Chapter 9: Supportive Health Care

Read Time: 31 mins

Illness in Early Care and Education Programs

Identifying Infectious Disease

Common Cold

Influenza (Flu)

Sinusitis (Sinus Infection)

What to Do When a Child Requires Exclusion

Caring for Mildly Ill Children

References

Chapter 9: Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Identify symptoms of infectious disease that are common during early childhood.

- Outline criteria for exclusion from care for ill children and staff.

- Describe considerations programs must make regarding caring for children who are mildly ill.

- Recall licensing requirements for handling medication in early care and education programs.

- Explain the communication about illness that should happen between families and early care and education programs.

Illness in Early Care and Education Programs

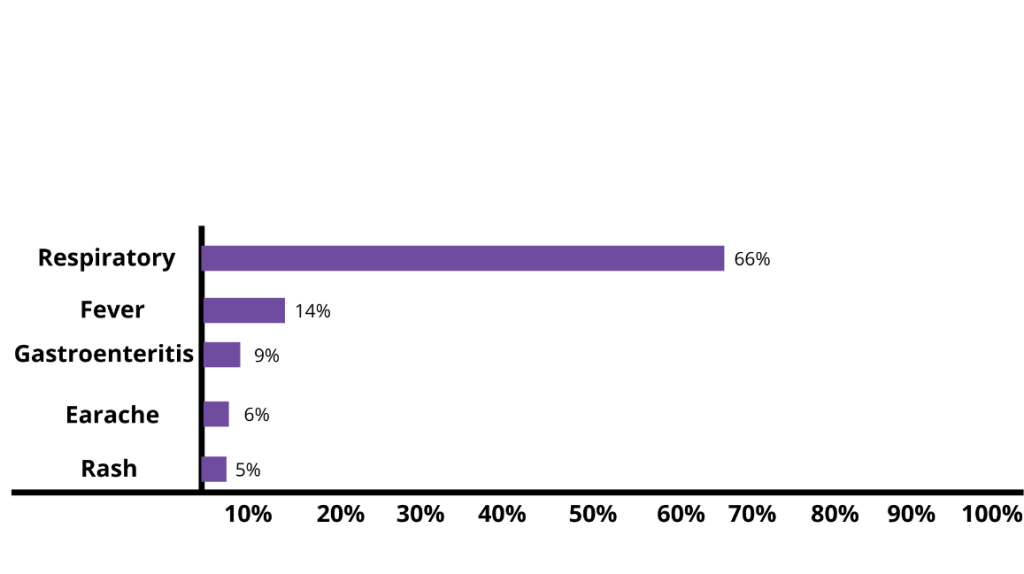

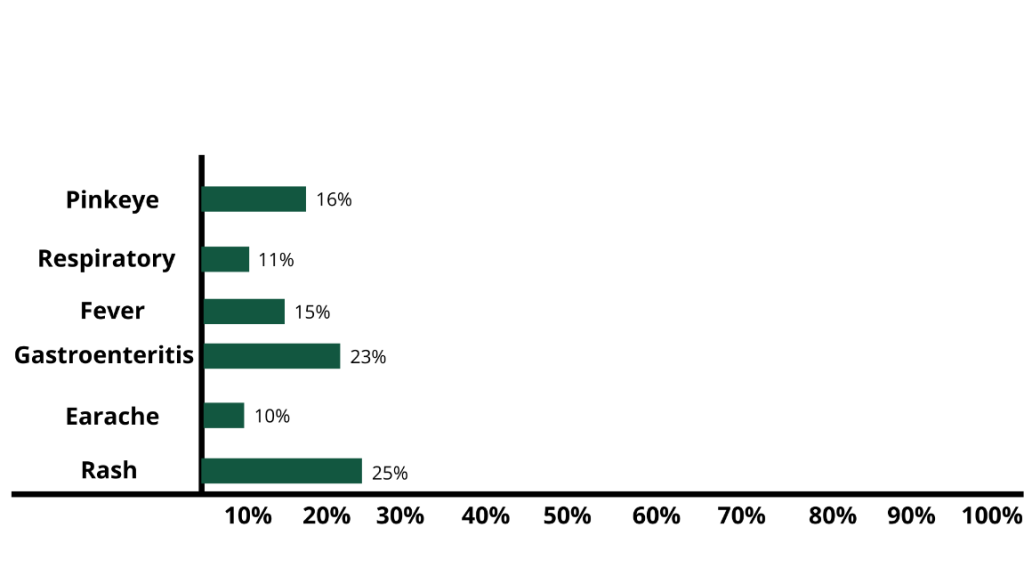

The most frequent infectious disease symptoms that are reported by early care and education settings are sore throat, runny nose, shortness of breath or cough, fever, vomiting and diarrhea (gastroenteritis), earaches, and rashes.

