Chapter 12: Basic Nutrition for Children

Read Time: 46 mins

Factors Affecting Eating Habits

Factors that Drive Food Choices

Emergence of Canada’s New Food Guide

Why should you care about the Canada Food Guide?

The Nutrition Facts Table and Ingredient List

Regulations Relating to Nutrition

Section 24

References

Chapter 12: Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define and explain the function of each macronutrient and type of micronutrient.

- Examine factors that affect the quality of food.

- Discuss influences on food choice.

- Outline how to achieve a healthy diet.

Introduction

To plan, prepare, and serve nutritious foods to children in early care and education programs it’s important to have a basic understanding of nutrition and the programs and resources available to support meeting children’s nutrition needs.

What are Nutrients?

The foods we eat contain nutrients. Nutrients are substances required by the body to perform its basic functions. Nutrients must be obtained from our diet since the human body does not synthesize or produce them. Nutrients have one or more of three basic functions: they provide energy, contribute to body structure, and/or regulate chemical processes in the body. These basic functions allow us to detect and respond to environmental surroundings, move, excrete wastes, respire (breathe), grow, and reproduce. There are six classes of nutrients required for the body to function and maintain overall health. These are carbohydrates, fats, proteins, water, vitamins, and minerals. Foods also contain non-nutrients that may be harmful (such as natural toxins common in plant foods and additives like some dyes and preservatives) or beneficial (such as antioxidants).

Macronutrients

Nutrients that are needed in large amounts are called macronutrients. There are three classes of macronutrients: carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. These can be metabolically processed into cellular energy, allowing our bodies to conduct their basic functions. A unit of measurement of food energy is the calorie. Water is also a macronutrient in the sense that you require a large amount of it, but unlike the other macronutrients, it does not yield calories.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are molecules composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. The major food sources of carbohydrates are grains, milk, fruits, and starchy vegetables, like potatoes. Non-starchy vegetables also contain carbohydrates but in lesser quantities. Carbohydrates are broadly classified into two forms based on their chemical structure: simple carbohydrates, often called simple sugars; and complex carbohydrates.

Simple carbohydrates consist of one or two basic units. Examples of simple sugars include sucrose, the type of sugar you would have in a bowl on the breakfast table, and glucose, the type of sugar that circulates in your blood.

Complex carbohydrates are long chains of simple. During digestion, the body breaks down digestible complex carbohydrates into simple sugars, mostly glucose. Glucose is then transported to all our cells where it is stored, used to make energy, or used to build macromolecules. Fibre is also a complex carbohydrate, but it cannot be broken down by digestive enzymes in the human intestine. As a result, it passes through the digestive tract undigested unless the bacteria that inhabit the colon or large intestine break it down.

One gram of digestible carbohydrates yields four kilocalories of energy for the cells in the body to perform work. In addition to providing energy and serving as building blocks for bigger macromolecules, carbohydrates are essential for the proper functioning of the nervous system, heart, and kidneys. As mentioned, glucose can be stored in the body for future use.

Fats

Fat (officially called lipids) are also a family of molecules composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, but unlike carbohydrates, they are insoluble in water. Fats are found predominantly in butter, oils, meats, dairy products, nuts, and seeds, and in many processed foods. The main job of fats is to provide or store energy. Fats provide more energy per gram than carbohydrates (nine kilocalories per gram of fats versus four kilocalories per gram of carbohydrates). In addition to energy storage, fats serve as a major component of cell membranes, surround and protect organs (in fat-storing tissues), provide insulation to aid in temperature regulation and regulate many other functions in the body.

Proteins

Proteins are macromolecules composed of chains of subunits called amino acids. Amino acids are simple subunits composed of carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen. Food sources of proteins include meats, dairy products, seafood, and a variety of different plant-based foods, most notably soy. The word protein comes from a Greek word meaning “of primary importance,” which is an apt description of these macronutrients; they are also known colloquially as the “workhorses” of life. Proteins provide four kilocalories of energy per gram; however, providing energy is not protein’s most important function. Proteins provide structure to bones, muscles and skin, and play a role in conducting most of the chemical reactions that take place in the body. Scientists estimate that more than one hundred thousand different proteins exist within the human body. The genetic codes in DNA are basically protein recipes that determine the order in which 20 different amino acids are bound together to make thousands of specific proteins.

Water

There is one other nutrient that we must have in large quantities: water. Water does not contain carbon, but is composed of two hydrogens and one oxygen per molecule of water. More than 60 percent of your total body weight is water. Without it, nothing could be transported in or out of the body, chemical reactions would not occur, organs would not be cushioned, and body temperature would fluctuate widely.

|

Protein |

Carbohydrates |

Fats |

Water |

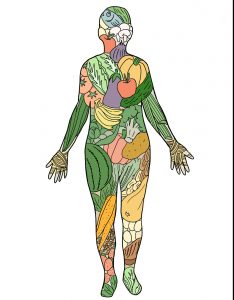

Figure 12.1 – The Macronutrients: Carbohydrates, Fats, Protein, and Water[1]

Micronutrients

Micronutrients are nutrients required by the body in lesser amounts but are still essential for carrying out bodily functions. Micronutrients include all the essential minerals and vitamins. There are sixteen essential minerals and thirteen vitamins (See Table 12.1 “Minerals and Their Major Functions” and Table 12.2 “Vitamins and Their Major Functions” for a complete list and their major functions). In contrast to carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, micronutrients are not sources of energy (calories), but they assist in the process as components of enzymes. Enzymes are proteins that cause chemical reactions in the body and are involved in all aspects of body functions from producing energy to digesting nutrients to building macromolecules. Micronutrients play many essential roles in the body.

