is low at birth. Lactase activity at week 34 is only at 30% of the level at birth. All other important enzymes to digest milk are very limited right at birth. This includes limited pancreatic lipase and bile acids for lipid digestion, and limited lactase and amylase for carbohydrate digestion.

The first feeding after birth triggers a digestive growth spurt in the first 24 hours of birth. This is the reason why the small amount of breast milk the mother produces at this point is sufficient.

Barrier Function: At birth, the small intestine is leaky. This allows larger immunoglobulins from the breast milk to pass through between the enterocytes into the blood stream. During the first days of life, gut closure—the rapid reduction of epithelial permeability—takes place.

This is only part of the barrier function of the gut. In addition to having a leak-proof gut epithelium, the exposure to environmental bacteria stimulates the development of the gut microbiome, which in turn, stimulates the immune system. Together gut microbiome, gut epithelium, and immune system in the gut form a barrier against pathogens during the first months of life (more details in chapter 15 The Road to a Healthy Gut Microbiome).

Gut Microbiome: The GI tract of the fetus is almost sterile. When the fetus passes through the birth canal the maternal vaginal microbiome is transferred to the newborn. Together, with environmental bacteria and skin bacteria from people holding and handling the newborn, commensal bacteria start to cultivate on all body surfaces including the GI tract. The further progression of the microbiome cultivation is determined by the type of milk fed.

While I listed those GI functions individually keep in mind that normal gastrointestinal function relies on integrated maturation of absorptive, secretory, and motor functions. Delays in any of those developments will result in disturbed gastrointestinal function. This can manifest in vomiting, abdominal distention, colic, and constipation.

Feeding Infants

As stated earlier, requirements for macronutrients and micronutrients on a per-kilogram basis are higher during infancy than at any other stage in the human life cycle. See the average calorie needs for infants in Table 14.1. An infant’s resting metabolic rate is two times that of an adult. These needs are affected by the rapid cell division that occurs during growth, which requires energy and protein, along with the nutrients that are involved in DNA synthesis.[5]

Table 14.1 – Average Calorie Needs for Infants[6]

| Sex/Age | Calories |

| Boys (0-6 months) | 472-645 calories |

| Girls (0-6 months) | 438-593 calories |

| Boys (6-12 months) | 645-844 calories |

| Girls (6-12 months) | 593-768 calories |

| Boys (1-2 years) | 844-1,050 calories |

| Girls (1-2 years) | 768-997 calories |

During this period, children are entirely dependent on their parents and other caregivers to meet these needs. For almost all infants six months or younger, breast milk is the best source to fulfill nutritional requirements. An infant may require feedings eight to twelve times a day or more in the beginning. After six months, infants can gradually begin to consume solid foods to help meet nutrient needs.

How often an infant wants to eat will also change over time due to growth spurts, which typically occur at about two weeks and six weeks of age, and again at about three months and six months of age.[7]

Breastfeeding

The dietary recommendations for infants are based on the nutritional content of human breast milk. Carbohydrates make up about 45 to 65 percent of the caloric content in breast milk. Protein makes up about 5 to 20 percent of the caloric content of breast milk. About 30 to 40 percent of the caloric content in breast milk is made up of fat. A diet high in unsaturated fat is necessary to encourage the development of neural pathways in the brain and other parts of the body.

Almost all of the nutrients that infants require can be met if they consume an adequate amount of breast milk. There are a few exceptions, though. Human milk is low in vitamin D, which is needed for calcium absorption and building bone, among other things. Breast milk is also low in vitamin K, which is required for blood clotting, and deficits could lead to bleeding or hemorrhagic disease. Infants are born with limited vitamin K, so supplementation may be needed initially and some states require a vitamin K injection after birth. Also, breast milk is not high in iron, but the iron in breast milk is well absorbed by infants. After four to six months, however, an infant needs an additional source of iron other than breast milk. Therefore, breastfed children often need to take a vitamin D supplement in the form of drops.[8]

Supporting Breastfeeding in Early Care and Education

Early care and education programs play an important role in supporting breastfeeding All staff members—despite their comfort or experience with breastfeeding—play an important role in breastfeeding promotion. They have an opportunity to share the facts about breastfeeding with families, and to help them decide what’s best for them and their babies.[9]

You can support breastfeeding mothers when you:

· Talk about why breastfeeding is so good for their infant.

· Tell them you want to care for breastfed infants and support breastfeeding mothers.

· Share other places in the community they can go to for help with breastfeeding.

· Share and discuss resources about breastfeeding.

· Try to time feedings to the mother’s schedule (being sure to respond to the infant’s needs and cues).

· Offer a place to nurse that is comfortable, quiet, and private.

· Communicate about their infant’s day. [11]

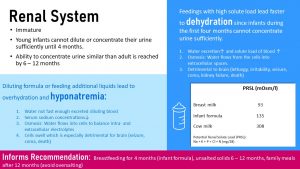

Maturation of the Renal System – [14]

At birth, the renal system of the newborn is still immature and needs to undergo maturation. The main problem is that the newborn infant cannot concentrate or dilute urine. The maximal urinary concentration in the neonatal period is less than 700 mOsm/kg, but reaches adult values of 1200 mOsm/kg by 6 to 12 months of life.

This means that the newborn needs to be fed a solution that has the right amount of electrolytes and a moderate amount of protein. Only breastmilk and formula fit the bill. An indicator of how much solutes a food produces during metabolism is the potential renal solute load or PRSL for short. The PRSL is calculated from the sodium, potassium, phosphorus, chloride, and nitrogen content of the milk. Breastmilk has a very low PRSL of 93 mOsm/l, formula is a little higher but still within the capability of newborn kidneys (135 mOsm/l). Feeding undiluted cow milk to a newborn would be detrimental with a PRSL of 308 mOsm/l.

