Chapter 7: Promoting Good Health and Wellness

Introduction

Environmental and Social Factors That Impact Health

Social Determinants of Health

The Five Most Relevant Social Determinants of Health

Health Promotion

Mental Health Promotion

Health Promotion in Early Childhood Settings

Children’s Records

Staff Records

The Importance of Keeping Staff Healthy

Occupation Health

Preventing Musculoskeletal Injuries

Working with Art and Cleaning products

Psychological well-being

Daily Health Checks

Conducting a Daily Health Check

Dental Hygiene

Sleep Hygiene

The Culture of Sleep and Child Care

Developmental and Health Observations

Screening

Vision Screening

Hearing Screening

Lead Screening

Social, Emotional and Behavioural Screening

Screening Resources for Saskatchewan

Summary

Resources

References

Chapter 7 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Summarize what goes into child and staff health records.

- Describe the process of daily health checks.

- Explain good dental hygiene practices in the classroom.

- Discuss the importance of sleep.

- Identify different screenings that early care and education programs can implement.

- Relate the importance of developmental screening.

- Recall ways to engage families in the screening process.

Introduction

What is Health?

Health is a journey throughout your life. It’s a quest for meeting your own needs and goals. Health also means the ability to be resilient in times of change. You’ll have your ideas of the meaning of health. Similarly, quality of life is unique to you and your values, background and experiences. Quality early childhood education programs contribute to the well-being of young children and their families.

The World Health Organization (WHO), is the “United Nations agency that connects nations, partners and people to promote health, keep the world safe and serve the vulnerable – so everyone, everywhere can attain the highest level of health” (World Health Organization [WHO], 2023)1. In their original, 1948 constitution, the WHO defined health as:

In 1986 the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, organization enhanced the term health to include the following statement:

“the extent to which an individual or group is able, on the one hand, to identify and to realize aspirations and satisfy needs, and on the other, to change or cope with the environment. Health is therefore seen as a resource for everyday life, not the objective of living. It is a positive concept encompassing social and personal resources as well as physical capacities” (WHO, 2005 pg. 3).

This refinement of the definition signifies a move from merely viewing Health as absent of “disease or infirmity” to including the vital aspects of mental and social well-being. Without mental and social well-being can an individual and/or group ever truly be healthy?

With health clearly defined social researchers, scientists and lawmakers could move forward to establish policies that uphold the ideology of WHO and each State (Countries) involved and ultimately benefit mankind. The acknowledgment of the importance of mental and social well-being paved the way for participating states to create public policies that uphold these beliefs.

Environmental and Social Factors That Impact Health

Now that we have a better understanding of what the definition of health is, we can now look at how different factors affects the health of the children and their families that we work with. The majority of the work you’ll do with children and families is based on health and wellness. If you, the children and their families are not healthy, all other aspects of life and development are affected.

Early childhood, particularly the first 5 years of life, impacts long–term social, cognitive, emotional, and physical development. Healthy development in early childhood helps prepare children for the educational experiences of kindergarten and beyond. Early childhood development and education opportunities are affected by various environmental and social factors, including:

- Early life stress

- Socioeconomic status

- Relationships with parents and caregivers

- Access to early education programs

Early life stress and adverse events can have a lasting impact on the mental and physical health of children. Specifically, early life stress can contribute to developmental delays and poor health outcomes in the future. Stressors such as physical abuse, family instability, unsafe neighbourhoods, and poverty can cause children to have inadequate coping skills, difficulty regulating emotions, and reduced social functioning compared to other children their age.

Additionally, exposure to environmental hazards, such as lead in the home, can negatively affect a child’s health and cause cognitive developmental delays. Research shows that lead exposure disproportionately affects children from minority and low–income households and can adversely affect their readiness for school or their “…ability to succeed both academically and socially in a school environment” (Ferguson et al., 2007, pg 701).

The socioeconomic status of young children’s families and communities also significantly affects their educational outcomes.  Specifically, poverty has been shown to influence the academic achievement of young children negatively. Research shows that, in their later years, children from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to need special education, repeat grades, and drop out of high school. Children from communities with higher socioeconomic status and more resources experience safer and more supportive environments and better early education programs (Ferguson et al. 2007).

Specifically, poverty has been shown to influence the academic achievement of young children negatively. Research shows that, in their later years, children from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to need special education, repeat grades, and drop out of high school. Children from communities with higher socioeconomic status and more resources experience safer and more supportive environments and better early education programs (Ferguson et al. 2007).

It’s a domino effect. Evidence shows that experiences in childhood are extremely important for a child’s healthy development and lifelong learning. How a child develops during this time affects future cognitive, social, emotional, language, and physical development, which in turn influences school readiness and later success in life. Research on many adult health and medical conditions points to pre-disease pathways that have their beginnings in early and middle childhood.

Social Determinants of Health

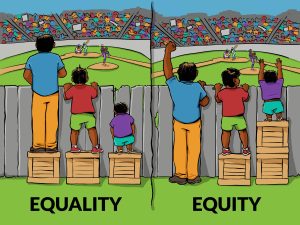

We will now look at twelve (12) common social determinants of health (SDH). If any of the determinants of health are challenged or lacking for children and families, then health and safety issues arise. One of our many roles as early childhood educators is to promote health. To do this we need to understand some of the factors or SDH that may stand in the way of the children we care for and their families might face and how they impact overall health.

The environmental and social factors that impact children and their family’s health are known as social determinants of health (SDH). If you google social determinants of health you will find that a list of SDH will differ slightly from source to source.

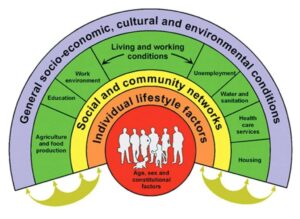

In their groundbreaking work, Goran Dahlgren and Margaret Whitehead (1991) put forth the “Rainbow Model” of the determinants of health. Their focus was on health policies, but in the process created a model that goes beyond the healthcare system (Dahlgren & Whitehead, 2021). In general terms, SDH falls into 4 layers that influence an individual’s health. Dahigren and Whitehead’s (1991) model of SDH helps to visually explain how health inequities impact the overall health of individuals.

In their model, Dahlgren & Whitehead (1991) illustrated the main influences on health. The first layer is the outer layer is the general socio-economic, cultural and environmental conditions layer and it depicts the major structural environments such as government policies, the economy and agreements between countries (Dahlgren & Whitehead, 1991). The 2nd layer is the material and social conditions and they incorporate everything related to a person’s life including where they live and work. The 3rd layer is the social and community network – this layer runs on mutual support from family, friends and the community. The 4th layer is the individual lifestyle which represents the actions and choices made by the individual. In the centre is an individual’s genetic makeup (sex, age etc.). These factors are fixed and we have little control over them (Dahlgren & Whitehead, 1991).

Twelve (12) factors influence your overall health and maintain health throughout your life. The twelve social determinants of health (SDH) are identified in the interactive image below, tap on the plus sign (+) to see information about each of the 12 SDHs. As you are reading, think about if and how each of the SDHs impacts you. You’ll notice that each SDH may have more impact at different times in your life.

Watch the following video outlining the health inequities in Canada. As you watch, think about what your role could be in supporting children and young families in trying to make health more accessible to all.