Minerals

Minerals are solid inorganic substances that form crystals and are classified depending on how much of them we need. Trace minerals, such as molybdenum, selenium, zinc, iron, and iodine, are only required in a few milligrams or less. Macrominerals, such as calcium, magnesium, potassium, sodium, and phosphorus, are required in hundreds of milligrams. Many minerals are critical for enzyme function, others are used to maintain fluid balance, build bone tissue, synthesize hormones, transmit nerve impulses, contract and relax muscles, and protect against harmful free radicals in the body that can cause health problems such as cancer.

Table 12.1 – Minerals and Their Major Functions[2]

Major Minerals

| Major Mineral | Major Function |

| Sodium | Fluid balance, nerve transmission, muscle contraction |

| Chloride | Fluid balance, stomach acid production |

| Potassium | Fluid balance, nerve transmission, muscle contraction |

| Calcium | Bone and teeth health maintenance, nerve transmission, muscle contraction, blood clotting |

| Phosphorus | Bone and teeth health maintenance, acid-base balance |

| Magnesium | Protein production, nerve transmission, muscle contraction |

| Sulfur | Protein production |

Trace Minerals

| Trace Minerals | Major Functions |

| Iron | Carries oxygen, assists in energy production |

| Zinc | Protein and DNA production, wound healing, growth, immune system function |

| Iodine | Thyroid hormone production, growth, metabolism |

| Selenium | Antioxidant |

| Copper | Coenzyme, iron metabolism |

| Manganese | Coenzyme |

| Fluoride | Bone and teeth health maintenance, tooth decay prevention |

| Chromium | Assists insulin in glucose metabolism |

| Molybdenum | Coenzyme |

Vitamins

The thirteen vitamins are categorized as either water-soluble or fat-soluble. The water-soluble vitamins are vitamin C and all the B vitamins, which include thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, pantothenic acid, pyridoxine, biotin, folate and cobalamin. Unneeded water-soluble vitamins are excreted from the body. The fat-soluble vitamins are A, D, E, and K. Vitamins are required to perform many functions in the body such as making red blood cells, synthesizing bone tissue, and playing a role in normal vision, nervous system function, and immune system function. Fat-soluble vitamins are stored in the body in fat (and can become toxic when too much is consumed, almost always from supplements).

Table 12.2 – Vitamins and Their Major Functions[3]

Water Soluble

| Vitamin | Major Function |

| Thiamin (B1) | Coenzyme, energy metabolism assistance |

| Riboflavin (B2 ) | Coenzyme, energy metabolism assistance |

| Niacin (B3) | Coenzyme, energy metabolism assistance |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | Coenzyme, energy metabolism assistance |

| Pyridoxine (B6) | Coenzyme, amino acid synthesis assistance |

| Biotin (B7) | Coenzyme, amino acid and fatty acid metabolism |

| Folate (B9) | Coenzyme, essential for growth |

| Cobalamin (B12) | Coenzyme, red blood cell synthesis |

| C (ascorbic acid) | Collagen synthesis, antioxidant |

Fat Soluble

| Vitamin | Major Function |

| A | Vision, reproduction, immune system function |

| D | Bone and teeth health maintenance, immune system function |

| E | Antioxidant, cell membrane protection |

| K | Bone and teeth health maintenance, blood clotting |

Vitamin deficiencies can cause severe health problems and even death. Some vitamins have been found to prevent certain disorders and diseases such as scurvy (vitamin C), night blindness (vitamin A), and rickets (vitamin D).[4]

Table 12.3 – Summary of the Functions of Nutrients[5]

| Name of Nutrient | Description of Function |

| Protein | Necessary for tissue formation, cell reparation, and hormone and enzyme production. It is essential for building strong muscles and a healthy immune system. |

| Carbohydrates | Provide a ready source of energy for the body and provide structural constituents for the formation of cells. |

| Fat | Provides stored energy for the body, functions as structural components of cells and also as signaling molecules for proper cellular communication. It provides insulation to vital organs and works to maintain body temperature. |

| Vitamins | Regulate body processes and promote normal body-system functions. |

| Minerals | Regulate body processes, are necessary for proper cellular function, and comprise body tissue. |

| Water | Transports essential nutrients to all body parts, transports waste products for disposal, and aids with body temperature maintenance. |

Quality of Food

Nutrient-dense foods One measurement of food quality is the amount of nutrients it contains relative to the amount of energy it provides. High-quality foods are nutrient-dense, meaning they contain significant amounts of one or more essential nutrients relative to the amount of calories they provide.

“Empty” Calories Nutrient-dense foods are the opposite of “empty-calorie” foods such as carbonated sugary soft drinks, which provide many calories and very little if any, other nutrients. Food quality is additionally associated with its taste, texture, appearance, microbial content, and how much consumers like it.[6]

Food: A Better Source of Nutrients

It is better to get all your micronutrients from the foods you eat as opposed to from supplements. Supplements contain only what is listed on the label, but foods contain many more macronutrients, micronutrients, and other chemicals, like antioxidants, that benefit health. While vitamins, multivitamins, and supplements are a huge money-making industry, there is no consistent evidence that they are better than food in promoting health and preventing disease.[7]

Food Additives

People have been using food additives for thousands of years, but certainly not to the level that is used today in the typical Canadian diet. Today more than 3000 substances are used as food additives. Salt, sugar, and corn syrup are by far the most widely used additives. How this might affect the quality (including nutritional value) of food will depend on the additive and the person’s individual risk factors such as allergies, intolerances, etc.