After birth, the kidneys keep developing continuously and the ability to concentrate urine like an adult is reached by the age of 6 – 12 months. This maturation process informs dietary recommendations.

During the first four months, the infant should only be fed breastmilk or formula. Even water, diluted juice, or tea is not advised. After four months, the kidney function has progressed enough that solids can be slowly introduced. At this point, some water on a hot day is fine as well.

Until the end of the first year, solid food should not be salted to keep the amount of sodium needed for excretion in the urine low. After the first year, the child can participate in normal family meals, but parents should take care not to offer overly salty or processed foods.

Dehydration and Hyponatremia

What exactly would happen if parents decide to feed, on one hand, cows milk or concentrated formula, or on the other hand additional water or diluted formula? Keep in mind that this is not hypothetical. Parents might use more powder because they feel that their infant is not growing fast enough or dilute formula because money is running out at the end of the month and they cannot afford more formula.

Dehydration: If the infant is fed concentrated formula, cow’s milk, or cereal is added to the bottle—usually to help the infant sleep through the night—high amounts of sodium, potassium, phosphorus, chloride, and nitrogen circulate the bloodstream.

While glucose and triglycerides are completely metabolized to O2 and CO2, protein produces nitrogen that needs to be excreted. If an infant is fed high amounts of protein, the surplus is used for energy purposes. In the process, amino acids are deaminated and the carbon skeleton enters the energy metabolism. The nitrogen is incorporated into urea. The electrolytes and the excessive urea need to be excreted.

Since the kidneys are not able to concentrate the urine, large amounts of water need to be excreted along with the excessive amounts of solutes. This leads to dehydration even if the infant receives predominantly liquid foods. The water intake is lower than the large amounts of urine excreted.

As the dehydration progresses, the solute load of the blood increases as blood plasma declines. Osmosis, causes the water to shift from cells into the blood circulation. Cells shrink and that impacts the brain.

Initially, the infant will sleep more and seem irritable. Mouth and lips will be dry. The soft spot on the skull (fontanelle) sinks in. The infant needs to be rehydrated immediately because seizures, coma, and kidney failure threaten the life of the infant.

Hyponatremia: If parents dilute formula or feed supplemental liquids, hyponatremia—too little sodium in the blood—develops. Since the infant cannot excrete the excessive water fast enough, blood is diluted and blood electrolyte concentrations fall. Since intra-and extracellular electrolyte concentrations need to be balanced water is diffusing into the cells (osmosis). Along with all other cells, brain cells swell which increases brain pressure. Headache, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, along with muscle cramps are the first identifiable symptoms. If the hyponatremia progresses seizures, coma, and death follow.

To prevent these problems, it is essential that parents and caregivers only feed breastmilk and formula mixed according to the instructions during the first four months.

Feeding with Breastmilk in Early Care and Education Programs

Mothers may choose to have their breastfed infants fed in one of several ways when the infant is in child care including:

- mother uses her breaks to come to the child care site at feeding times to nurse her infant;

- child care provider gives the infant the breast milk that the mother has expressed on the previous day.

Follow the feeding method that the mother chooses. Feeding advice such as the use of infant formula should come from the infant’s doctor or clinic.

Expressed breastmilk needs to be stored and handled safely to keep it from spoiling. Remind mothers to label, date, and chill or refrigerate their breastmilk right after they express it. Ask mothers to bring the milk in hard plastic bottles.

Ask mothers to bring in enough breast milk to feed the infant each day. Be sure that each bottle or other container of breastmilk is labelled with the infant’s name and the date the milk was expressed. Bottles should have just the amount both you and the mother think the infant will take at each feeding. This amount will be about 2 to 4 ounces of breast milk for the younger infant. As the infant gets older, the mother can put more breastmilk in each bottle. Keep breastmilk in the refrigerator or freezer until ready to use. Breastmilk that is not frozen, should be disposed of if not eaten within 72 hours.

Thaw frozen breastmilk by running the container under cool water. Do not set breastmilk out to thaw at room temperature. Do not thaw breastmilk by heating on the stove or in a microwave.[15] See below for instructions on how to bottle-feed an infant.

Although breast milk is ideal for almost all infants, not all mothers will be able to breastfeed and some mothers should not breastfeed (including women with HIV, who are being treated for cancer, or who are taking drugs that are not safe while breastfeeding).

For more information on how to support breastfeeding in your child care centre visit Canadian Child Care Federation to view the resources sheets on this topic.

Formula Feeding

Infant formula provides a balance of nutrients. However, not all formulas are the same and there are important considerations that parents and caregivers must weigh. Standard formulas use cow’s milk as a base. They have 20 calories per fluid ounce, similar to breast milk, with vitamins and minerals added. Soy-based formulas are usually given to infants who develop diarrhea, constipation, vomiting, colic, or abdominal pain, or to infants with a cow’s milk protein allergy. Hypoallergenic protein hydrolysate formulas are usually given to infants who are allergic to cow’s milk and soy protein. This type of formula uses hydrolyzed protein, meaning that the protein is broken down into amino acids and small peptides, which makes it easier to digest.

Infant formula comes in three basic types:

- Powder that requires mixing with water. This is the least expensive type of formula.

- Concentrates, which are liquids that must be diluted with water. This type is slightly more expensive.

- Ready-to-use liquids that can be poured directly into bottles. This is the most expensive type of formula. However, it requires the least amount of preparation. Ready-to-use formulas are also convenient for travelling.