The five most relevant Social Determinants

Now that we have a general understanding of SDH, you are probably thinking why do I need to know this? You need to know about SDH, so you can identify where a child and their family may be struggling and provide resources. A child is more than what you can see. As we just learned there are many unseen factors (SDH) that impact children and their families. These factors are not necessarily visible and they differ from child to child and their family. As stated above “the majority of the work you’ll do with children and families is based on health and wellness”, to do this you need to get to know the families and their unique situations. Above it mentions how SDH acts like dominoes falling, you as an early childhood educator have an opportunity to interrupt the cascade and redirect a child and their family onto a different path in life, which may have better outcomes.

The five (5) most relevant SDHs you will encounter in your work as an early childhood educator and see how we can improve the health outcome for a child and their family.

-

-

Healthy Child Development

-

Income and Social Status

-

Education and Literacy

-

Social Support Networks

-

Culture

-

Health Promotion

According to the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, health promotion is defined as:

“Health promotion is the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health. To reach a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, an individual or group must be able to identify and to realize aspirations, to satisfy needs, and to change or cope with the environment. Health is therefore, seen as a resource for everyday life, not the objective of living. Health is a positive concept emphasizing social and personal resources, as well as physical capacities. Therefore, health promotion is not just the responsibility of the health sector, but goes beyond healthy life-styles to well-being”[1]

So what does that mean for you as an educator?

As an educator, you must promote and model health promotion, in order to accomplish this you must be able to:

-

- Identify and realize individual aspirations

- Satisfy individual needs

- change or manage the environment

- focus on individual strengths

Mental Health Promotion

Mental health is a growing concern in Canada, especially after Covid lockdowns. The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) defines mental health promotion as “the capacity of each and all of us to feel, think, act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face. It is a positive sense of emotional and spiritual well-being that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, interconnections and personal dignity”[2]

The video below is from the Government of Canada celebrating Canada’s 2023, mental health week. In the video, the Honourable Carolyn Bennett talks about sharing stories about mental health to break down the stigma. She also discusses the importance of mental health literacy.

Health Promotion in Early Childhood Setting

Healthy development continues to support learning throughout childhood and later life. “Health in the earliest years…lays the groundwork for a lifetime of well-being…”[1] To promote the health of children in early care and education programs, it’s important to keep records of both children’s and staff’s health. Programs can support children’s oral health and healthy sleep habits. And they can help identify developmental and health concerns with screening.

Children’s Records

“The health and safety of individual children requires that information regarding each child in care be kept and available when needed. Children’s records require to have the following information:

- child’s name and date of birth

- Names, addresses and telephone information of the child’s parents, emergency contacts and medical practitioner

- List of any allergies, illness or other medical conditions disclosed by the family or their medical practitioner

- The child’s immunization status

- Any medical authorization from parents and record of medication administered

- permission for both excursions that involve or do not involve transportation of a child

- Any reports of an injury or unusual or unexpected occurrence involving a child

- Parental agreement for childcare services.

Child Care Regulation. Section 36 – Children’s records:

Section 36 (1) A licensee must:

- Kept record of each child in attendance

- Be retained for 2 years after the child stops attending the facility.

- The information must be updated as changes occur.

- Records can only be seen by staff who need the information in order to provide care for that child.

- Children’s records must be stored in a locked cabinet, drawer or box.

Review the Saskatchewan Child Care Licensee Manual Section 36: Children’s Records for what must be retained in every child’s file; what needs to be completed as needed; and what is optional.

Section 36 (2)Records required include:

- Child’s name and date of birth

- names, addresses and telephone numbers of a child’s parent(s) and that of the parent-approved contact person in cases where the parent is unavailable.

- name, address and telephone number of a child’s medical practitioner.

- List of any allergies, illnesses or other medical conditions disclosed by the child’s parent or medical practitioner.

- Child’s immunization status

- Medication authorization from parents and any record of medication administered that are required by section 27 (Medications) of the Child Care Regulations

- Any authorization provided by the parent for excursions requiring or not requiring transportation.

- Any reports required by section 34 (injuries, unusual occurrences) of any injury or unusual or unexpected occurrences.

- Agreement for services entered into by the licensee and the child’s parent.

Health records can help early care and education programs identify preventative health measures, develop care plans for children with special needs, and determine whether or not a child should be excluded from care due to illness.

Staff Records

It is also important for records to be kept to document the health of all staff in an early care and education program. Staff records need to include the following information:

- Birthdate

- Resume

- Current job description

- Offer of employment or employment agreement (updated with any changes)

- Revenue Canada Taxation forms

- Performance reviews

- Record of in-service training

- Record of any disciplinary action

- Any correspondence regarding the employee

- Record of employment.

Documents that need to be in each staff’s file.

- Certificate of Qualification in ECE

- Certificates for first aid and CPR

- Criminal record check

- Copies of all medical reports for the employee

- Emergency medical information

Staff records must be:

- Only accessible to those who need to see it for supervision purposes.

- Stored in a locked cabinet or room in which the door can be locked

- Updated as changes occur.

The Importance of Keeping Staff Healthy

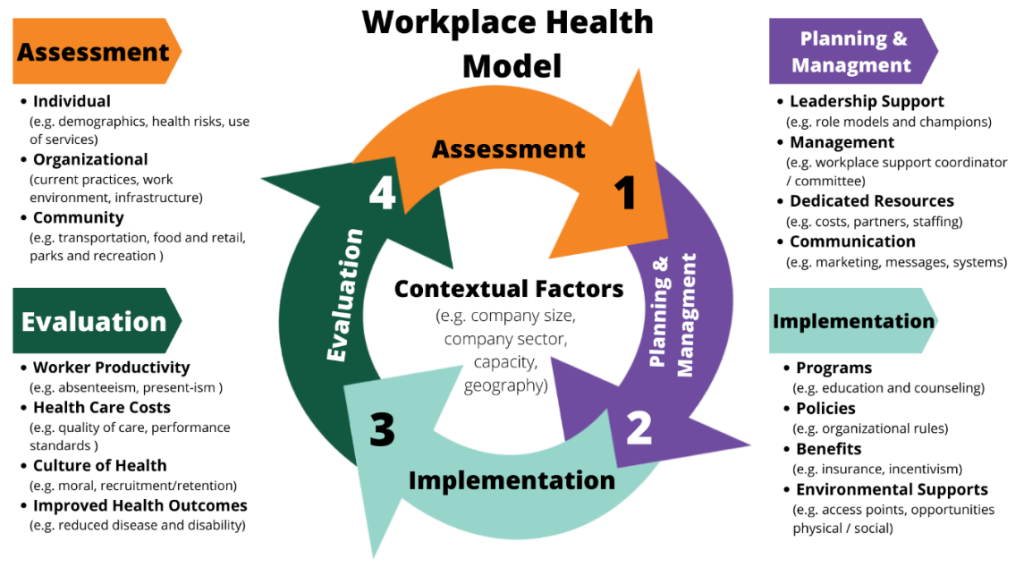

A culture of wellness is a working environment where an employee’s health and safety is valued, supported, and promoted through worksite, health and wellness programs, policies, benefits, and environmental supports. A culture of wellness for staff is going to be the foundation for creating a culture of health and safety for children.

Early childhood staff have health problems such as obesity and depression at rates above the national average. Early care and education salaries are often low, creating personal financial stress. Staff turnover rates are high. In general, early childhood educators are undervalued for the important and high-demand work they do.

Staff wellness and stability will affect the quality of services a program can deliver to families and children. Children need consistent, sensitive, caring, and stable relationships with adults. Adults who are well, physically and mentally, are more likely to engage in positive relationships. When we support staff well-being, we strengthen early care and education.