Figure 12.4 – Food Additives

Salt[8] |

Sugar[9] |

Food coloring[10] |

Food additives are regulated under the Food and Drug Regulations (FDR). According to Health Canada, “Food additive” is defined as”… any chemical substance that is added to food during preparation or storage and either becomes a part of the food or affects its characteristics for the purpose of achieving a particular technical effect”[11]

In addition “Substances that are used in food to maintain its nutritive quality, enhance its keeping quality, make it attractive or to aid in its processing, packaging or storage are all considered to be food additives”[12]

| Type of Food Additive | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Coloring Agents | gives food an appetizing appearance |

| Anticaking Agents | keeps powers "free-running" (i.e. salt or brown sugar) |

| Preservatives | Prevent or delay undesirable spoilage in foods |

| Certain Sweeteners | Sweeten foods without significantly adding to the caloric value. |

| Food additives do not include: | |

| Food ingredients (i.e. salt, sugar, starch | |

| Vitamins, minerals, amino acid | |

| Spices, seasoning, flavoring preparations | |

| Agricultural chemicals. | |

| Veterinary drugs | |

| Food packing materials. | |

The FDR, in association with Marketing Authorizations (MA), regulates what can and can not be used as an additive. According to Health Canada (2023), “… food additives must comply with specifications set out in the Food Chemical Codex (FCC) or the specification of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA)”[13]

Food Colouring

Health Canada refers to food colouring as a colouring agent, which is defined as “… a food additive that is used to add or restore colour to a food”. Colouring agents are regulated under the Food and Drug Regulations (FDR).

Colour agents are used in foods for many reasons:

- To offset colour loss due to exposure to light, air, temperature extremes, moisture, and storage conditions;

- To correct natural variations in colour;

- To enhance colours that occur naturally; and

- To provide colour to colourless and “fun” foods.

Without colour additives, margarine wouldn’t be yellow, and mint ice cream wouldn’t be green. Colour agents are now recognized as an important part of practically all processed foods we eat.

Today, food and colour additives are more strictly studied, regulated, and monitored than at any other time in history. Canadian Food Inspection Agency has the primary responsibility for determining their safe use. To market a new food or colour agent (or before using an additive already approved for one use in another manner not yet approved), a manufacturer or other sponsor must first file a food additive submission with Health Canada. These submissions must provide evidence that the substance is safe for the ways in which it will be used.

As of December 2021, food agents can no longer be referred to as simply “colour” on a food label, instead, they must use their specific common name in the list of ingredients – making Canada’s food label one of the most transparent in the world. The new labelling also helps consumers make clearer choices about the foods they eat.

Artificial Sweeteners

Artificial sweeteners, also called sugar substitutes, are substances that are used instead of sucrose (table sugar) to sweeten foods and beverages. Because artificial sweeteners are many times sweeter than table sugar, much smaller amounts (200 to 20,000 times less) are needed to create the same level of sweetness.

Artificial sweeteners are regulated by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). Some common artificial sweeteners that are approved in Canada are:

- Aspartame, distributed under several trade names (e.g., NutraSweet®and Equal®),

- Sucralose, marketed under the trade name Splenda®

- Acesulfame potassium (also known as ACK, Sweet One®, and Sunett®)

- Neotame, which is similar to aspartame

- Advantame, which is also similar to aspartame

- A complete list can be found on the Canada.ca website under List of permitted sweeteners

Questions about artificial sweeteners and cancer arose when early studies showed that cyclamate in combination with saccharin caused bladder cancer in laboratory animals. However, results from subsequent carcinogenicity studies (studies that examine whether a substance can cause cancer) of these sweeteners have not provided clear evidence of an association with cancer in humans. Similarly, studies of other FDA-approved sweeteners have not demonstrated clear evidence of an association with cancer in humans.[15] Please note that even if artificial sweeteners have not been shown to cause cancer, it is NOT recommended for use, especially with children. The research on this has been relatively limited and is not conclusive.

Factors Affecting Eating Habits.

Many people believe that factors such as environment and lifestyle are the only things that influence the foods you choose to eat. In fact, there are several factors that affect our eating habits. Different foods affect energy level, mood, how much is eaten, how long before you eat again, and if cravings are satisfied. We have talked about some of the physical effects of food on your body, but there are other effects too.

Food regulates your appetite and how you feel – ever heard about being “Hangry?” (being angry because you are hungry). Multiple studies have demonstrated that some high-fibre foods and high-protein foods decrease appetite by slowing the digestive process and prolonging the feeling of being full or satiety. The effects of individual foods and nutrients on mood are not backed by consistent scientific evidence, but in general, most studies support that healthier diets are associated with a decrease in depression and improved well-being. To date, science has not been able to track the exact path in the brain that occurs in response to eating a particular food, but it is quite clear that foods, in general, stimulate emotional responses in people.