However, these are not the symptoms that necessarily lead to absences. Although respiratory symptoms are most common, it’s rashes and gastrointestinal diseases that more often keep children from attending their early education programs. This reflects exclusion policies more than the real risk of serious illness.[2]

It’s important for early childhood programs to identify illness accurately and respond in ways that protect all children and staff’s health (whether it be to allow them to stay in care or to exclude them from care).

Identifying Infectious Disease

When you are familiar with different infectious diseases, it’s easier to identify them in children and know whether or not children (and staff) who are affected should be excluded from the early care and education program.

Common Cold

A child is sneezing and has a stuffy, runny nose. It’s quite likely that they have a common cold. As presented in Chapter 8, children get sick many times a year, probably between 4 and 12 times, depending on age and amount of time in child care. Many of these are likely due to the common cold. More than 200 viruses can cause a cold, but rhinoviruses are the most common type.

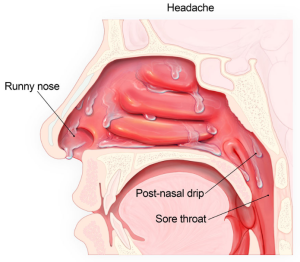

Symptoms of a cold usually peak within 2 to 3 days and can include:

- Sneezing

- Stuffy nose

- Runny nose

- Sore throat

- Coughing

- Mucus dripping down your throat (post-nasal drip)

- Watery eyes

- Fever (although most people with colds do not have fever)

When viruses that cause colds first infect the nose and air-filled pockets in the face (sinuses), the nose makes clear mucus. This helps wash the viruses from the nose and sinuses. After 2 or 3 days, mucus may change to a white, yellow, or green colour. This is normal and does not mean an antibiotic is needed. Some symptoms, particularly runny nose, stuffy nose, and cough, can last up to 10 to 14 days, but those symptoms should be improving during that time.

There is no cure for a cold. It will get better on its own—without antibiotics. When a child with a cold is feeling well enough to participate and staff are able to provide adequate care for them and all of the other children, the child does not need to be excluded from care.

Because colds can have similar symptoms to flu, it can be difficult to tell the difference between the two illnesses based on symptoms alone. Flu and the common cold are both respiratory illnesses, but they are caused by different viruses.[5]

Influenza (Flu)

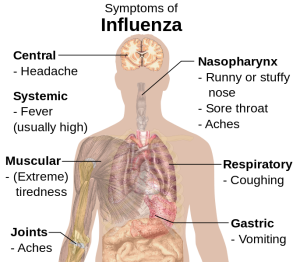

In general, flu is worse than a cold, and symptoms are more intense. People with colds are more likely to have a runny or stuffy nose. Colds generally do not result in serious health problems, such as pneumonia, bacterial infections, or hospitalizations. Flu can have very serious associated complications.[6]

Flu can cause mild to severe illness, and at times can lead to death. Flu usually comes on suddenly. People who have flu often feel some or all of these symptoms:

- Fever (common, but not always) or feeling feverish/chills

- cough

- sore throat

- runny or stuffy nose

- muscle or body aches

- headaches

- fatigue (tiredness)

- some people may have vomiting and diarrhea, though this is more common in children than adults.

Most people who get the flu will recover in a few days to less than two weeks, but some people will develop complications (such as pneumonia) as a result of the flu, some of which can be life-threatening and result in death.

Sinus and ear infections are examples of moderate complications from the flu, while pneumonia is a serious flu complication that can result from either influenza virus infection alone or from co-infection of the flu virus and bacteria. Other possible serious complications triggered by flu can include inflammation of the heart (myocarditis), brain (encephalitis) muscle (myositis, rhabdomyolysis) tissues, and multi-organ failure (for example, respiratory and kidney failure). Flu virus infection of the respiratory tract can trigger an extreme inflammatory response in the body and can lead to sepsis, the body’s life-threatening response to infection. Flu can also make chronic medical problems worse. For example, people with asthma may experience asthma attacks while they have flu.[8]

A yearly flu vaccine is the first and most important step in protecting against influenza and its potentially serious complications for everyone 6 months and older. While there are many different flu viruses, flu vaccines protect against the 3 or 4 viruses that research suggests will be most common. Flu vaccination can reduce flu illnesses, doctor’s visits, missed school due to flu, prevent flu-related hospitalizations, and reduce the risk of dying from influenza. Also, there are data to suggest that even if someone gets sick after vaccination, their illness may be milder.[9]