Most infants need about 2.5 ounces of formula per pound of body weight each day. Therefore, the average infant should consume about 24 fluid ounces of breast milk or formula per day. When preparing formula, caregivers should carefully follow the safety guidelines, since an infant has an immature immune system. All equipment used in formula preparation should be sterilized. Prepared, unused formula should be refrigerated to prevent bacterial growth. Caregivers should make sure not to use contaminated water to mix formula to prevent foodborne illnesses. Remember to follow the instructions for powdered and concentrated formula carefully—formula that is overly diluted would not provide adequate calories and protein, while an overly concentrated formula provides too much protein and too little water which can impair kidney function.[16]

Feeding with Formula in Early Child Care and Education Programs

Early care and education programs provide commercially prepared formulas to infants, under the direction of the family. Bottles of formula should come prepared in bottles labelled with the infant’s name and the date. Unused mixed formula should not be stored for more than 24 hours.

Bottle-Feeding (Both Expressed Breastmilk and Formula)

Always wash your hands before handling bottles or feeding the infant. Use only clean bottles, nipples, and cups. For infants that do not crawl, bottles and nipples should be sterilized. If you need to reuse them, sterilize them by boiling them in water for 5 minutes or by washing them in a dishwasher.

Warm breastmilk and formula by placing the bottle in a pan of warm water or by holding it under warm running water for a few minutes. Do not warm breastmilk or formula on the stove or in a microwave. Microwave heating causes hot spots in the milk that can burn the infant’s mouth and throat. These hot spots may stay even if you shake the bottle. And heating also destroys most of the natural substances in breast milk.

Double-check the labels on bottles before feeding to ensure the infant is getting the correct breast milk or formula. Always hold the infant when bottle feeding. Try different positions for infants who do not want to take their bottles. Some infants are happier if you feed them in the usual cradle position. Others prefer a different position. Do not prop up a bottle to feed an infant or put an infant in a crib with a bottle. Bottle propping could cause the infant to choke, tooth decay, and ear infections.

Burp by placing the infant high over your shoulder or over your knee. You can also lean the infant forward in a sitting position supported by your hands. Pat or rub the infant’s back. This puts gentle pressure on the abdomen to push extra air from the stomach.[18]

Uneaten breast milk or formula should be discarded after a feeding, as bacteria from the infant’s mouth may have made it into the bottle.

When to Feed

In the early months, infants will need to be fed “on demand”—this means that they can feed whenever they are hungry or show hunger cues. Hunger cues are unique to each infant. An infant might:

- Have a specific hunger cry

- Root or look around for food

- Suck on their hand or fingers

- Become irritable or restless

- Repeat a unique behaviour to demonstrate hunger.

When adults respond to an infant’s hunger cues, the infant can also tell how much food they want and when they are full. This feeding practice supports healthy eating habits, growth, and development later in life.[19]

Pause to Reflect

|

Some families put infants on a schedule that dictates when they eat (and even sleep)? Is this compatible with feeding on demand as described above? How might you discuss this with a family? |

Introducing Solid Foods

Infants should be breastfed or formula-fed exclusively for the first six months of life according to the WHO. (The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends breast milk or bottle formula exclusively for at least the first four months, but ideally for six months.) Infants should not consume solid foods before six months because solids do not contain the right nutrient mix that infants need. Also, eating solids may mean drinking less breast milk or bottled formula. If that occurs, an infant may not consume the right quantities of various nutrients. If parents try to feed an infant who is too young or is not ready, their tongue will push the food out, which is called an extrusion reflex.

After six months, the suck-swallow reflexes are not as strong, and infants can hold up their heads and move them around, both of which make eating solid foods more feasible.[20]

In addition, after the first six months, the breastmilk supply slowly increases after the first month. As the infant grows and requires more nutrients, the production of breastmilk amount is not sufficient anymore to provide the increasingly active infant with enough energy for optimal growth. Infants who are nursed without solids tend to drop off their growth percentile, first for weight, and if the situation is not fixed, the length drop-off will follow.

In addition, breastmilk is low in iron. This is not a problem during the first 6 months because during the last weeks of pregnancy iron stores are build in the fetus. Those iron stores tend to be depleted around the end of the 6th month and other nutritional iron sources become necessary.

Formula has sufficient amounts of iron but the liquid nature of the formula does not provide the energy density to satisfy the increasing energy needs of the active infant. The infant would need to drink lots of formula, and the infant’s stomachs are small. While solids are now introduced and the amount is steadily increasing, the American Academy of Pediatrics still recommends to keep feeding human milk, nursing or pumped, until the end of the first year. If mothers decide to stop breastfeeding or pumping milk the infant still needs formula meals until the end of the first year.

Knowing When an Infant is Ready for Solid Foods

Here are several ways you can tell that an infant is ready to eat solid foods:

· The infant’s birth weight has doubled.

· The infant can control their head and neck movements.

· The infant can sit up with some support.

· The infant can show you they are full by turning their head away or by not opening their mouth.

· The infant begins showing interest in food when others are eating.

Solid baby foods can be bought commercially or prepared from regular food using a food processor, blender, food mill, or grinder.[21] Baby food can be served at room temperature. If it is warmed, it must be stirred to distribute evenly.[22]

Portion the amount of food you intend to serve the baby (any uneaten food will need to be thrown away after a feeding) and use small amounts on an infant-sized spoon. When beginning solid foods, timing is important. To keep mealtimes positive, choose a time when the infant is happy and when you have the patience and time to focus. Offer 1 to 2 teaspoons after breast milk or formula feeding. This can increase over time to 2 to 3 tablespoons.

It is normal for infants to refuse new foods. Sometimes it can take 10 to 12 times to offer a specific food before an infant will accept it. Infants know when they have had enough and may turn their heads away. Don’t force them to keep eating.[23]

As families and caregivers introduce solids, they should feed the child only one new food at a time, to help identify allergic responses or food intolerances. An iron supplement is also recommended at this time.[24]

Foods to Avoid for Infants

· Never give honey to infants. It may contain bacteria that can cause botulism, a rare, but serious illness.

· Do not give infants cow’s milk until they are 1 year old. Before age 1, they have a difficult time digesting cow’s milk.