Physical

We need food to live. Food is the building block for cell and tissue growth. The variations of body types depend on not only genetics but also what we eat; “we are what we eat”. As we will see eating habits are not that easy, there are many other factors.

Emotional

Our eating habits are also influenced or affected by our emotions. The first aspect of emotion and eating relates to what we like and don’t like. Our likes or dislikes of food can be based on taste – we simply don’t like it or we do. It can also be based on experience. If you didn’t like certain food as a child but you were forced to eat it, then as an adult, you may decide not to eat that food due to the negative experience. On the other hand, if you have an association with a positive experience you may crave that “comfort food” when you are having a bad day. Another example would be if you are stressed out or had a bad day and you don’t want to cook you navigate towards an easy solution to dinner and eat out at a restaurant or grab something at the drive-thru restaurant. If you experience stress over a long period of time and often cope with it by going out to a restaurant, that tends to use a large amount of fats and sodium then, in the long run, this will negatively impact your health.

Economic

Money plays a big role in eating habits and whether or not you can afford nutritious foods. Many parents struggle to buy “healthy” foods to feed their families. Sometimes it is cheaper to go to a fast food restaurant and purchase a full meal than it is to buy the ingredients. Not only is it financial economic it is also time economic. Sometimes work-life balance is off and you may not have time or energy to make dinner and multiple trips to the closest fast-food restaurant in a week.

Social, Religion and Culture

Food also has psychological, cultural, and religious significance, so your personal choices of food affect your mind, as well as your body. The social implications of food have a great deal to do with what people eat, as well as how and when. Special events in individual lives—from birthdays to funerals—are commemorated with equally special foods. Being aware of these forces can help people make healthier food choices—and still honour the traditions and ties they hold dear.

Typically, eating kosher food means a person is Jewish; eating fish on Fridays during Lent means a person is Catholic; fasting during the ninth month of the Islamic calendar means a person is Muslim. On New Year’s Day, the Japanese take part in an annual tradition of Mochitsuki also known as Mochi pounding in hopes of gaining good fortune over the coming year. Several hundred miles away in Hawai‘i, people eat poi made from pounded taro root with great significance in the Hawaiian culture, as it represents Hāloa, the ancestor of chiefs and Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians). National food traditions are carried to other countries when people immigrate.

Body Image and Media

How you see yourself in relation to the world affects your eating habits. If you are exposed to media that tells you that “skinny” is healthy, is beautiful and is the norm, then a person may adjust their eating habit in order to obtain that idea of “perfection”. In some cases, it can lead to eating disordered eating and eating disorders. With media all around us, it broadcasts what they deem as “normal” or “beautiful” to which we compare ourselves. In reality, those images are usually the minority. Media also tends to fail to acknowledge that there are many body types which are each unique and equally beautiful.

These are just a few factors that affect our eating habits. There are more and they are very complex, in that it may be one factor or it may be several intertwined.

Factors that Drive Food Choices

Along with these influences that affect eating habits, there are a number of other factors that affect the dietary choices individuals make, including:

- Taste, texture, and appearance. Individuals have a wide range of tastes which influence their food choices, leading some to dislike milk and others to hate raw vegetables. Some foods that are very healthy, such as tofu, may be unappealing at first to many people. However, creative cooks can adapt healthy foods to meet most people’s tastes.

- Economics. Access to fresh fruits and vegetables may be scant, particularly for those who live in economically disadvantaged or remote areas, where cheaper food options are limited to convenience stores and fast food.

- Early food experiences. People who were not exposed to different foods as children, or who were forced to swallow every last bite of overcooked vegetables, may make limited food choices as adults.

- Habits. It’s common to establish eating routines, which can work both for and against optimal health. Habitually grabbing a fast food sandwich for breakfast can seem convenient, but might not offer substantial nutrition. Yet getting in the habit of drinking an ample amount of water each day can yield multiple benefits.

- Culture. The culture in which one grows up affects how one sees food in daily life and on special occasions.

- Geography. Where a person lives influences food choices. For instance, people who live in Midwestern US states have less access to seafood than those living along the coasts.

- Advertising. The media greatly influences food choices by persuading consumers to eat certain foods.

- Social factors. Any school lunchroom observer can testify to the impact of peer pressure on eating habits, and this influence lasts through adulthood. People make food choices based on how they see others and want others to see them. For example, individuals who are surrounded by others who consume fast food are more likely to do the same.

- Health concerns. Some people have significant food allergies, to peanuts for example, and need to avoid those foods. Others may have developed health issues which require them to follow a low-salt diet. In addition, people who have never worried about their weight have a very different approach to eating than those who have long struggled with excess weight.

- Emotions. There is a wide range in how emotional issues affect eating habits. When faced with a great deal of stress, some people tend to overeat, while others find it hard to eat at all.

- Green food/Sustainability choices. Based on a growing understanding of diet as a public and personal issue, more and more people are starting to make food choices based on their environmental impact. Realizing that their food choices help shape the world, many individuals are opting for a vegetarian diet, or, if they do eat animal products, striving to find the most “cruelty-free” options possible. Purchasing local and organic food products and items grown through sustainable products also helps shrink the size of one’s dietary footprint.[16]

Pause to Reflect

|

Think of your last meal or snack. What are some of the factors listed above that led you to choose to eat what you did? |

Positive Eating Environments

Your role in promoting nutrition goes beyond, serving healthy foods. It includes creating a positive eating environment that supports the development of healthy eating habits. The key to a positive eating environment is to make it a priority. It is all about where, when, why and how you eat.