Once a person has the flu, their healthcare provider may recommend antiviral drugs. When used for treatment, antiviral drugs can lessen symptoms and shorten the length of sickness by 1 or 2 days. They also can prevent serious flu complications, like pneumonia. For people at high risk of serious flu complications (including children), treatment with antiviral drugs can mean the difference between milder or more serious illness possibly resulting in a hospital stay. CDC recommends prompt treatment for people who have influenza infection or suspected influenza infection and who are at high risk of serious flu complications.[10]

As with a cold, a child with the flu does not need to be excluded if staff can care for them and all of the other children and they feel well enough to participate.

Avoiding Spreading Germs to Others

Early care and education programs should teach children and model good cough and sneeze etiquette. Always sneeze or cough into a tissue that is discarded after use. If a tissue is not available, use your upper sleeve, completely covering the mouth and nose. Always wash hands after coughing, sneezing, and blowing noses.[11]

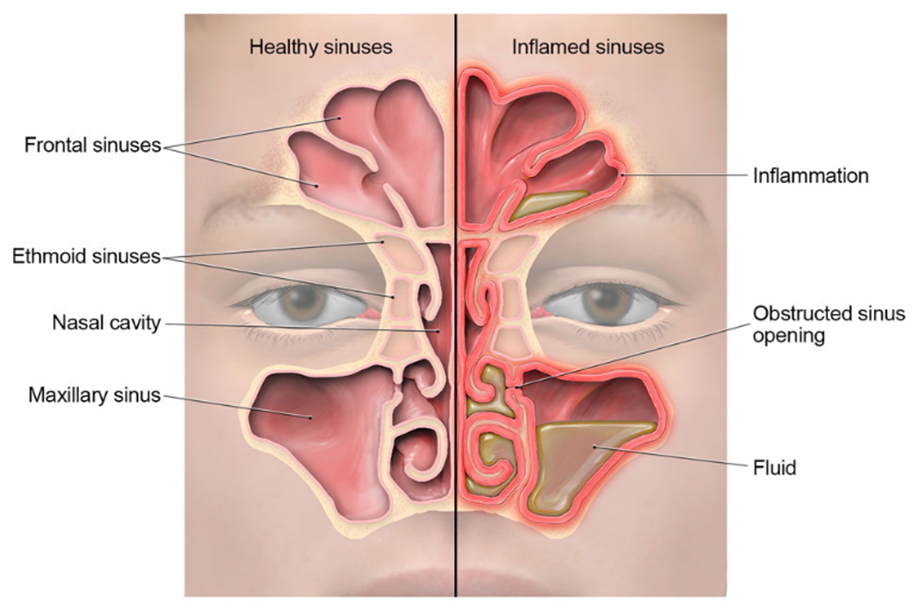

Sinusitis (Sinus Infection)

Sinus infections happen when fluid builds up in the air-filled pockets in the face (sinuses), which allows germs to grow. Viruses cause most sinus infections, but bacteria can cause some sinus infections.

Common symptoms of sinus infections include:

- Runny nose

- Stuffy nose

- Facial pain or pressure

- Headache

- Mucus dripping down the throat (post-nasal drip)

- Sore throat

- Cough

- Bad breath

Most sinus infections usually get better on their own without antibiotics. As with colds and flu, a child does not need to be automatically excluded from care for a sinus infection.[14]

Pause to Reflect

| What was your last experience with an upper respiratory infection (such as a cold, flu, or sinus infection? If a child had the same symptoms as you, would they have needed to be excluded from care? |

Sore Throat

A sore throat can make it painful to swallow. A sore throat can also feel dry and scratchy. A sore throat can be a symptom of the common cold, allergies, strep throat, or other upper respiratory tract illnesses. Strep throat is an infection in the throat and tonsils caused by bacteria called group A Streptococcus (also called Streptococcus pyogenes).

Infections from viruses are the most common cause of sore throats. The following symptoms suggest a virus is the cause of the illness instead of the bacteria called group A strep:

- Cough

- Runny nose

- Hoarseness (changes in your voice that makes it sound breathy, raspy, or strained)

- Conjunctivitis (also called pink eye)

The most common symptoms of strep throat include:

- Sore throat that can start very quickly

- Pain when swallowing

- Fever

- Red and swollen tonsils, sometimes with white patches or streaks of pus

- Tiny red spots on the roof of the mouth

- Swollen lymph nodes in the front of the neck

A doctor can determine the likely cause of a sore throat. If a sore throat is caused by a virus, antibiotics will not help. Most sore throats will get better on their own within one week and are not cause for exclusion from child care.