Programs can use the CDC’s Workplace Health Model to support the health of their staff.[5] It is outlined in this image (and a link is provided in the Further Resources to Explore feature at the end of the chapter).

Figure 7.3 – The CDC’s Workplace Health Model of assessment, planning and management, implementation, and evaluation.[6]

Occupation Health

Early Childhood education is a demanding occupation and it can take a toll on your body and mind. As students going into the field for the first time or those who are upgrading you need to remember that you cannot care for others unless you take care of yourself first.

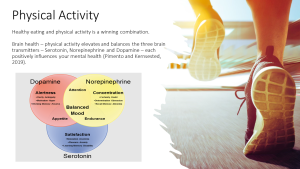

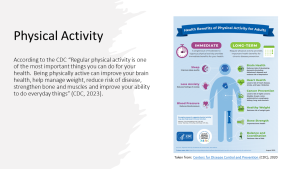

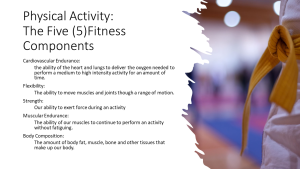

As caregivers, our focus is the care of others, both at our work and at home – as a result, many times we forget to care for ourselves. The PowerPoint slides below “Promoting Your Physical and Mental Health” highlights the importance of taking care of yourself.

Preventing Musculoskeletal Injuries

In the field of ECE, educators are constantly bending and twisting in different ways. These physical movements can add up and lead to Musculoskeletal injuries. The video below is from Safework NSW an Australian organization. The talking points they make regarding your responsibility and your employer’s responsibility are similar to what you would expect in Canada.

The video highlights some routine tasks that you will be doing in your work as an educator and provides ideas to avoid injuries in the workplace. Please disregard the instructions on how to lodge a complaint – that is specific to NSW. The rest will provide you with some ideas to think about to avoid common injuries among educators in child care centres.

Reducing the Risk of Injury to Child Care Workers

Outdoor Activities

Indoor Activities

Coat Room

Storage

Diaper Changing

Toileting

Nap/Rest time

Lifting and bending

Bonus: Stress and Noise

Watch the following video for more information about safe lifting techniques with children:

Video: Safe Lifting Techniques of Children by Pediatric Home Service [5:19]. Transcript available on YouTube.

Working with Art and Cleaning Products

Educators support children by maintaining a safe and healthy environment through the prevention and management of illnesses, ensuring safety checklists are regularly completed, conducting daily health checks, modelling appropriate nutritional practices, and implementing so many more measures. Educators are entitled to work in safe and healthy workplaces while they are nurturing the wellness and growth of young children.

Employers have the responsibility to provide safe working environments for employees. Employers are accountable to the Ministry of Labour and must provide health and safety training for all employees. Employees have the right to understand how to protect themselves and keep others safe in workspaces [7].

Watch the following video for information about WHMIS:

Psychological Well-being

It is worth noting that a strong foundation for educator wellness parallels that in which we strive to offer the children and families. This foundation includes appropriate sleep, nutrition and physical activity. As we work to create healthy spaces we have to enter our work days ready to handle big emotions and physically demanding work. This requires a level of understanding of our own emotional wellness and regulation. Taking care of the caregiver first allows us to be in a space where we can provide a healthy environment for children and families. This chapter will examine the many levels of wellness in the workplace, from digital wellness, and wellness strategies, to our obligations under law and regulation.

Almost 50% of Early Childhood Educators leave the field within the first 5 years of working. According to participants in a report, The Burnout Crisis: A Call to Invest in ECE and Child and Youth Workers, (2022) While many want to come into the field, many factors including the COVID pandemic have added to this crisis. A strong focus on educator wellbeing and mental health has become a priority while advocates work to fix the structural challenges of low pay and lack of pensions and benefits [8].

The following document was published prior to the Covid-19 pandemic but the research and reflective questions remain relevant to educators, currently working with children and families. Please read The Importance of Early Childhood Educator Mental Health & Well-Being: A guide to supporting educators and answer the reflective questions at the end. Journaling your responses will support your wellness as an early years practitioner (Ingriselli & Schempp, 2019).

Pause to Reflect

|

Now that we have an understanding of the importance of taking care of ourselves so that we can care for others, let’s look at how we can support children and their families to maintain good health.

Daily Health Checks

Every day an informal, observation-based quick health check should be performed on every child (before the parent/caregiver leaves).

“In a child care setting where lots of people are coming at the same time, it is hard to take a moment with each child. However, this welcoming routine can establish many things and is a good child development policy. This contact will help [teachers] better understand each child, help the children feel comfortable and good about themselves, reduce the spread of illness by excluding children with obvious signs of illness, and foster better communications with [families].”[9]

Early childhood educators should use their knowledge about what is normal for each child to identify any concerns about the child’s well-being, it is not an attempt to formally diagnose illness. The purpose of daily health checks is not to identify reasons for excluding children from the center. Instead, they are meant to address any concerns noticed during the health check, which may, in some cases, warrant considerations for excluding children to ensure their well-being and safety.

Conducting a Daily Health Check

Teachers should use all of their senses to check for signs of illness. This includes:

- Listening to what families tell you about how their child is feeling and what the child sounds like (hoarse voice, coughing, wheezing, etc.

- Looking at the child from head to toe (with a quick scan) to see if the child looks flushed, pale, has a rash, has a runny nose or mucus in the eyes

- Feeling the child’s cheek or neck (as part of a greeting) for warmth or clamminess

- Smelling the child for unusual smelling breath or a bowel movement.

Here are some signs to observe:

- The general mood and atypical behaviour

- Fever (elevated temperature)

- Rashes or unusual spots, itching, swelling, and bruising

- Complaints of not feeling well

- Symptoms of illness (coughing, sneezing, runny nose, eye or ear discharge, diarrhea, vomiting, etc.)

- Reported illness in child or family members[11][12]

Dental Hygiene

Dental hygiene is important to prevent Early Childhood Caries (ECC), which is a term used to describe tooth decay, including filled or extracted teeth due to decay, in the primary teeth (baby teeth). It is important to rethink the way we “treat” dental caries. Traditionally, we would wait until a child had a cavity and “treat” the cavity with a filling. In order to prevent ECC, we must intervene before the first cavity develops.[13] Early care and education programs can teach children and families about dental hygiene and oral care as well as implement good dental hygiene practices. Here are some ideas:

- Use teaching practices that engage children and promote thinking critically. Consider asking questions such as:

- How do you brush your teeth?

- Why do you brush your teeth?

- What else can you do to keep your mouth and teeth healthy?

- What happens if you don’t brush your teeth?

- Tell me about your last visit to the dentist.

- Integrate oral health into activities (in addition to tooth brushing). Some possibilities include:

- Have children separate pictures of foods that are good for oral health from pictures of foods that are high in sugar.

- Reading books with positive oral health messages to children.

- Having children pretend they are visiting a dental office.

- Singing songs about oral health

- Engage families in promoting oral health at home. Some ways to do this include:

- Working with families to find the best ways to position their child for tooth brushing. Remind families that young children cannot brush their teeth well until age 7 to 8. It is also important for a parent to brush their child’s teeth or help them with brushing.

- Asking families to take photographs of their child brushing his teeth and helping the child write stories about his experience.

- Helping families choose and prepare foods that promote good oral health.

- Encouraging families to ask their children what they learned about oral health in the centre that day.