Alberta Health Services/Nutrition Service along with stakeholders in the child care sector (including ELCP directors, Educators, Cooks, Government, Post-secondary training programs, researchers and child care organizations) form a working group to discuss and share how to “raise healthy children”. Through their conversations and sharing they developed a range of resources including the concept of SET the Table for Success. SET is an acronym for Sit Together, Eat Together, Talk Together

Tips to support positive mealtimes

Checklist for supporting positive Mealtimes

Satter’s Division of Responsibility in Feeding: Caregiver’s responsibilities vs. Children’s responsibilities.

Ellyn Satter is a well-known dietician and an expert in feeding children. Satter has developed the Satter’s Division of Responsibility in Feeding. This model of feeding provides perspective to parents and caregivers that take the struggle out of meal times. It also teaches children to listen to their internal feelings that gauge their hunger.

| Satter's Division of Responsibility | |

|---|---|

| Caregivers are responsible for: | Children are responsible for: |

| What food is offered | How much to eat |

| When food is offered | Whether to eat - from what is offered |

| Where food is offered | |

The following PDF outlines the responsibility of the caregiver and child for each stage of feeding [17]. Note that as the child gets older the responsibilities shift.

Vegetarian Diet

People choose a vegetarian diet for various reasons, including religious doctrines, health concerns, ecological and animal welfare concerns, or simply because they dislike the taste of meat. There are different types of vegetarians, but a common theme is that vegetarians do not eat meat. Four common forms of vegetarianism are:

- Lacto-ovo vegetarian. This is the most common form. This type of vegetarian diet includes animal foods eggs and dairy products.

- Lacto-vegetarian. This type of vegetarian diet includes dairy products but not eggs.

- Ovo-vegetarian. This type of vegetarian diet includes eggs but not dairy products.

- Vegan. This type of vegetarian diet does not include dairy, eggs, or any type of animal product or animal by-product.[18]

Preparing vegetarian meals will be addressed further in Chapter 15.

Achieving a Healthy Diet

Achieving a healthy diet is a matter of balancing the quality and quantity of food that is eaten. There are five key factors that make up a healthful diet:

- A diet must be adequate, by providing sufficient amounts of each essential nutrient, as well as fibre and adequate calories.

- A balanced diet results when you do not consume one nutrient at the expense of another, but rather get appropriate amounts of all nutrients.

- Calorie control is necessary so that the amount of energy you get from the nutrients you consume equals the amount of energy you expend during your day’s activities.

- Moderation means not eating to the extremes, neither too much nor too little.

- Variety refers to consuming different foods from within each of the food groups on a regular basis.

A healthy diet is one that favours whole foods. As an alternative to modern processed foods, a healthy diet focuses on “real” fresh whole foods that have been sustaining people for generations. Whole foods supply the needed vitamins, minerals, protein, carbohydrates, fats, and fibre that are essential to good health. Commercially prepared and fast foods are often lacking nutrients and often contain inordinate amounts of sugar, salt, and saturated and trans fats, all of which are associated with the development of diseases such as atherosclerosis, heart disease, stroke, cancer, obesity, diabetes, and other illnesses. A balanced diet is a mix of food from different food categories (vegetables and fruits, grains, protein foods, and dairy).

Adequacy

An adequate diet is one that favours nutrient-dense foods. Nutrient-dense foods are defined as foods that contain many essential nutrients per calorie. Nutrient-dense foods are the opposite of “empty-calorie” foods, such as sugary carbonated beverages, which are also called “nutrient-poor.” Nutrient-dense foods include fruits and vegetables, lean meats, poultry, fish, low-fat dairy products, and whole grains. Choosing more nutrient-dense foods will facilitate weight loss, while simultaneously providing all necessary nutrients.

Balance

Balance the foods in your diet. Achieving balance in your diet entails not consuming one nutrient at the expense of another. For example, calcium is essential for healthy teeth and bones, but too much calcium will interfere with iron absorption. Most foods that are good sources of iron are poor sources of calcium, so in order to get the necessary amounts of calcium and iron from your diet, a proper balance between food choices is critical. Another example is that while sodium is an essential nutrient, excessive intake may contribute to congestive heart failure and chronic kidney disease in some people. Remember, everything must be consumed in the proper amounts.

Moderation

Eat in moderation. Moderation is crucial for optimal health and survival. Eating nutrient-poor foods each night for dinner will lead to health complications. But as part of an otherwise healthful diet and consumed only on a weekly basis, this should not significantly impact overall health. It’s important to remember that eating is, in part, about enjoyment and indulging with a spirit of moderation. This fits within a healthy diet.

Monitor food portions. For optimum weight maintenance, it is important to ensure that energy consumed from foods meets the energy expenditures required for body functions and activity. If not, the excess energy contributes to a gradual, steady accumulation of stored body fat and weight gain. In order to lose body fat, you need to ensure that more calories are burned than consumed. Likewise, in order to gain weight, calories must be eaten in excess of what is expended daily.

Variety

Variety involves eating different foods from all the food groups. Eating a varied diet helps to ensure that you consume and absorb adequate amounts of all essential nutrients required for health. One of the major drawbacks of a monotonous diet is the risk of consuming too much of some nutrients and not enough of others. Trying new foods can also be a source of pleasure—you never know what foods you might like until you try them.