Since bacteria cause strep throat, antibiotics are needed to treat the infection and prevent rheumatic fever and other complications. A doctor cannot tell if someone has strep throat just by looking in the throat. If a doctor suspects strep throat, they may test to confirm the diagnosis. A child with strep throat should be excluded from care until they no longer have a fever AND have taken antibiotics for at least 24 hours.[15]

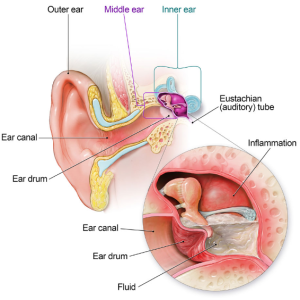

Ear Infection

There are different types of ear infections. Middle ear infection (acute otitis media) is an infection in the middle ear.

Another condition that affects the middle ear is called otitis media with effusion. It occurs when fluid builds up in the middle ear without being infected and without causing fever, ear pain, or pus build-up in the middle ear.

When the outer ear canal is infected, the condition is called swimmer’s ear, which is different from a middle ear infection.

Middle Ear Infection

A middle ear infection may be caused by:

- Bacteria, like Streptococcus pneumonia and Haemophilus influenza (non-typeable) – the two most common bacterial causes

- Viruses, like those that cause colds or flu

Common symptoms of middle ear infection in children can include:

- Ear pain

- Fever

- Fussiness or irritability

- Rubbing or tugging at an ear

- Difficulty sleeping

A doctor can make the diagnosis of a middle ear infection by looking inside the child’s ear to examine the eardrum and see if there is pus in the middle ear. Antibiotics are often not needed for middle ear infections because the body’s immune system can fight off the infection on its own. However, sometimes antibiotics, such as amoxicillin, are needed to treat severe cases right away or cases that last longer than 2–3 days.[17]

Swimmer’s Ear

Ear infections can be caused by leaving contaminated water in the ear after swimming. This infection, known as “swimmer’s ear” or otitis externa, is not the same as the common childhood middle ear infection. The infection occurs in the outer ear canal and can cause pain and discomfort for swimmers of all ages.

Symptoms of swimmer’s ear usually appear within a few days of swimming and include:

- Itchiness inside the ear.

- Redness and swelling of the ear.

- Pain when the infected ear is tugged or when pressure is placed on the ear.

- Pus draining from the infected ear.

Although all age groups are affected by swimmer’s ear, it is more common in children and can be extremely painful. If swimmer’s ear is suspected, a healthcare provider should be consulted. Swimmer’s ear can be treated with antibiotic ear drops.[18]

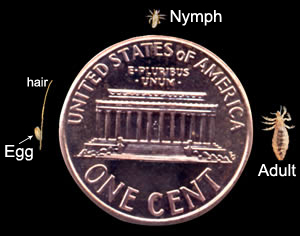

Head Lice

Head lice are parasitic insects that live on the head. They survive by feeding on human blood. Lice infestations are spread most commonly by close person-to-person contact. Lice move by crawling; they cannot hop or fly.

Adult head lice are 2–3 mm in length. Head lice infest the head and neck and attach their eggs to the base of the hair shaft. Lice move by crawling; they cannot hop or fly.[19]

Symptoms of a head lice infestation include:

- Tickling feeling of something moving in the hair.

- Itching is caused by an allergic reaction to the bites of the head louse.

- Irritability and difficulty sleeping; head lice are most active in the dark.

- Sores on the head caused by scratching. These sores can sometimes become infected with bacteria found on the person’s skin.

Head-to-head contact with a person who already has an infestation is the most common way to get head lice. Head-to-head contact is common during play at school, at home, and elsewhere (sports activities, playground, slumber parties, camp).

Although uncommon, head lice can be spread by sharing clothing or belongings. This happens when lice crawl, or the nits that are attached to shed hair hatch, and get on the shared clothing or belongings. Examples include:

- Sharing clothing (hats, scarves, coats, sports uniforms) or articles (hair ribbons, barrettes, combs, brushes, towels, stuffed animals) recently worn or used by a person with an infestation;

- Or lying on a bed, couch, pillow, or carpet that has recently been in contact with a person with an infestation.

Dogs, cats, and other pets do not play a role in the spread of head lice.