- Offering families suggestions for at-home activities that support what children are learning about oral health at the centre.[14]

A Suggestion for Brushing Teeth as a Group

- Sitting at a table in a circle, children brush their teeth as a group activity every day.

- Give each child a small paper cup, a paper towel, and a soft-bristled, child-sized toothbrush.

- Put a small (pea-sized) dab of fluoride toothpaste on the inside rim of each cup, and have children use their toothbrushes to pick up the dabs of toothpaste.

- Brush together for two minutes, using an egg timer or a song that lasts for about two minutes.

- Brush your teeth with the children to set an example, and remind them to brush all of their teeth, on all sides.

- When the two minutes are up, have the children spit any extra toothpaste into their cups, wipe their mouths and throw the cups and paper towels away.

- Children can go to the sink in groups to rinse their toothbrushes and put the toothbrushes in holders to dry.[15]

Sleep Hygiene

It’s important to get enough sleep. Sleep supports mind and body health. Getting enough sleep isn’t only about total hours of sleep. It’s also important to get good quality sleep on a regular schedule to feel rested upon waking.

Sleep is an important part of life! Young children spend around half of their time asleep.[17]

- Babies need to sleep between 12 and 16 hours a day (including naps).

- Toddlers need to sleep between 11 and 14 hours a day (including naps).

- Preschoolers need to sleep between 10 and 13 hours a day (including naps).

- School-aged children need 9 to 12 hours of sleep each night.[18]

We know how busy they are when they are awake, but what are they doing during all of those restful hours? Actually, sleep has many purposes.

- Growth: Growth hormone is released when children sleep (Berk 2002, 302). Young children are growing in their sleep, and since they have a lot of growing to do, they need all the sleep they can get.

- Restoration: Some sleep researchers have found that sleep is important for letting the brain relax and restore some of the hormones and nutrients it needs (Jenni & O’Conner 1995, 205).

- Memory: Sleep is also a time when the brain is figuring out what experiences from the day are important to remember (Jenni & O’Conner 1995, 205).

- Health: One study found that infants and toddlers need at least 12 hours of sleep in a 24 hour day. When infants and toddlers had less than 12 hours they were more likely to be obese by the age of 3 (Taveras et. al. 2008, 305).[19]

For more information on healthy sleep habits, read the following article: Healthy Sleep Habits for Young Children

The Culture of Sleep and Child Care

Across the world, people sleep in different ways. Some people sleep inside, some sleep outside. Some people sleep in beds, others in hammocks or on mats on the floor. Some people sleep alone, some sleep with a spouse or children or both. Some people sleep only at night, while others value a nap during the day. How, when, and where people choose to sleep has a lot to do with their culture, traditions, and customs. This can include where they live, how their family sleeps, and even how many bedrooms are in their home. Teachers have a role in providing a sleep environment that is comfortable and safe for the children in their care while honouring families’ cultural beliefs.

What can teachers do to help young children feel more “at home” when it is time for them to rest?

- Think of sleep and sleep routines as part of the child’s individualized curriculum.

- Classroom teachers should meet with a family before a child enters their care. This is an opportunity to find out about a child’s sleep habits before they join the classroom. When you know how a baby sleeps at home, you can use that information to plan for how they might sleep best in your care.

- Brainstorm ways to adapt your classroom to help a child feel “at home” during rest times. For example, a baby who is used to sleeping in a busy environment might nap better if you roll a crib into the classroom. Some mobile infants and toddlers might have a hard time sleeping in childcare because they think they will miss something fun! These children benefit from having a very quiet place to fall asleep. When you have a positive relationship with a baby it will be easier to know what will help them relax into sleep.

- Encourage families to bring in “a little bit of home” to the program – like a stuffed animal or special blanket. A comfort item from home can help children feel connected to their families. They might want that comfort all day. The comfort item from home can also help children make the transition to sleep while in your care. Make sure that infants under one year of age do not have any extra toys or blankets in the crib with them.

- Share with families what you learn about their child. Use pick-up and drop-off times to ask questions about sleep at home. Families can share information that could make their child more comfortable in your care. You can be a resource for families about sleep and their child. Remember that families are the experts on their child.

Napping and Individual Differences

Have you noticed that some children will fall asleep every day at the same time no matter what else is going on? These kids could fall asleep on their lunch if it is served too late! Have you known children who seem to fall asleep easily some days and other times just can’t settle into sleep? These children might need a very stable routine. Some toddlers nap less and sleep more at night while others need to have a long sleep during the day.

Temperament and Sleep

Some of the different patterns in children’s sleep have to do with their temperament (Jenni & O’Connor 2005, 204). Temperament is like the personality we are born with. Some children are naturally easy-going and adapt to new situations while others really need a routine that is the same every day. One child might fall asleep easily just by putting her in her crib or cot when she is drifting off to sleep. Another child might fall asleep in your arms but startle awake the moment he realizes he has been laid down alone.

Circadian Rhythms and Sleep

Something else that can make nap time easy or difficult for young children has to do with their natural sleep cycles. Everyone has a kind of “clock” inside of their bodies that tells them when they are hungry or sleepy. The cycle of this clock is called circadian rhythms. Circadian rhythms are the patterns of sleeping, waking, eating, body temperature and even hormone releases in your body over a twenty-four-hour period. How much children need to sleep, when they feel tired, and how easily they can fall asleep are all related to their circadian rhythms (Ferber 2006, 31).

Meeting Each Individual Child’s Sleep Needs

Thinking about the circadian rhythms and temperament reminds us how each child is different. That is why it is important to have nap times that meet the needs of all children in your care. Helping young children learn to recognize their bodies’ needs and find ways to meet those needs is a very important skill of self-regulation.[20]

Individualizing Nap Schedules

|

|

Creating a space for sleepy children can allow them to relax or nap when their body tells them they are tired. It can take some creativity to figure out how to let a young child nap or rest when they are tired.

What do you do if a child won’t nap when others are? How does one child rest quietly in a busy classroom? Two-and-a-half-year-old Henry is new to your classroom. His mother has shared with you that he does not nap during the day with her. When nap time comes around you can tell that Henry does not seem very tired. What can you do for Henry, or other children like him, while the rest of the class sleeps? · Do you have a “cozy corner” that could also be a one-child nap area? · Are there soft places to sit and relax with a book or stuffed animal? · Are books or other quiet activities provided if a child isn’t able to rest or settle when other children are? · Are children provided techniques and strategies for calming their bodies e.g. deep breathing, tensing and relaxing their bodies, feeling their heartbeat, etc?[22] |

Developmental and Health Observations

There are specific health conditions that impact learning and development, which can be identified and treated early. These conditions can be identified through early health screening.[23]

Screening is the first step in getting to know a child new to the early learning centre. This “baseline data” helps staff plan and individualize services. It also helps them identify “red flags” for further examination or evaluation. When concerns go unidentified, they can lead to more significant problems.[24]

Observation helps staff and families:

- Celebrate milestones: Every family looks forward to seeing a child’s first smile, first step, and first words. Regular screenings with early childhood professionals help raise awareness of a child’s development, making it easier to celebrate developmental milestones.

- Promote universal screening: All children need support in the early years to stay healthy and happy. Just like regular hearing and vision screenings can ensure that children are able to hear and see clearly, developmental and behavioural screenings can ensure that children are making progress in areas such as language, social, or motor development.

- Identify possible delays and concerns early: With regular screenings, families, teachers, and other professionals can ensure that young children get the services and support they need as early as possible to help them thrive.