· Avoid foods with added salt or sugar.

· Do not give infants egg white until after they are 1 (egg yolks 3-4 per week are okay)[25]

Transition Process to Family Meals [26]

Feeding reflexes during the first four months: Infants are born with reflexes that prime them for breastfeeding. These feeding reflexes include the rooting reflex and the suck-and-swallow reflex. If an infants cheek is touched, for example, by a nipple of the breast or bottle the infant turns the head towards it. Once the nipple touches the inside of the mouth the suck-and-swallow reflex sets in and the infant automatically takes in milk and swallows.

Rooting reflex and suck/swallow reflex:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=b0CLcNtOOEQ%3Ffeature%3Doembed%26rel%3D0

Tongue thrust reflex:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=oXiCIGcz8ww%3Ffeature%3Doembed%26rel%3D0

Phasic bite reflex:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=nzpgXDvgB7s%3Ffeature%3Doembed%26rel%3D0

In addition, the extrusion (tongue thrust) and gag reflex prevents the infant from choking on solid or semi-solid foods, or non-nutritive items that make it into the mouth of the infant. If the tongue is touched by a semisolid or solid object, the tongue will push forward, and hopefully, push the object out of the mouth. If the object bypasses the extrusion reflex, the gag reflex makes sure it is not swallowed.

With those feeding reflexes in place th infant will me a natural when it comes to feeding from the breast (or bottle).

Fine-motor skills: Developing fine-motor skills are first visible when a bottle fed infant “helps” feeding by putting a hand on the bottle during the second or third month. Keep in mind that becoming a helper does not mean that the infant is ready for a solid spoon. This transitions into the ability to hold the bottle around the six month mark. At the same time the infant has the ability to drink from a sippy cup, which should be encouraged to start the transition away from the bottle. Bottle feeding should stop with the first birthday.

During the 5th or 6th month the infant has developed a pincer grasp that will allow them to pick up a small piece of melt-in-the-mouth food, such as a (sugar-free) cheerio, and place it in the mouth.

These various changes allow the infant to ease into complementary feedings, which involves the introduction of semi-liquid solid foods and small pieces of soft food.

Learning to Self-Feed

With the introduction of solid foods, young children begin to learn how to handle food and how to feed themselves. At six to seven months, infants can use their whole hand to pick up items (this is known as the palmer grasp). They can lift larger items, but picking up smaller pieces of food is difficult. At eight months, a child might be able to use a pincer grasp, which uses fingers to pick up objects.[27]

Serve food that is soft and mashed. Cut food into small pieces (cubes no larger than 1/4 inch) or thin slices that your baby can easily chew and swallow. Avoid high-risk choking foods such as small, slippery foods; dry foods that are hard to chew or sticky; and tough foods.[28]

Finger Foods

Here are some good food choices for self-feeding children:

· Soft-cooked vegetables

· Washed and peeled fruits

· Graham crackers

· Melba toast

· Noodles

· Soft-cooked vegetables

· Washed and peeled fruits

· Graham crackers

· Melba toast

· Noodles

Here are foods to AVOID as they are a choking hazard:

· Apple chunks or slices

· Grapes

· Berries

· Raisins

· Dry flake cereals

· Hot dogs

· Sausages

· Peanut butter

· Popcorn

· Nuts

· Seeds

· Round candies

· Raw vegetables[29]

To minimize choking, ensure that infants are seated while eating. If using a high chair, make sure to use the safety straps.[30]

After the age of one, children slowly begin to use utensils to handle their food. Unbreakable dishes and cups are essential, since very young children may play with them or throw them when they become bored with their food.[32]

Eating From a Spoon Skills [33]

The feeding reflexes make drinking from the breast or a bottle during the first six months automatic. No special skills are needed.

Eating with a spoon is different. The infant needs to develop fine motor skills and some of the early feeding reflexes need to wane. If parents offer a spoon with semi-liquid food to a 3-month-old infant, the touching of the lips will start a sucking motion. Since the spoon is solid the tongue thrust reflex (or gag reflex depending on how far the spoon is stuck into the mouth) will set in and the tongue will push against the spoon. This makes more of a mess than feeding the infant.

Therefore, the suck and swallow, tongue thrust, and gag reflex need to wane to allow the spoon into the mouth. The phasic bite reflex will remain for a while longer. This reflex allows to transport a bolus from the front to the back of the mouth. This reflex is initially essential to remove pureed food from the spoon transport it to the back of the mouth and then swallow.

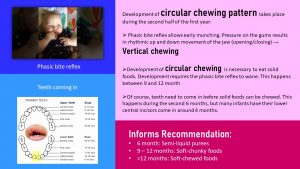

Progression to Chewing Soft Food [34]

After a pincer grasp develops, infants can pick up small melt-in-the-mouth foods such as an infant cracker or cheerios—both without added sugar—and place it into their mouth. When the food touches the gums, the phasic bite reflex kicks in, a vertical chewing motion is started. The same motion can be seen when the infant is fed purees with a spoon. This early munching practices chewing, transporting food to the back of the mouth, and swallowing. This works for soft foods—first chunky, then in pieces—but is not really effective for chewing more solid foods.

Transitioning to the family table with chewy foods requires the development of a circular chewing pattern. Try to chew a piece of chicken with a vertical motion, no lateral motion allowed. Not possible. Between the 9th and 12th month, the phasic bite reflex vanishes allowing for a combined vertical and lateral motion. The child will still need to practice a lot to graduate to a piece of steak, but the stage is set.

Of course, in addition to the vanishing reflexes the infant needs to grow some teeth. The first set of teeth coming in are the lower central incisors giving the infant that cute look. Before those teeth become useful—instead of chomping down while breastfeeding—several more teeth need to come in—especially the molars. This development stretches all through the second year and part of the third. This lack of a full set of molars is the reason while the toddler will still have a tough time chewing harder food and need to be supplied with smaller pieces of food.