The diagnosis of a head lice infestation is best made by finding a live nymph or adult louse on the scalp or hair of a person. Because nymphs and adult lice are very small (about the size of a sesame seed), move quickly, and avoid light, they can be difficult to find. The use of a magnifying lens and a fine-toothed comb may be helpful in finding live lice. Live lice are tan to greyish-white.

If crawling lice are not seen, finding nits firmly attached within a ¼ inch of the base of the hair shafts strongly suggests, but does not confirm, that a person is infested and should be treated. Nits that are attached more than ¼ inch from the base of the hair shaft are almost always dead or already hatched. Nits are often confused with other things found in the hair such as dandruff, hair spray droplets, and dirt particles. If no live nymphs or adult lice are seen, and the only nits found are more than ¼-inch from the scalp, the infestation is probably old and no longer active and does not need to be treated.[21]

Treatment for head lice is recommended for persons diagnosed with an active infestation. All household members and other close contacts should be checked; those persons with evidence of an active infestation should be treated with an over-the-counter or prescription medication (following the provided instructions).

Hats, scarves, pillowcases, bedding, clothing, and towels worn or used by the person with the infestation in the 2-day period just before treatment is started can be machine washed and dried using the hot water and hot air cycles because lice and eggs are killed by exposure for 5 minutes to temperatures greater than 128.3°F. Items that cannot be laundered may be dry-cleaned or sealed in a plastic bag for two weeks. Items such as hats, grooming aids, and towels that come in contact with the hair of a person with an infestation should not be shared. Vacuuming furniture and floors can remove hairs that might have viable nits attached. Head lice do not survive long if they fall off a person and cannot feed.

After treatment, it’s important to check the hair and comb with a nit comb to remove nits and lice every 2–3 days which will decrease the chance of self–reinfestation. Checking for 2–3 weeks will ensure that all lice and nits are gone.[23]

Children with head lice should be treated and can attend child care as usual.

No More “No Nits” Policies

Children diagnosed with live head lice do not need to be sent home early from early care and education programs or school; they can go home at the end of the day, be treated, and return to class after appropriate treatment has begun. Nits may persist after treatment, but successful treatment should kill crawling lice.

Head lice can be a nuisance but they have not been shown to spread disease. Personal hygiene or cleanliness in the home or school has nothing to do with getting head lice.

No-nits policies are not necessary and can have a negative impact on the child and the families:

- The presence of nits indicates a past infestation, that may not be currently active

- Head lice are very common among young children

- Head lice do not spread diseases

- Head lice is often misdiagnosed

- Children can have head lice for several weeks without symptoms.

- Not all parents can financially or time-wise afford to take time off if their child is excluded.

Pause to Reflect

| What experience with or knowledge do you have about policies that specific early education and care programs and schools have on head lice? Are (or were) those policies “no nits” or in line with the recommendations above? |

Illnesses

The Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) has developed a useful chart that outlines the following:

- The illness

- how it is transmitted,

- sign/symptoms,

- infectious period,

- whether to exclude or not, and

- whether to report or not.

Click on the CPS logo to view the chart. The chart can also be found in Appendix J: Illnesses

Danger of Infectious Disease for Adults

| Because early care and education program employees are around children who are at higher risk of infectious diseases and have limited understanding of hygiene practices, those employees are also at greater risk of getting sick.

While most illnesses that are spread in early care and education programs are not serious, some can be very dangerous. Knowledge about illness and how to prevent its spread helps. Being fully immunized (from childhood illness and or vaccines) protects adult health as well. Employees who are or could become pregnant want to be especially careful because first-time exposure to:

Each can cause major damage to fetal health, birth defects, and even fetal death.[24] See Appendix J: Illnesses for more details on these illnesses or click here |

Reportable Diseases

Some diseases are enough of a threat to the community that it is required that diagnosed cases are reported to the local health department. According to the Public Health Act 1994, the following communicable diseases need to be reported right away. Click on the Government of Saskatchewan Logo to view the list. The list can also be found in Appendix J: illnesses.

Exclusion Policies

Most children with mild illnesses can safely attend child care. “Many health policies concerning the care of ill children [including exclusion policies] have been based upon common misunderstandings about contagion, risks to ill children, and risks to other children and staff. Current research clearly shows that certain ill children do not pose a health threat. Also, the research shows that keeping certain other mildly ill children at home or isolated in the child care setting will not prevent other children from becoming ill.”[25]

But there are times when exclusion is the right answer. Excluding a child from the child care setting should only be considered when:

- It is a category I or II illness – For additional information about category I or II illnesses, visit the Public Health Act (1994)

- The child does not feel well enough to participate comfortably in the program’s activities.