- Enhance developmental supports: Families are children’s first and most important teachers. Tools, guidance, and tips recommended by experts, can help families support their children’s development.[25]

Observation and screening are part of a larger process, professionals use to learn about children’s health and development. In partnership with families, developmental observation (screening), and assessment keep children on track developmentally.

What is the Difference Between Observation/screening , Assessment, and Evaluation

| Observation (Screening)

The observation process is the preliminary step to determine if sensory, behavioural, and development skills are progressing as expected. The observation or screening itself does not determine a diagnosis or need for early intervention. Assessment Assessment is an ongoing process to determine a child’s and family’s strengths and needs. The assessment process should be continued throughout a child’s eligibility and be used to determine strategies to support the development of the child in the classroom and at home. Evaluation by a qualified professional A formal evaluation is performed by a qualified professional to identify or diagnose a developmental, sensory, or behavioural condition or disability requiring intervention. Only children who were identified through screening and ongoing assessment as possibly having a condition or disability might require intervention. |

A couple of important things to remember about observation and screening:

- Children develop rapidly during the first three years of life, so keeping a watchful eye on the health and development of infants and toddlers is critical.

- Most early childhood programs serve diverse families. Therefore, the best screening tools gather information in ways that respond to culture and language.[26]

Developmental Monitoring

The first years of life are very important for a child’s development. Early experiences make a difference in how young children’s brains develop and can influence lifelong learning and health. Early childhood educators spend a great deal of time with young children and are instrumental in determining many of the kinds of experiences they will have. Developmental monitoring means observing and noting specific ways a child plays, learns, speaks, acts, and moves every day, in an ongoing way. Developmental monitoring often involves tracking a child’s development using a checklist of developmental milestones.

Teachers are in a unique position to monitor the development of each child in their care. They may be the first ones to observe potential delays in a child’s development. Working with groups of same-aged children can help teachers recognize children who reach milestones early and late. Working with children of different ages can help teachers notice if a child’s skills are more similar to those of a younger or older child than to those of his or her same-aged peers. Because teachers spend their day teaching, playing with, and watching children, they may find themselves concerned that a child in their care is not reaching milestones that other children his or her age have, or they may have families ask them if they are concerned about their child’s development.[27]