Overall, the continuous, progressive development during the first year will allow the infant to develop eating skills:

| Age | Infant Eats | Developmental Milestone |

|---|---|---|

| 0-6 Months | Exclusively breastmilk or formula | Feeding reflexes in place |

| 6 – 9 months | Breastmilk/formula, semi liquid foods, melt-in-the-mouth food pieces | Rooting, suck and swallow reflex vanishes, phasic bit reflex in place, pincer grasp develops |

| 9 – 12 months | Breastmilk/formula + soft-chunky transitioning to soft pieces of food | Vertical chewing due to phasic bite reflex develops into circular chewing when reflex vanishes

Teeth coming in |

The infographic below shows some developmental highlights on the left and the feeding development on the right. Note that some developmental stages and feeding correspond. [35]

Supporting Infant Nutrition

Nutrition during the first year of life is really important. While babies who are breastfed for at least 6 months are more likely to have a healthy weight as they grow up, mothers often report that breastfeeding is harder than they thought. Mothers may be more likely to stop breastfeeding if they feel unsupported and have nowhere to turn for help. Families that choose not to or cannot breastfeed have questions and need support to feed their infants in a healthy and safe way, too. Babies should be ready to start eating simple solids around 6 months. Babies who start eating solid foods too early are more likely to have weight problems as children and adults.[36]

Early care and education programs can support infant nutrition with the following practices:

- All food brought from home should be labelled with the child’s name and date.

- Part of the care plan that families share with their program and that is updated regularly, should be instructions for feeding. Families should determine how and what their infant is fed (as long as it complies with licensing).

- Support parents with materials on providing optimal nutrition for their infant (such as the tips just listed).

- Be supportive of mothers who are breastfeeding. For mothers who can come to nurse, provide a space conducive to that. Ensure the breastmilk that is brought to the program is properly labelled, stored, and prepared.

- For infants that are formula-fed, ensure that the formula is prepared according to the label (or doctor’s instructions).

- Hold all infants during bottle feedings. Not only does this keep them safe, but it is also valuable one-on-one time (caregiving routines are the heart of the infant/toddler curriculum).

- Follow the cues of the infant you are feeding (when they are hungry and full).

- When feeding pureed baby food, use a small spoon and make sure you transfer food from a jar into a dish and throw away any uneaten food.

- Have appropriate seating available for infants that are beginning to self-feed (high chairs, booster seats, or enclosed small chairs at a low table)

- Provide unbreakable dishes to serve food to self-feeding infants.

Engaging Families in Supporting Their Infant’s Nutrition

Here are tips you can share with families

- If breastfeeding is harder than you thought it would be you are not alone!

- Lots of people say that breastfeeding just comes “naturally” but for many moms, it doesn’t.

- Going back to work and wanting to get back into a normal family routine can make it hard to stick with breastfeeding. Using a breast pump can help ensure your baby still gets the best nutrition.

- If you need support or help at any time while you are breastfeeding call 1-800-994-9662 (the National Breastfeeding Hotline) for free breastfeeding support.

- Don’t use pillows or other objects to hold a bottle for your baby. This makes it hard for her to spit out the bottle when she’s done – it can cause her to keep eating after she’s full.

- Make sure you take the bottle away if your baby falls asleep. If you let the baby keep the bottle in her mouth when he’s sleeping, formula can stay in her mouth and can damage his teeth or cause her to choke.

- Stick with ONLY breast milk or formula for feeding your baby until she is 6 months old. Unless your doctor tells you something different, adding cereal to a baby’s bottle adds extra calories to her diet that she doesn’t need.[37]

- Infants are usually ready to eat solid foods at about 6 months of age.

- If you introduce one new food at a time, you will be able to identify any foods that cause allergies in your baby.[38]

- Start solid feedings with iron-fortified baby cereal mixed with breast milk or formula. Mix it with enough milk so that the texture is very thin. Start by offering the cereal 2 times a day, in just a few spoonfuls.

- You can make the mixture thicker as your baby learns to control it in their mouth.

- You can also introduce iron-rich pureed meats, fruits, and vegetables. Try green peas, carrots, sweet potatoes, squash, applesauce, pears, bananas, and peaches.

- Some dietitians recommend introducing a few vegetables before fruits. The sweetness of fruit may make some vegetables less appealing.

- The amount your child eats will vary between 2 tablespoons (30 grams) and 2 cups (480 grams) of fruits and vegetables per day. How much your child eats depends on their size and how well they eat fruits and vegetables.[39]

Feeding Toddlers

Major physiological changes continue into the toddler years. Unlike in infancy, the limbs grow much faster than the trunk, which gives the body a more proportionate appearance. Their physical growth and motor development are slow compared to the progress they made as infants. The toddler years pose interesting challenges for parents or other caregivers, as children learn how to eat on their own and begin to develop personal preferences. However, with the proper diet and guidance, toddlers can continue to grow and develop at a healthy rate.

The energy requirements for ages two to three are about 1,000 to 1,400 calories a day. In general, a toddler needs to consume about 40 calories for every inch of height. For example, a young child who measures 32 inches should take in an average of 1,300 calories a day. However, the recommended caloric intake varies with each child’s level of activity. Toddlers require small, frequent, nutritious snacks and meals to satisfy energy requirements. The amount of food a toddler needs from each food group depends on daily calorie needs.

Forty-five to 65% of their daily caloric intake should come from carbohydrates. Protein should make up 5 to 20% of their daily calories. And fat should make up 30 to 40% of their daily intake. Essential fatty acids are vital for the development of the eyes, along with nerve and other types of tissue. However, toddlers should not consume foods with high amounts of trans fats and saturated fats.