- The staff cannot adequately care for the sick child without compromising the care of the other children.

- The child has any of the following symptoms:

- Fever (above 100° F. axillary or above 101° F. orally) accompanied by behaviour change and other signs or symptoms of illness (i.e., the child looks and acts sick)

- Signs or symptoms of possibly severe illness (e.g., persistent crying, extreme irritability, uncontrolled coughing, difficulty breathing, wheezing, lethargy)

- Diarrhea: Changes from the child’s usual stool pattern–increased frequency of stools, looser/watery stools, stool runs out of the diaper, or the child can’t get to the bathroom in time.

- Vomiting more than once in the previous 24 hours

- Rash with a fever or behavior change

The child should be excluded if they have any of the following diagnoses from a health provider (until treated and/or no longer contagious):

-

- Infectious conjunctivitis/pink-eye (with eye discharge)-until 24 hours after treatment started

- Scabies, head lice, or other infestation until 24 hours after treatment and free of nits.

- Impetigo-until 24 hours after treatment started

- Strep throat, scarlet fever, or other strep infection until 24 hours after treatment started and the child is free of fever

- Pertussis-until five days after treatment started (if determined by the public health authorities)

- Tuberculosis (TB)-until a health care provider determines that the disease is not contagious (at least 2 weeks)

- Mumps – for 5 days after onset of swelling of cheeks.

- Hepatitis A – 1 week after start of symptoms (e.g., jaundice)

- Measles – at least 4 days after the start of the rash

- Rubella (German measles) – for 7 days after the start of the rash.[26]

If there is an outbreak of any reportable illness (See Table 9.2), a child or staff member who meets the following criteria as determined by the local health department or a health care provider, should be excluded:

- contributing to the transmission of the illness

- not adequately immunized when the disease is vaccine-preventable

- at increased risk due to the pathogens being circulated.

They can be readmitted when the health department official or that health care provider decides that the risk of transmission is no longer present.[27] For more detailed information about illnesses that should be excluded visit the Infection control manual for child care facilities Appendix A: Chart of Some Common Communicable Diseases

What to do When a Child Requires Exclusion

When a child becomes ill enough to be excluded, they should be immediately isolated from other children. Early care and education programs are required to be equipped to isolate and care for any child who becomes ill during the day. The isolation area shall be located to afford easy supervision of children by center staff and equipped with a mat, cot, couch or bed for each ill child (or a crib if caring for infants).

The child’s parent(s) shall be notified immediately when the child becomes ill enough to require isolation and shall be asked to have the child picked up from the center as soon as possible. For more detailed information about illnesses that should be excluded visit the Infection control manual for child care facilities Appendix A: Chart of Some Common Communicable Diseases [footnote]Infection Control Manual for Day Care Providers: Appendix A: Chart of Some Common Communicable Diseases by Government of Saskatchewan, in the public domain.[/footnote]

Caring for Mildly Ill Children

Because young in early care and education programs have a high incidence of illness and may have conditions (such as eczema and asthma), providers should be prepared to care for mildly ill children, at least temporarily. And since we know that excluding most mildly ill children doesn’t prevent the spread of illness and can have negative effects on families, programs should consider whether they can care for children with mild symptoms (not meeting the exclusion policy). The California Childcare Health Program poses the following questions to consider:

- Are there sufficient staff (including volunteers) to provide minor modifications that a child might need (such as quiet activities or extra fluids)?

- Are staff willing and able to care for the child’s symptoms (such as wiping a runny nose and checking a fever) without neglecting the care of other children in the group?

- Is there a space where the mildly ill child can rest if needed?

- Have families made alternative arrangements for someone to pick up and care for their ill children if they cannot?”

It’s important that programs recognize that families have to weigh many things when trying to decide whether or not to send a child to child care. They must consider how the child feels (physically and emotionally), whether or not the program can provide care for the specific needs of the child, what alternative care arrangements are available, as well as the income they may lose if they have to stay home.[28]

Responding to Illness that Requires Medical Care

“Some conditions, require immediate medical help. If the parents can be reached, tell them to come right away and notify their medical provider.

Call Emergency Medical Services (9-1-1) immediately and also notify parents if any of the following things happen:

- You believe a child needs immediate medical assessment and treatment that cannot wait for parents to take the child for care.

- A child has a stiff neck (that limits his ability to put his chin to his chest) or severe headache and fever.