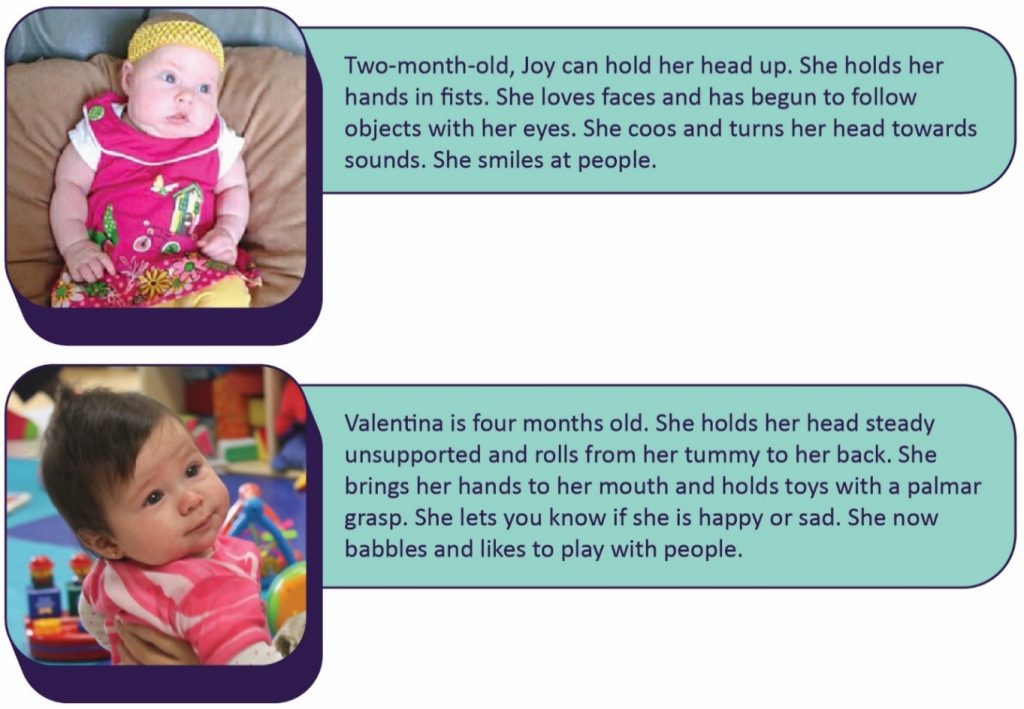

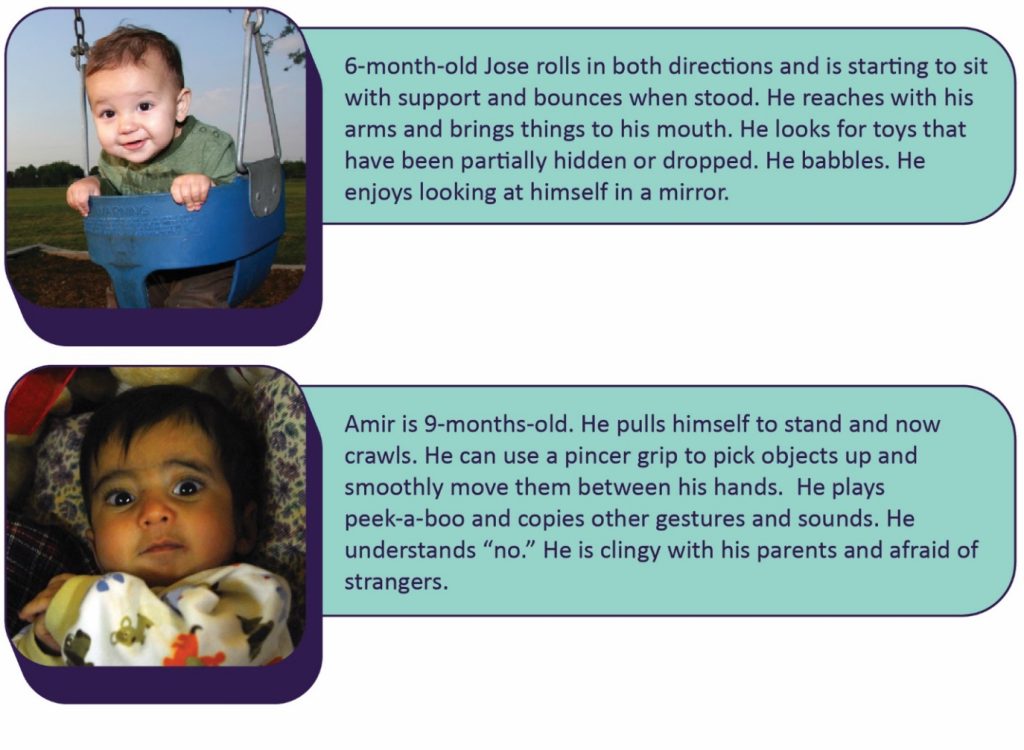

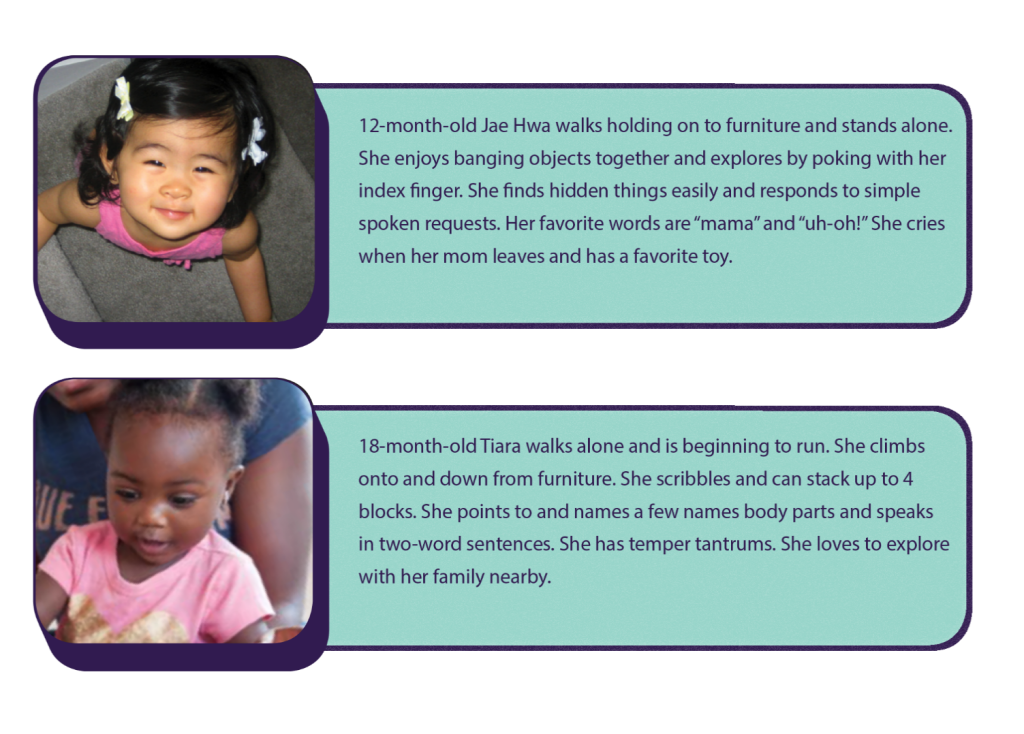

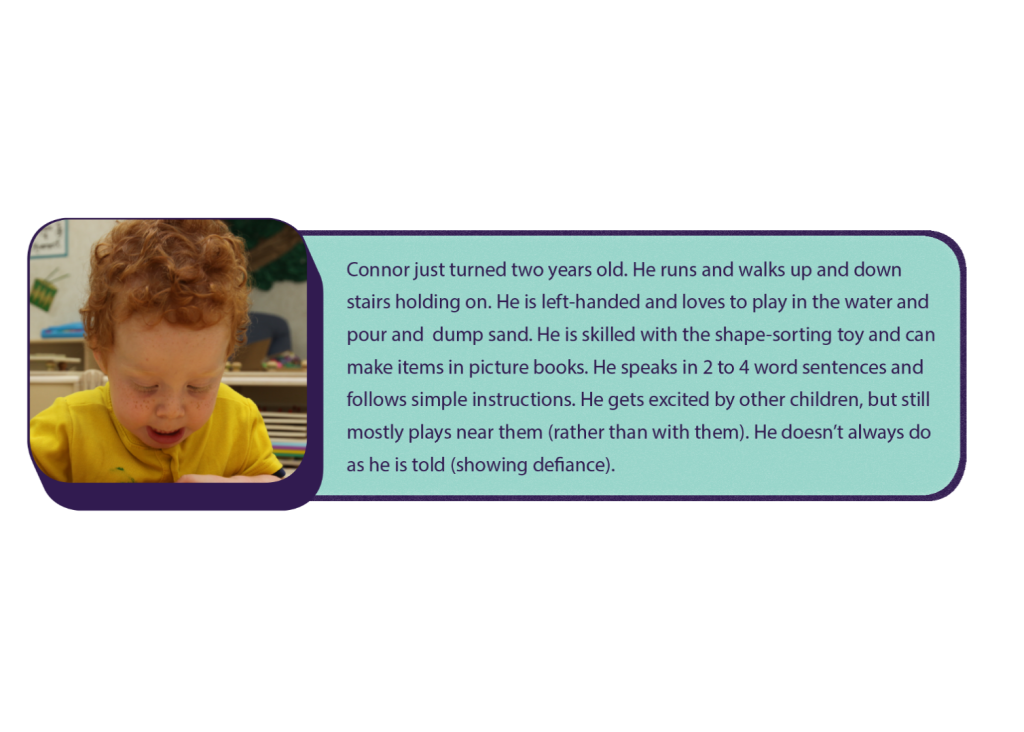

A complete list of developmental milestones for children from birth to age 8 is in Appendix I, but here are some examples of children from birth to age 5 that showcase typical milestones for their age.

Development Monitoring

The first time I heard the term “developmental monitoring,” I was really intimidated and thought, “this sounds really complicated and time-consuming. How am I going to do that on top of everything else I have to do during the day?”

I was so relieved when I found out that “developmental monitoring” is just a fancy way of saying “watch, observe and record what the kids are doing to make sure they’re on track.” I just mark on a simple checklist when children meet milestones.

We observe children every day anyway. We watch what they’re doing when they play in the classroom or outside, when they eat, and so on. Monitoring is just that: watching and observing, and recording what you see. Making a check on a list when a child meets a milestone takes about two seconds, and it’s easier than just about anything else we do all day. It’s definitely easier than getting a room full of toddlers to sleep at naptime, and it’s a lot more fun than changing diapers!

And if that’s all it takes to really make sure each child is on track and to make sure I’m not missing anything in all the hubbub each day, I’m all over it!

-Ms. Carolyn (an early childhood educator)[28]

Pause to Reflect

| Do you feel like you are less knowledgeable about or have less experience with a specific age of children (refer to Appendix I to see detailed milestones from 2 months through 12 years of age)? What can you do to improve your familiarity with the milestones for children that age? Why would this be important? |

Screening

Developmental screening is a more formal process that uses a validated screening tool at specific ages to determine if a child’s development is on track or whether he or she needs to be referred for further evaluation.[30]

Screening alone is not enough to identify a developmental concern. Rather, it helps staff and families decide whether to refer a child for more evaluation by a qualified professional. The earlier a possible delay is identified, the earlier a program can refer a child for further evaluation and additional support and services.[31]

Most children with developmental delays are not identified early enough for them to benefit from early intervention services; early care and education programs can help change that. Although about 1 in 6 children has a developmental disability, less than half of these children are identified as having a problem before starting school.

Too often, adults don’t recognize the signs of a potential developmental disability, they are not sure if their concern is warranted, or they don’t have resources to help make their concern easier to talk about. But pinpointing concerns and talking about them is very important to get a child the help he or she might need.[32]

Vision Screening

Families and early care and education staff cannot always tell when a child has trouble seeing. Observation alone isn’t enough. This is why implementing evidence-based vision screening throughout early childhood is important.

Timely vision screening is an important step toward early detection of any possible vision problems. Early detection can lead to an effective intervention and help to restore proper vision. Young children rarely complain when they can’t see well because, to them, it’s normal.

It is easier for families to partner with early care and education staff and health care providers when they understand how vision influences their child’s development and learning. Preparing families about what to expect from a vision screening helps them know how to prepare their child. It is also important to talk about who will have access to their child’s screening results. One of the best ways to promote children’s vision health is by developing and implementing policies and procedures that both define and support ways for staff to collaborate with families.