As a child grows bigger, the demands for micronutrients increase. These needs for vitamins and minerals can be met with a balanced diet, with a few exceptions. According to the Canadian Paediatric Society, toddlers and children of all ages need 600 international units of vitamin D per day. Vitamin D-fortified milk and cereals can help to meet this need. However, toddlers who do not get enough of this micronutrient should receive a supplement. Pediatricians may also prescribe a fluoride supplement for toddlers who live in areas with fluoride-poor water. Iron deficiency is also a major concern for children between the ages of two and three.[41]

Self-Feeding

As children grow older, they enjoy taking care of themselves, which includes self-feeding. During this phase, it is important to offer children foods that they can handle on their own and that helps them avoid choking and other hazards. Examples include fresh fruits that have been sliced into pieces, orange or grapefruit sections, peas or potatoes that have been mashed for safety, a cup of yogurt, and whole-grain bread or bagels cut into pieces. Even with careful preparation and training, the learning process can be messy. As a result, parents and other caregivers can help children learn how to feed themselves by providing the following:

- small utensils that fit a young child’s hand

- small cups that will not tip over easily

- plates with edges to prevent food from falling off

- small servings on a plate

- highchairs, booster seats, or small enclosed chairs to reach a low table[42]

Feeding Challenges in the Toddler Years

During the toddler years, parents may face a number of problems related to food and nutrition. Possible obstacles include difficulty helping a young child overcome a fear of new foods, or fights over messy habits at the dinner table. Even in the face of problems and confrontations, parents and other caregivers must make sure their preschooler has nutritious choices at every meal. For example, even if a child stubbornly resists eating vegetables, parents should continue to provide them. Before long, the child may change their mind, and develop a taste for foods once abhorred. It is important to remember this is the time to establish or reinforce healthy habits.

Nutritionist Ellyn Satter states that feeding is a responsibility that is split between parent and child. According to Satter, parents are responsible for what their infants eat, while infants are responsible for how much they eat. In the toddler years and beyond, parents are responsible for what children eat, when they eat, and where they eat, while children are responsible for how much food they eat and whether they eat. Satter states that the role of a parent or a caregiver in feeding includes the following:

- selecting and preparing food

- providing regular meals and snacks

- making mealtimes pleasant

- showing children what they must learn about mealtime behaviour

- avoiding letting children eat in between meal- or snack-times

You are likely to notice a sharp drop in their child’s appetite. Children at this stage are often picky about what they want to eat. They may turn their heads away after eating just a few bites. Or, they may resist coming to the table at mealtimes. They also can be unpredictable about what they want to consume for specific meals or at particular times of the day. Although it may seem as if toddlers should increase their food intake to match their level of activity, there is a good reason for picky eating. A child’s growth rate slows after infancy, and toddlers ages two and three do not require as much food.[44]

Establishing healthy meal routines is an important step in healthy toddler development. Ideally, mealtimes should take place at regular times, at a table with limited distraction, and children should be encouraged to feed themselves with adult support as needed.[45] Best practices in early care and education include creating positive meal and snack times that are served family-style with adult modeling eating balanced nutrition.

Engaging Families in Supporting Their Toddler’s Nutrition

Here are tips you can share with families:

· Serving sizes for toddlers are much smaller than serving sizes for adults.

· A typical serving size for a toddler drink is 4-6 ounces. Water and milk are the best choices for toddlers

· Your toddler (and you too!) needs food from all five of the food groups—grains, protein, vegetables, fruit, and dairy. Try offering a variety of foods from these groups at meals and snacks.

· Your toddler may eat more some days and less on others. Don’t worry, this is normal! Keep offering regularly scheduled meals and snacks.

· Allow your toddler to tell you when she is full. This teaches them to listen to their body for signs of hunger or fullness.

· Try using child-size plates, bowls, and utensils for “right-size” portions for your toddler. Using child-size utensils also makes it easier for your toddler to eat.

· Encourage toddlers to drink from cups and avoid the use of bottles or sippy cups.

· Limit distractions during meal and snack times to allow your toddler to enjoy the food. Turn off the TV and sit at a table.

· Toddlers get hungry between meals. Snack time is a great chance to feed your toddler healthy foods (like fruits and veggies).

· Remember to have a start and end time for snack time. Toddlers should not be snacking (or grazing) all day.[46]

Feeding Preschoolers

Children’s attitudes and opinions about food deepen. They not only begin taking their cues about food preferences from family members, but also from peers and the larger culture. This time in a child’s life provides an opportunity for families and other caregivers to reinforce good eating habits and to introduce new foods into the diet while remaining mindful of a child’s preferences. Adults should also serve as role models for their children, who will often mimic their behavior and eating habits.[47]

In early childhood, children should still get 45-65% of their daily calories from carbohydrates. Carbohydrates high in fiber should make up the bulk of intake. Their intake of protein increases to 10–30% of their daily calories to support muscle growth and development. High levels of essential fatty acids are needed to support growth (although not as high as in infancy and the toddler years). As a result, the daily recommendation for fat is 25–35% of their daily calories. And they should get 17–25 grams of fiber per day.

Their micronutrient needs should be met with foods first. Families and caregivers should select a variety of foods from each food group to ensure that nutritional requirements are met. Because children grow rapidly, they require foods that are high in iron, such as lean meats, legumes, fish, poultry, and iron-enriched cereals. Adequate fluoride is crucial to support strong teeth. One of the most important micronutrient requirements during childhood is adequate calcium and vitamin D intake. Both are needed to build dense bones and a strong skeleton. Children who do not consume adequate vitamin D should be given a supplement of 10 micrograms (400 international units) per day.[49]

Feeding Challenges in the Preschool Years

Picky eating is typical for many preschoolers. It’s simply another step in the process of growing up and becoming independent. As long as a preschooler is healthy, growing normally, and has plenty of energy, they are most likely getting the nutrients they need.