- A child has a seizure for the first time.

- A child who has a fever as well as difficulty breathing.

- A child looks or acts very ill, or seems to be getting worse quickly.

- A child has skin or lips that look blue, purple or gray.

- A child is having difficulty breathing or breathing so fast or hard that he or she cannot play, talk, cry or drink.

- A child who is vomiting blood.

- A child complains of a headache or feeling nauseous, or is less alert or more confused, after a hard blow to the head.

- Multiple children have injuries or serious illnesses at the same time.

- A child has a large volume of blood in the stools.

- A child has a suddenly spreading blood-red or purple rash.

- A child acts unusually confused.

- A child is unresponsive or has decreasing responsiveness.

Call the parent to come right away, and get medical help immediately, when any of the following things happen. If the parent or the child’s medical provider is not immediately available, call 9-1-1 (EMS) for immediate help:

- A fever in any child who appears more than mildly ill.

- An infant under 2 months of age has an axillary (“armpit”) temperature above 100.4º F.

- An infant under four months of age has two or more forceful vomiting episodes (not the simple return of swallowed milk or spit-up) after eating.

- A child has neck pain when the head is moved or touched.

- A child has a severe stomach ache that causes the child to double up and scream.

- A child has a stomach ache without vomiting or diarrhea after a recent injury, blow to the abdomen or hard fall.

- A child has stools that are black or have blood mixed through them.

- A child has not urinated in more than eight hours, and the mouth and tongue look dry.

- A child has continuous, clear drainage from the nose after a hard blow to the head.

- A child has a medical condition outlined in his special care plan as requiring medical attention.

- A child has an injury that may require medical treatment such as a cut that does not hold together after it is cleaned.”[29]

Administering Medications

Some children in your early care and education setting may need to take medications during the hours you provide care for them. Early care and education programs must have a written policy for the use of prescription and nonprescription medication.[30]

The Child Care Regulations, 2015

PART III – STANDARDS FOR FACILITIES – DIVISION 3 – HEALTH AND SAFETY

MEDICATIONS

Section 26

If a licensee has reason to suspect that a child attending the facility has a category I or category II communicable disease, the licensee must:

(a) immediately notify the public health officer, and

(b) ensure that any recommendations or instructions of the public health officer with respect to that communicable disease that may affect the health or well-being of a child attending the facility are carried out. 22 May 2015 cC-7.31 Reg 1 s26.

Section 27

(1) A licensee who agrees to administer a medication to a child attending the facility must:

(a) subject to subsection (2), obtain written authorization, on a form supplied by the ministry, from the parent of the child before the medication is administered to the child;

(b) ensure that a written record of each dose of medication administered to the child is made on a form supplied by the ministry and maintained in accordance with section 36; and

(c) ensure that all non-emergency medications are stored in a locked enclosure. 22 May 2015 cC-7.31 Reg 1 s27.

According to licensing, programs that choose to handle medications must abide by the following:

- All prescription and nonprescription medications shall be centrally stored in a safe place inaccessible to children, with an unaltered label, and labelled with the child’s name and date

- A refrigerator shall be used to store any medication that requires refrigeration.

- Prescription medications may be administered with written permission by the child’s authorized representatives in accordance with the label instructions by the physician

- Nonprescription medications may be administered without approval or instructions from the child’s physician with written approval and instructions from the child’s authorized representative and when administered in accordance with the product label directions.

Valid reasons for an early care and education program to consider administering medication.

- Some medication dosing cannot be adjusted to be taken before and after care (and keeping them out of care when otherwise well enough to attend, would be a hardship for families.

- Some children may have chronic conditions that may require urgent administration of medication (such as asthma and diabetes).[32]

Communication with Families

When children are excluded from care, it’s important to provide documentation for families of how the child meets the guidelines in your exclusion policy and what needs to happen before the child can return to care. See Appendix K for a possible form that programs could use.

Programs are also required to inform families when children are exposed to a communicable disease. See Appendix L for an example of a notice of exposure form you can provide to families so they know what signs of illness to watch for and to seek medical advice when necessary.[33]

Pause to Reflect

|

Why is it important for early care and education programs to communicate clearly with families regarding communicable illness? |

Summary

Becoming familiar with infectious diseases that are common in early childhood enables early care and education program staff to identify illness and respond appropriately. This included knowing when children (and staff) should be excluded from care and what needs to happen before they should come back.

Programs must create policies on how they will handle children that are mildly ill (those that need care before they can be picked up from care and those that do not require exclusion) and children who have illness that requires medical care. Programs who choose to administer medication, must be familiar with the licensing regulations they must follow.