Include questions on the program’s family health history form to identify children who may have a higher risk of vision problems. For example is there a family history of amblyopia, strabismus, or early and serious eye disease?

Provide resources to help families learn more about healthy eyes and the importance of early detection of vision problems. Do families know that it isn’t always possible to tell if children have a vision problem just by looking at their eyes? Or that young children seldom complain when they can’t see well?

In addition to assuring timely vision screening, programs can support children and families who have been given treatment recommendations from an eye specialist (such as wearing glasses or patching one eye for amblyopia), as well as reminding families of follow-up visits to the eye doctor whenever recommended.

It is important to remember that screening only provides a vision assessment at one moment in time. Occasionally a family member or teacher will identify a new or different vision concern after a child has been previously screened. In addition, as children grow their eyes change and new signs of an eye problem or blurred vision can arise as they mature. Programs should address this new concern with the parent and the health care provider promptly.[34]

Common indicators for vision issues.[35]

Many vision problems that are found early can be treated. Call your pediatrician or family doctor if you notice that your child’s eyes:

- are often red

- look different than usual

- make tears more than usual

- don’t line up or move together

- look crossed (after 6 months of age)

- have pupils (centers) that are different sizes, or if the pupils or iris are an unusual colour, or have changed colour

- complains of eye discomfort

- rubs their eyes a lot

- seems very sensitive to light

- has trouble focusing on or following an object

- not being able to see objects at a distance

- squinting

- trouble with reading

- sitting too close to the TV or other screen

- headaches

Hearing Screening

Families and early care and education staff cannot always tell when a child is deaf or hard of hearing. Observation alone isn’t enough. This is why implementing evidence-based hearing screening throughout early childhood is important.

Hearing helps us communicate with others and understand the world around us. However, 3 of every 1,000 children in Canada are born severely deaf and another 3 in 1000 babies have serious hearing loss. [50]. A child may also experience a decline in hearing ability at any time caused by illness, physical trauma, or environmental or genetic factors. It is estimated that the incidence of permanent hearing loss doubles by the time children enter school. A child may have difficulty hearing in one ear or both ears. The difficulty may be temporary or permanent. It may be mild or it may be a complete inability to hear spoken language and other important sounds.

Any inability to hear clearly can get in the way of a child’s speech, language, social and emotional development, and school readiness. Intervention may improve social and emotional and academic achievement when children who are deaf or hard of hearing are identified early.

Common indicators for hearing issues

Encourage parents to seek out medical advice from their doctor if their infant or toddler child:

- was not screened as a newborn and ask for a hearing test.

- stops babbling (usually parents don’t notice this until after 12 months of age).

- does not pay attention or react to loud noises around the house (such as a doorbell, telephone, dog barking).

- does not turn toward sound by 3-4 months of age or turn toward spoken words by 9 months of age.

- has had frequent ear infections and/or fluid draining from the ears.

- does not say single words by 12 months of age.

- does not understand simple phrases unless the person talking is facing them (such as, “Go get your shoes.”).

- starts speaking later than usual. Read our guide on child development from birth to age 4.

- speaks loudly.

See your doctor if your pre-school or school-age child:

- starts speaking later than usual, or is difficult to understand.

- needs things to be repeated.

- speaks loudly or turns up the volume on electronics so much that it disturbs others.

- has difficulty following simple instructions such as “Go brush your teeth and then wash your face.”

- seems like they are not paying attention, especially when in a group or noisy setting, like child care or school.

- has trouble learning in school (vision should also be checked).

- is easily frustrated, more so than other children of the same age.

Remember, the signs of hearing loss can be difficult to detect and may get worse after birth. You may only notice them when the hearing loss has been present for many months, or even years. Young children are very good at making up for any difficulties they are having, even if they hear very little.

An evidence-based hearing screening is a way to identify children who need an evaluation to determine if they are deaf or hard of hearing. Prior to discharge from the hospital, almost all newborns are screened and an evaluation is necessary for those who do not pass the screening.

It is easier for families to partner with early care and education staff and health care providers when they understand how hearing influences their child’s speech and language development, socialization, and learning. Preparing families about what to expect from a hearing screening helps them know how to prepare their child. It is also important to talk about who will have access to their child’s screening results. When a child does not pass a hearing screening, programs can provide support to help families follow up with referrals and any recommended treatment. If a child is identified as deaf or hard of hearing, a collaboration between the family, the early care and education program, and the child’s audiologist and other early intervention providers, such as speech and language pathologies, will be helpful. Share information with the family about the importance of hearing for children’s language development and communication. This supports a family’s health literacy, and it may help them complete the follow-up steps.

Pause to Reflect

| Do you remember getting your vision or hearing screened during your childhood? If you were diagnosed with vision or hearing impairments, how was it discovered? At what age did that happen? |

Lead Screening

Lead screening measures the level of lead in the blood. Lead is a poison that is very dangerous for young children because of their small size and rapid growth and development. It can cause anemia, learning difficulties, and other medical problems.

Children can inhale or swallow lead through exposure to:

- Home or child care environments, including those:

- Built before 1960 with peeling paint or renovation

- Located near a highway or lead industry

- Family members who work with lead or have been treated for lead poisoning

- Imported ceramic pottery for cooking, storing, or serving food

- Home remedies with lead

- Certain candies may contain high levels of lead in the wrapper or stick. Be cautious when providing imported candies to children.

- Eating paint chips or dirt

- Water pumped through lead-based pipes

Lead screening involves a blood lead test, from a finger stick or a venous blood draw. It is recommended at 12 months and 24 months of age. Children from 3 to 6 years of age should have their blood tested if they have not been tested

Symptoms of Lead Poisoning

Most children with lead poisoning show no symptoms. However, you might notice:

- Developmental delay

- Learning Difficulties

- Irritability

- Headaches

- Poor appetite or stomachache

- Weight loss

- Fatigue and sluggishness

- Slow growth and development

- Vomiting

- Constipation

- Hearing loss

New recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) state that if screening indicates a lead level of five micrograms per deciliter or more, the child should be referred to a health professional.[37]

Lead has negative outcomes on a variety of things, including:

- Attention (easily distracted, challenges with sustained attention, hyperactivity)

- executive functions (problems with planning, impulse control, flexible thinking, etc.)

- visual-spatial skills (problems related to visual perception, memory, organization, and reasoning with visually presented information)

- social behaviour (aggression, disruptive behaviour, poor self-regulation)

- speech and language (problems with phonological and sentence processing and spoken word recognition)

- fine and gross motor skills (unsteadiness, clumsiness, and problems with coordination, visual-motor control, and dexterity)[38]

Depending on the effects of lead poisoning, early care and education programs can implement intervention services to support the child. Other treatments include:

- Nutrition counseling

- Iron supplements

- Medication to remove the lead from the blood (Chelation therapy)

- Follow-up testing of the child’s blood

- Referral for developmental testing[39]

Social, Emotional and Behavioral Screening

Young children are learning to get along with others and manage their own emotions. When a child enters a program, staff get to know what social and emotional skills children are working on.

Social and emotional health—the ability to form strong relationships, solve problems, and express and manage emotions—is critical for school readiness and lifelong success. Without it, young children are more likely to:

- Have difficulty experiencing or showing emotions, which may lead to withdrawal from social activities and maintaining distance from others

- Have trouble making friends and getting along with others

- Have behaviours, such as biting, hitting, using unkind words, or bullying—behaviours that often lead to difficulty with learning, suspension or expulsion, and later school dropout[41]

More information about this topic can be found in other parts of this book. Behavior has been addressed in Chapter 3 in the section on Interpersonal Safety and children’s mental health is the focus of Chapter 11.