Developing a healthful diet can be rewarding, but be mindful that all of the principles presented must be followed to derive maximal health benefits. For instance, introducing variety in your diet can still result in the consumption of too many high-calorie, nutrient-poor foods and inadequate nutrient intake if you do not also employ moderation and calorie control. Using all of these principles together will promote lasting health benefits.[19]

Pause to Reflect

|

Think back to your childhood, how do you think your diet did with regard to adequacy, balance, moderation, and variety? What about your diet now? |

Canada Food Guide

Creating a food-positive environment in early childhood settings plays an important role in establishing health-promoting and nutritional behaviours or habits. The Canadian Food Guide is a valuable resource that provides evidence-based recommendations on healthy eating. It offers guidance on food choices, serving sizes, and the proportion of different food groups to include in a balanced diet. By promoting a variety of nutritious foods and emphasizing the importance of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and lean proteins, the Canada Food Guide helps individuals make informed choices for themselves and their overall well-being. It also emphasizes the importance of the social-emotional aspect of eating (i.e. being with others, enjoying the foods you eat, relaxing) and brings to light the importance of having food skills (i.e. food literacy, shopping, cooking, creating). The goal of the Canada Food Guide is to support life-long healthy eating habits [20]

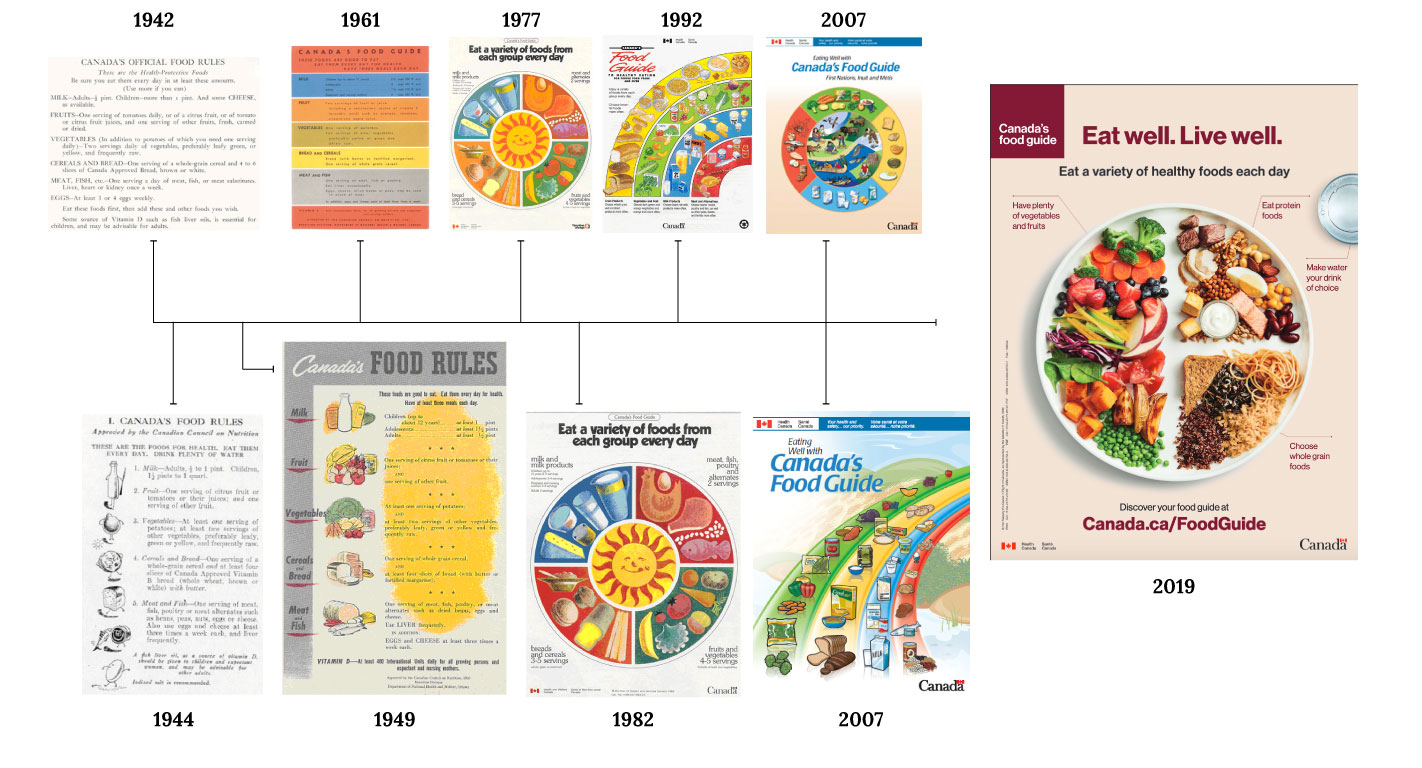

Brief History of Canad’s New Food Guide

There have been many variations of the food guide over several decades, as illustrated in Figure 1.2. The original food guide emerged in 1942; however, it was referred to as “food rules” at the time (Health Canada, 2019a). As you can imagine, the term “rule” is no longer used because it implies rigid principles with no recognition of social and cultural context. Prior to the 2019 version, the most recent adaptation to the food guide happened in 2007. That iteration included recommendations based on some studies and focused on four food groups: Vegetables and fruit; Grain products; Milk and alternatives; and Meat and alternatives. It also included the recommended number of servings in each food group and information about what is considered a serving for different types of food, based on gender and age.