Typical Picky Eating Behaviors

Many children will show one or more of the following behaviours during the preschool years. In most cases, these will go away with time.

- Refusal of a food based on a certain colour or texture. For example, they could refuse foods that are red or green, contain seeds, or are squishy.

- Only eating a certain type of food. A preschooler may choose 1 or 2 foods they like and refuse to eat anything else.

- “Wasting” of time at the table and seeming interested in doing anything but eating.

- Unwillingness to try new foods. It is normal for a preschooler to prefer familiar foods and be afraid to try new things.[50]

Helping Families Cope with Picky Eating

Picky eating is temporary. If adults don’t make it a big deal, it will usually end before school age. The following tips are tips to help deal with picky eating behavior positively.

· Let your kids be “produce pickers.” Let them pick out fruits and veggies at the store.

· Have your child help you prepare meals. Children learn about food and get excited about tasting food when they help make meals. Let them add ingredients, scrub veggies, or help stir.

· Offer choices. Rather than ask, “Do you want broccoli for dinner?” ask “Which would you like for dinner, broccoli or cauliflower?”

· Enjoy each other while eating family meals together. Talk about fun and happy things. If meals are times for family arguments, your child may learn unhealthy attitudes toward food.

· Offer the same foods for the whole family. Serve the same meal to adults and kids. Let them see you enjoy healthy foods. Talk about the colors, shapes, and textures on the plate.[51]

· Make food fun

· Cut food into fun and easy shapes with cookie cutters.

· Encourage your child to invent and help prepare new snacks.

· Name a food your child helps create.[52]

· Focus on the meal and each other. Your child learns by watching you. Children are likely to copy your table manners, your likes and dislikes, and your willingness to try new foods.

· Offer a variety of healthy foods. Let your child choose how much to eat. Children are more likely to enjoy a food when eating it is their own choice.

· Let your children serve themselves. Teach your children to take small amounts at first. Let them know they can get more if they are still hungry.[53]

Trying New Foods

It is normal for children to reject foods they have never tried before. Here are some tips to get preschoolers to try new foods:

- Small portions, big benefits. Let children try small portions of new foods that you enjoy. Give them a small taste at first and be patient with them.

- Offer only one new food at a time and ideally with a favoured food. Offering many new foods all at once could be too much for children.

- Be a good role model. Try new foods yourself. Describe their taste, texture, and smell to the children.

- Offer new foods first when children are most hungry.

- Offer new foods many times. It may take up to a dozen tries for a child to accept a new food.[54]

Pause to Reflect

|

Think back to your childhood. Were you a picky eater or more adventurous? Why do you think that it was? How did your caregivers respond to your eating preferences? Do you have similar preferences now or have you expanded your tastes/preferences? |

Feeding School-Aged Children

While calorie needs go up as children get older, until around age 9 (or the beginning of puberty), nutritional needs for school-aged children are very similar to preschoolers. Once puberty begins, there is a period of rapid growth as girls grow 2-8 inches and boys grow 4-12 inches

School-aged children should still get 45-65% of their daily calories from carbohydrates. Carbohydrates high in fibre should make up the bulk of that. Their intake of protein remains at 10–30% of their daily calories to support muscle growth and development. And the daily recommendation for fat also remains at 25–35% of their daily calories.

A few micronutrients take on added importance, especially at the beginning of puberty. These include vitamins, D, K, and B12, calcium, and iron. Whenever possible these additional micronutrient needs should be met with dietary choices and not supplements (with the exception of iron).[55]

Meals and Snacks in School-Aged Care Programs

On school days, children who are in care before school may need to be fed breakfast (if they did not eat at home or will not be eating at school). After school, they will need substantial, healthy snacks. On full days of care, they will need breakfast, lunch, and a snack.

Follow the menu planning advice in Chapter 15. Involve the children in menu planning and food preparation whenever possible and see which of the suggestions in the following feature for families might also be incorporated into the classroom.

Figure 14.9 – These 9-year-olds learned the knife skills to help prepare this snack of fruit.[56]

Choosemyplate.gov offers some fun ideas for families to teach their children about healthy eating and engage the whole family in making healthy choices. Some of these include:

Making Mealtimes Fun

|

Feeding Children with Disabilities

Some disabilities and other exceptional needs may affect children’s nutrition. For example,

- children with cerebral palsy or cystic fibrosis may have different caloric needs

- children with celiac disease or irritable bowel syndrome may have dietary restrictions

- children with cleft lip or palate may have physical difficulties with eating

- children on the autism spectrum may have strong food preferences or aversions

Because each child’s specific needs will vary, early care and education programs should work closely with families, and medical providers as needed, to ensure that they understand and can meet the nutritional and feeding needs of the individual child (not a generalization or assumption about the child might need based on a diagnosis or label).

Nutrition policies and practices should be created to be inclusive of children with special needs. Some general considerations early care and education programs and schools should make to ensure that all children’s nutritional needs are met and that all children experience positive meal and snack times include:

- Ensure that the spaces in which children eat and access to drinking water are fully accessible to all children, including those with mobility impairments (and if needed, assistive devices should be provided).

- Staff should be trained to provide for children who may have additional or differing nutritional or feeding needs so they can work effectively and comfortably with all children.

- Follow any dietary restrictions.[61]

Summary

Early care and education programs can provide for all children’s nutrition when they understand

- the general changes children have in nutritional needs as they mature,

- common challenges across the different stages of development, and

- strategies that foster positive meal and snack times at each age stage, and

- the fact that children may have diverse and unique nutritional needs

Programs also play an important role in children’s nutrition by empowering families by providing support, information, and resources as they make decisions about how to feed their children.