Screening Resources in Saskatchewan

![]() “Saskatchewan Early Childhood Intervention Program (ECIP) services are offered in 14 regions across the province and is funded by the Ministry of Education. They provide specialized services to families of young children between birth and school-age, who are at risk for, have a diagnosis of or exhibit developmental delays. Click on the logo to view their website.

“Saskatchewan Early Childhood Intervention Program (ECIP) services are offered in 14 regions across the province and is funded by the Ministry of Education. They provide specialized services to families of young children between birth and school-age, who are at risk for, have a diagnosis of or exhibit developmental delays. Click on the logo to view their website.

The video below will introduce you to what ECIPs is about

A wonderful resource is the Moms & Kids Programs and Services.

“Moms and Kids Health Saskatchewan is a program within the Saskatchewan Health Authority that is specifically designed to support patients who are pregnant or having babies, for children and for their families” Click on the logo to view their website

Child Development and Rehabilitative Programs they offer include:

- Hearing Health

- Home Care

- Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Physical Therapy

- Psychology

- Speech and Language Pathology

Check out their website: https://momsandkidssask.saskhealthauthority.ca/about-us/moms-kids-programs-and-services

Summary

By keeping accurate records, conducting daily health checks, supporting children’s development of good dental hygiene, and by providing for individual children’s sleep needs early care and education programs can help promote good health on a daily basis. When programs monitor and screen children, they can ensure that conditions or situations that might interfere with a child’s health or well-being can be identified and supports put in place to mitigate potential negative effects.

Chapter 7 Review

[h2p id=”12″]

Resources for Further Exploration

· Head Start’s Health Literacy: Tips for Health Managers: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/publication/health-literacy-tips-health-managers

· The Culture of Sleep and Child Care: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/nycu-culture-of-sleep-pdf.pdf

· The Foundations of Lifelong Health Are Built in Early Childhood https://46y5eh11fhgw3ve3ytpwxt9r-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/Foundations-of-Lifelong-Health.pdf

· Birth to 5: Watch Me Thrive! An Early Care and Education Provider’s Guide for Developmental and Behavioral Screening https://www2.ed.gov/about/inits/list/watch-me-thrive/files/ece-providers-guide-march2014.pdf

· Prevent Blindness: 18 Vision Development Milestones From Birth to Baby’s First Birthday https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/no-search/18-key-vision-questions-to-ask-in-year-1.pdf

· CDC’s Hearing Loss in Children https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/index.html

· Early Childhood Hearing Outreach http://www.infanthearing.org/earlychildhood/

· Developmental Screening and Assessment Instruments with an Emphasis on Social and Emotional Development for Young Children Ages Birth through Five https://ectacenter.org/~pdfs/pubs/screening.pdf

· Links to Commonly Used Screening Instruments and Tools https://toolkits.solutions.aap.org/selfserve/ssPage.aspx?SelfServeContentId=screening_tools

· Educational Interventions for Children Affected by Lead https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/publications/educational_interventions_children_affected_by_lead.pdf

· Watch Me! Celebrating Milestones and Sharing Concerns course from CDC https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/watchmetraining/docs/watch-me-training-2019-508.pdf

· CDC’s Developmental Milestones http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/pdf/checklists/all_checklists.pdf

· CDC’s “Learn the Signs. Act Early.”: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/freematerials.html

References

- Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion: An International Conference on Health Promotion, Government of Canada (2017) retrieved on Nov. 27, 2023. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/ottawa-charter-health-promotion-international-conference-on-health-promotion.html ↵

- Mental Health Promotion; Promoting Mental Health Means Promoting the Best of Ourselves by Public Health Agency of Canada, is licensed under Open Government Licence - Canada. ↵

- Image by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- Image is in the public domain ↵

- Promoting Organizational and Staff Wellness by Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center is in the public domain ↵

- Image info by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain, Image by COC OER team is licensed under CC-By-4.0. ↵

- From "Holistic Care and Wellness in Early Years Setting" by Barbara Jackson &Sheryl Third, Copyright 2023, Used with permission by Fanshawe College and Open Library ↵

- From "Holistic Care and Wellness in Early Years Setting" by Barbara Jackson & Sheryl Third, Copyright 2023, Used with permission by Fanshawe College and Open Library ↵

- California Child Care Health Program. (2011). Health and Safety in the Child Care Setting: Prevention of Infectious Disease. University of California San Francisco. Retrieved from https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/idc2book.pdf ↵

- Image by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵

- California Child Care Health Program. (2011). Health and Safety in the Child Care Setting: Prevention of Infectious Disease. University of California San Francisco. Retrieved from https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/idc2book.pdf ↵

- Daily Health Check by County of Los Angeles Public Health is in the public domain ↵

- Oral Health for Head Start Children: Best Practices by IHS Head Start is in the public domain ↵

- Brush Up on Oral Health June 2017 by Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center is in the public domain ↵

- Classroom Circle Brushing Quick Reference by IHS Head Start is in the public domain ↵

- Image from Steps for Toothbrushing at the Table: Growing Healthy Smiles in Early Care and Education Programs by Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center is in the public domain ↵

- The Culture of Sleep and Child Care by Early Head Start National Resource Center is in the public domain ↵

- Get Enough Sleep by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is in the public domain ↵

- The Culture of Sleep and Child Care by Early Head Start National Resource Center is in the public domain ↵

- The Culture of Sleep and Child Care by Early Head Start National Resource Center is in the public domain ↵

- Image by jitpawee_s on Pixabay. ↵

- The Culture of Sleep and Child Care by Early Head Start National Resource Center is in the public domain ↵

- Healthy Children Are Ready to Learn by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain ↵

- Health Services Newsletter (October 2013) by the Office of Head Start National Center on Health is in the public domain ↵

- Birth to 5: Watch Me Thrive! by the U.S. Department of Education is in the public domain ↵

- Screening: The First Step in Getting to Know a Child by Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center is in the public domain ↵

- Watch Me! Celebrating Milestones and Sharing Concerns by the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities is in the public domain ↵

- Watch Me! Celebrating Milestones and Sharing Concerns by the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities is in the public domain ↵

- Images by Ian Joslin and Anthony Flores are licensed by CC-BY 4.0 ↵

- Watch Me! Celebrating Milestones and Sharing Concerns by the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities is in the public domain ↵

- Developmental Screening for Children Ages Birth to 5 by Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center is in the public domain ↵

- Watch Me! Celebrating Milestones and Sharing Concerns by the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities is in the public domain ↵

- Image by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain ↵

- Vision Screening Fact Sheet by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain ↵

- Nemours KidsHealth (2023). Retrieved from https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/vision.html ↵

- Hearing Screening Fact Sheet by the National Center on Early Childhood and Wellness is in the public domain ↵

- Lead Screening: Well-Child Health Care Fact Sheet by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain ↵

- Educational Interventions for Children Affected by Lead by the National Center for Environmental Health is in the public domain ↵

- Saskatchewan Health Authority (2023). retrieved from https://www.saskhealthauthority.ca/your-health/conditions-diseases-services/healthline-online/hw119898#:~:text=Whether%20your%20child%20needs%20to,that%20involves%20working%20with%20lead. ↵

- Image by Christine Szeto is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- About Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation (IECMHC) by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration is in the public domain ↵