In early 2019, Health Canada released a new food guide with accompanying documents such as “Canada’s Dietary Guidelines for Health Professionals and Policy Makers.” The aim of these resources is to support Canadians in patterns of healthy eating and nutritional well-being (Health Canada, 2019b). Alongside, it was time for a new food guide, especially since the last one was released over ten years ago. As a healthcare professional and/or a student in a health-related program, you are probably aware that guiding documents and resources should be informed by current evidence, which is typically considered five to ten years.

The new version of Canada’s Food Guide, hereafter referred to as Canada’s Food Guide 2019, has piqued great enthusiasm and interest because this version is based on evidence gathered from scientific reports, particularly systematic reviews, and wide-ranging consultation with health professionals, population and nutrition experts, national Indigenous organizations, and the general population (Health Canada, 2019b). The fact that this food guide is evidence-informed is significant because it aligns with the discourse of evidence-informed decision-making in healthcare and the abundance of health benefits and risks related to nutritional intake. Additionally, previous food guides were influenced by the food and beverage industry, which biased the recommendations.

Why Should You Care About the Canada Food Guide?

As an educator in early childhood education, you should be familiar with Canada’s Food Guide. In a world with changing food trends and fads, the Canada Food Guide provides easy-to-follow and trustworthy information based on research. The Canada Food Guide website (https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/) also provides a wealth of resources that will support you and help develop healthy nutrition policies. There are also many resources you can share with the families of the children you work with. Below is just a brief list of resources they have developed:

- The food guide snapshot

- Canada’s Dietary Guidelines for Health Professionals and Policy Makers

- Healthy eating recommendations

- Tips for healthy eating

- Recipes

As an educator, you have a role in modelling healthy eating habits for the children you work for and their families. There are many benefits of eating healthy for children in our care, they include:

- Helps children get the vitamins and minerals their bodies need.

- Helps children maintain energy throughout the day

- Helps brain development

- Helps develop strong teeth, bones and muscles

- Protects from diseases now and in the future.

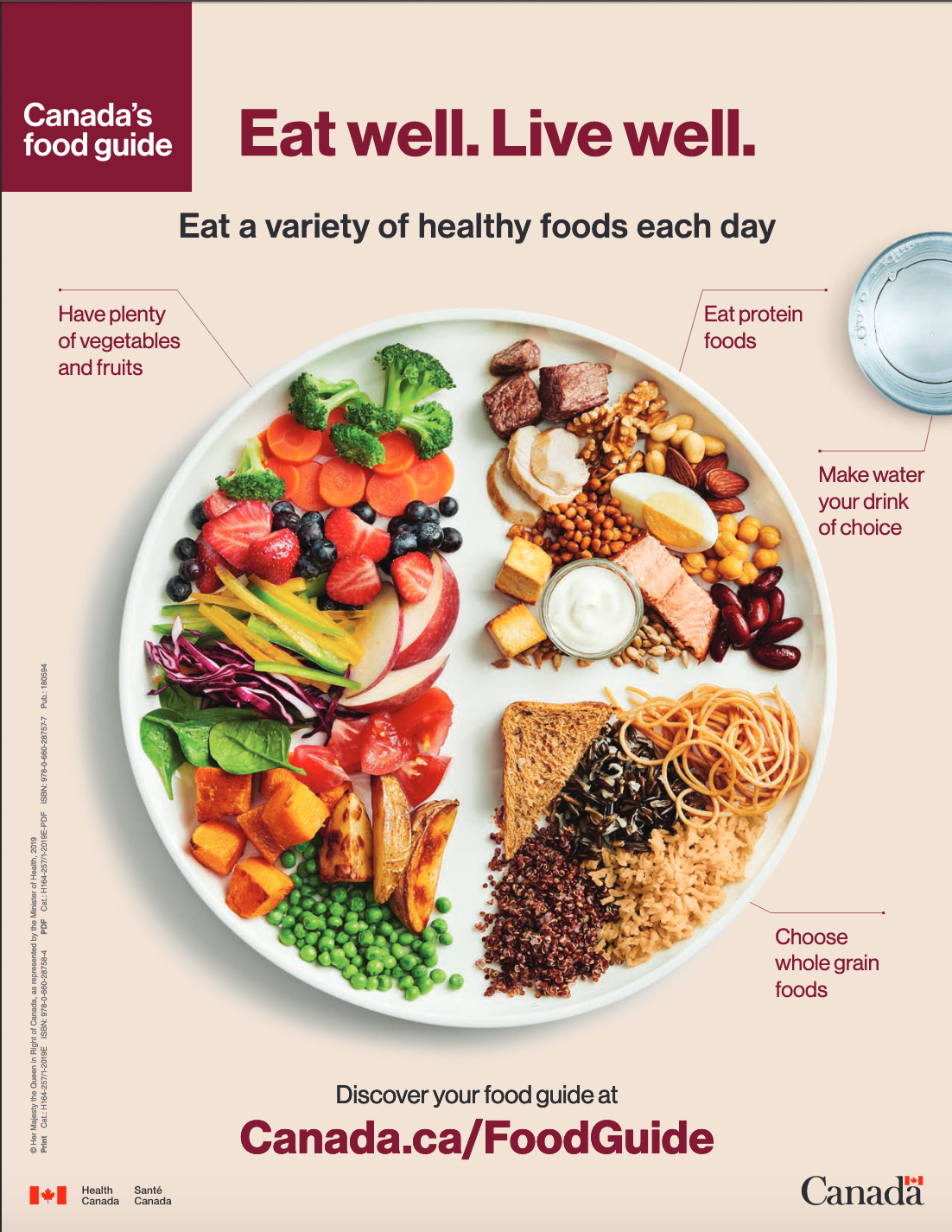

Canada’s Food Guidelines

Most Canadians see the image below (Figure 1.3) when they first attempt to access Canada’s Food Guide 2019 (Health Canada, 2019b). This image is part of the “Food guide snapshot” You can use this as a starting point for discussion with both children and their families.