Resources for Further Exploration

· Head Starts’ Growing Healthy guide: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/growing-healthy-flipchart.pdf

· Ellyn Satter Institute: https://www.ellynsatterinstitute.org/how-to-feed/child-feeding-ages-and-stages/

· USDA’s Breastfeeding: Why Not Give It a Try?: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/breastfeeding-why-not-give-it-a-try-eng.pdf

· Toddler Nutrition and Health Resource List: https://www.nal.usda.gov/sites/default/files/fnic_uploads//toddler.pdf

· Resources on MyPlate.gov:

· Daily Food Plan: https://choosemyplate-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/audiences/HealthyEatingForPreschoolers-MiniPoster.pdf

· Preschoolers: https://www.choosemyplate.gov/browse-by-audience/view-all-audiences/children/health-and-nutrition-information

· Kids: https://www.choosemyplate.gov/browse-by-audience/view-all-audiences/children/kids

· Healthy Beverages in Early Care and Education: https://cchp.ucsf.edu/content/healthy-beverages-early-care-education

· The CDC Guide to Strategies to Support Breastfeeding Mothers and Babies: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/resources/toolkits.html

· KidsHealth From Nemours Nutrition & Fitness Center: https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/nutrition-center/?WT.ac=p-nav-nutrition-center

· USDA’s Accommodating Children with Special Dietary Needs in the School Nutrition Programs: https://www.fns.usda.gov/accommodating-children-special-dietary-needs-school-nutrition-programs

· USDA’s Nutrition Curricula: https://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/curricula-and-lesson-plans

· Golisano Children’s Hospital’s Special Diets for Nutritional Special Needs: https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/childrens-hospital/nutrition/diets.aspx

References

- Growth and development during the first year of life, by Sabine Zempleni and Synney Christensen, Nutrition Through the Live Cycle, sed with permission -Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDervatives 4.0. ↵

- Growth and development during the first year of life, by Sabine Zempleni and Synney Christensen, Nutrition Through the Live Cycle, sed with permission -Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDervatives 4.0. ↵

- Routine Checkups, Healthlink BC, Government of BC, in the public domain ↵

- Growth and development during the first year of life, by Sabine Zempleni and Synney Christensen, Nutrition Through the Live Cycle, sed with permission -Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDervatives 4.0. ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- The Important Role of Staff in Breastfeeding Education and Support by Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center is in the public domain ↵

- Baby sucking breast of mom, PickPik, in the public domain ↵

- Breastfed Babies Welcome Here! by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service is in the public domain ↵

- Pickpik, baby sucking breast of mom, in the public domain ↵

- Nellis Child Development Center II by Staff Sgt. Taylor Worley (USAF) is in the public domain ↵

- Growth and development during the first year of life, by Sabine Zempleni and Synney Christensen, Nutrition Through the Live Cycle, used with permission -Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDervatives 4.0. ↵

- Breastfed Babies Welcome Here! by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service is in the public domain ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image by Ben Kerckx on Pixabay ↵

- Breastfed Babies Welcome Here! by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service is in the public domain ↵

- Healthy Feeding from the Start: A Resource for Expectant Families by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Tips for Keeping Infants and Toddlers Safe: A Developmental Guide for Home Visitors – Mobile Infants by Early Head Start National Resource Center is in the public domain ↵

- Introducing Complementary Foods: Feeding from Around 6 Months by Queensland Government is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Feeding Patterns and Diet – Children 6 Months to 2 Years by MedlinePlus is in the public domain ↵

- Growth and development during the first year of life, by Sabine Zempleni and Synney Christensen, Nutrition Through the Live Cycle, sed with permission -Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDervatives 4.0. ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Tips for Keeping Infants and Toddlers Safe: A Developmental Guide for Home Visitors – Mobile Infants by Early Head Start National Resource Center is in the public domain ↵

- Feeding Patterns and Diet – Children 6 Months to 2 Years by MedlinePlus is in the public domain ↵

- Tips for Keeping Infants and Toddlers Safe: A Developmental Guide for Home Visitors – Mobile Infants by Early Head Start National Resource Center is in the public domain ↵

- Image by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Growth and development during the first year of life, by Sabine Zempleni and Synney Christensen, Nutrition Through the Live Cycle, sed with permission -Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDervatives 4.0. ↵

- Growth and development during the first year of life, by Sabine Zempleni and Synney Christensen, Nutrition Through the Live Cycle, sed with permission -Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDervatives 4.0. ↵

- Transitioning to Solids and Family Meals, by Sabine Zempleni, Nutrition Through the Live Cycle, sed with permission -Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDervatives 4.0. ↵

- Growing Healthy by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain ↵

- Growing Healthy by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain ↵

- Infant and Newborn Nutrition by MedlinePlus is in the public domain ↵

- Feeding Patterns and Diet – Children 6 Months to 2 Years by MedlinePlus is in the public domain ↵

- Growing Healthy by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Feeding Your Toddler by Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center is in the public domain ↵

- Feeding Your Toddler by Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center is in the public domain ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Serving Spoons and Healthy Habits by Mallory Feeney is in the public domain ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Tips for Picky Eaters by the USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion is in the public domain ↵

- Tips for Picky Eaters by the USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion is in the public domain ↵

- Healthy Tips for Picky Eaters by the USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion is in the public domain ↵

- Healthy Eating for Preschoolers by the USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion is in the public domain ↵

- Tips for Picky Eaters by the USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion is in the public domain ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Schriever Children Learn New Skills at Cooking Camp by 2nd Lt. Idalí Beltré Acevedo (USAF) is in the public domain ↵

- Kids Food Critic Activity by the USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion is in the public domain ↵

- MyPlate Grocery Store Bingo by the USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion is in the public domain ↵

- MyPlate, MyWins for Families by the USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion is in the public domain ↵

- Cleft Nurser Mead Johnson by King97tut is in the public domain ↵

- Are School Feeding Programs Prepared to Be Inclusive of Children with Disabilities? by Sergio Meresman and Lesley Drake is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