Open communication with families is important when a child becomes ill or is potentially exposed to an illness. Helping families understand and follow policies regarding exclusion is vital to keeping everyone in the program as healthy as possible.

Resources for Further Exploration

· Health and Safety in the Child Care Setting: Prevention of Infectious Disease A Curriculum for the Training of Child Care Providers: https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/idc2book.pdf

· A Quick Guide to Common Childhood Diseases (Canadian resource): bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Guidelines%20and%20Forms/Guidelines%20and%20Manuals/Epid/Other/Epid_GF_childhood_quickguide_may_09.pdf

· Common Childhood Infections – A Guide for Principals, Teachers and Child Care Providers (Canadian resource): https://www.tbdhu.com/sites/default/files/files/resource/2017-03/Common%20Childhood%20Infections%20Manual_0.pdf

· Georgia School Resource Health Manual: https://www.choa.org/~/media/files/Childrens/medical-professionals/nursing-resources/ch-4-communicable-diseases-and-infection-control.pdf?la=en

· Diseases & Conditions A-Z Index: https://www.cdc.gov/diseasesconditions/az/a.html

· Childhood Infectious Illnesses: http://www.ocwtp.net/PDFs/Trainee%20Resources/Preservice/Session10DiseaseChartOption.pdf

· Appropriate Antibiotic Use: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/community/index.html

· When to Keep Your Child Home from Child Care: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/family-life/work-play/Pages/When-to-Keep-Your-Child-Home-from-Child-Care.aspx

References

- Image by College of the Canyons ZTC Team is based on the image from Managing Infectious Disease in Head Start Webinar by Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center, which is in the public domain ↵

- Infectious Diseases: Prevention and Management by Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center is in the public domain ↵

- Image by College of the Canyons ZTC Team is based on the image from Managing Infectious Disease in Head Start Webinar by Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center, which is in the public domain ↵

- Image by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Common Cold by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Common Cold by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Symptoms of Influenza by Mikael Häggström is in the public domain. ↵

- Flu Symptoms & Complications by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Influenza (Flu) Preventive Steps by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Flu Treatment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Image by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Common Colds: Protect Yourself and Others by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Image by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Sinus Infection (Sinusitis) by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Sore Throat by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Image by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Ear Infection by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Healthy Swimming: Ear Infections by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Parasites – Lice by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Image by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Head Lice: FAQ by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Image by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- Head Lice: Treatment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- California Child Care Health Program. (2011). Health and Safety in the Child Care Setting: Prevention of Infectious Disease. University of California San Francisco. Retrieved from https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/idc2book.pdf ↵

- California Childcare Health Program. (2018). Preventive Health and Safety in the Child Care Setting: A Curriculum for the Training of Child Care Providers (3rd ed.). University of California, San Francisco. Retrieved from https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/PHT-Handbook-Student-2018-FINAL.pdf ↵

- Infection Control Manual for Day Care Providers: Appendix A: Chart of Some Common Communicable Diseases by Government of Saskatchewan, in the public domain. ↵

- Infection Control Manual for Child Care Facilities: Appendix A: Chart of Some Common Communicable Diseases by Government of Saskatchewan, in the public domain. ↵

- California Childcare Health Program. (2018). Preventive Health and Safety in the Child Care Setting: A Curriculum for the Training of Child Care Providers (3rd ed.). University of California, San Francisco. Retrieved from https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/PHT-Handbook-Student-2018-FINAL.pdf ↵

- California Childcare Health Program. (2018). Preventive Health and Safety in the Child Care Setting: A Curriculum for the Training of Child Care Providers (3rd ed.). University of California, San Francisco. Retrieved from https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/PHT-Handbook-Student-2018-FINAL.pdf ↵

- Child Care Regulations, 2015, C-7.31 Reg 1, Goverenment of Saskatchewan, in the public domain ↵

- Close-up of a woman pours a spoon of medicinal mixture by Marco Verch is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- California Childcare Health Program. (2018). Preventive Health and Safety in the Child Care Setting: A Curriculum for the Training of Child Care Providers (3rd ed.). University of California, San Francisco. Retrieved from https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/PHT-Handbook-Student-2018-FINAL.pdf ↵

- California Childcare Health Program. (2018). Preventive Health and Safety in the Child Care Setting: A Curriculum for the Training of Child Care Providers (3rd ed.). University of California, San Francisco. Retrieved from https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/PHT-Handbook-Student-2018-FINAL.pdf ↵