When scanning the plate in Figure 1.3, you will notice a colourful plate with a diverse mix of foods in which: half the plate is filled with vegetables and fruit; one-quarter of the plate has proteins including tofu, legumes, nuts, seeds, yogurt, lean meat/fish and only a small amount of red meat; one-quarter of the plate has whole grain foods (e.g., bread, pasta, rice); and, there is a glass of water beside the plate.

Indigenous Food Guide

For more information on Indigenous food guide visit the First Nation Health Authority: Health Thought Wellness website or click on the images below.

See section 4: Promoting Healthy Eating in Children’s, Youth and Family Programs (pages 34-56).

See section 4: Promoting Healthy Eating in Children’s, Youth and Family Programs (pages 34-56).

Other Canada Food Guide Formats

The food guide snapshot is now available in 28 languages as illustrated in Figure 1.4.

Other relevant resources from the Canada Food Guide.

- Vegetarian recipes

- Healthy Snacks

- Healthy eating when pregnant and breastfeeding

- Kid-friendly recipes

The 3 Guidelines of Canada Food Guide

There are three specific guidelines that inform “Canada’s Dietary Guidelines for Health Professionals and Policy Makers” (Health Canada, 2019b).

As illustrated in Figure 1.5, the first guideline focuses on the integration of nutritious foods to form the foundation of a person’s eating patterns

Guideline 1: Foundation of Eating

Nutritious foods are the foundation for healthy eating. Vegetables, fruit, whole grains, and protein foods should be consumed regularly. Among protein foods, consume plant-based more often. Note: Protein foods include legumes, nuts, seeds, tofu, fortified soy beverages, fish, shellfish, eggs, poultry, lean red meat including wild game, lower fat milk, lower fat yogurts, lower fat kefir, and cheeses lower in fat and sodium. Foods that contain mostly unsaturated fat should replace foods that contain mostly saturated fat. Water should be the beverage of choice.

Considerations for Guideline 1:

Nutritious foods to encourage

-

- Nutritious foods to consume regularly can be fresh, frozen, canned, or dried.

Cultural preferences and food traditions

-

- Nutritious foods can reflect cultural preferences and food traditions.

- Eating with others can bring enjoyment to healthy eating and can foster connections between generations and cultures.

- Traditional food improves diet quality among Indigenous Peoples.

Energy balance

-

- Energy needs are individual and depend on a number of factors, including levels of physical activity.

- Some fad diets can be restrictive and pose nutritional risks.

Environmental impact

-

- Food choices can have an impact on the environment.

is a copy in part of the version available at: https://food-guide.canada.ca/static/assets/pdf/CDG-EN-2018.pdf

Guideline 2: Foods and beverages that undermine healthy eating

Processed or prepared foods and beverages that contribute to excess sodium, free sugars, or saturated fat undermine healthy eating and should not be consumed regularly.

Considerations for Guideline 2:

Sugary drinks, confectioneries and sugar substitutes

-

- Sugary drinks and confectioneries should not be consumed regularly.

- Sugar substitutes do not need to be consumed to reduce the intake of free sugars.

Publicly funded institutions

-

- Foods and beverages offered in publicly funded institutions should align with Canada’s Dietary Guidelines.

Alcohol

-

- There are health risks associated with alcohol consumption.

Guideline 3: Importance of Food Skills

Food skills are needed to navigate the complex food environment and support healthy eating

-

- Cooking and food preparation using nutritious foods should be promoted as a practical way to support healthy eating.

- Food labels should be promoted as a tool to help Canadians make informed food choices.

Considerations for Guideline 3

Food skills and food literacy

-

- Food skills are important life skills.

- Food literacy includes food skills and the broader environmental context.

- Cultural food practices should be celebrated.

- Food skills should be considered within the social, cultural, and historical context of Indigenous Peoples.

Food skills and opportunities to learn and share

-

- Food skills can be taught, learned, and shared in a variety of settings.

Food skills and food waste

-

- Food skills may help decrease household food waste.

Attribution Statements

Content related to the three guidelines, reflected in the three tables, was reproduced in part for non-commercial purposes, with editorial changes, from Health Canada (2019), “Canada’s Dietary Guidelines for Health Professionals and Policy Makers.”

Points of Consideration

As per Health Canada (2019b), Canada’s Food Guide 2019 was developed for individuals who are two years of age and older. In addition, it is noted that specialized guidance is required for those who are younger than two years of age and/or have specific dietary requirements such as protein, iron, and calcium intake among other nutrients. More information on infant feeding and healthy term infants up to 24 months can be located at: Infant Feeding and Healthy Term Infants.

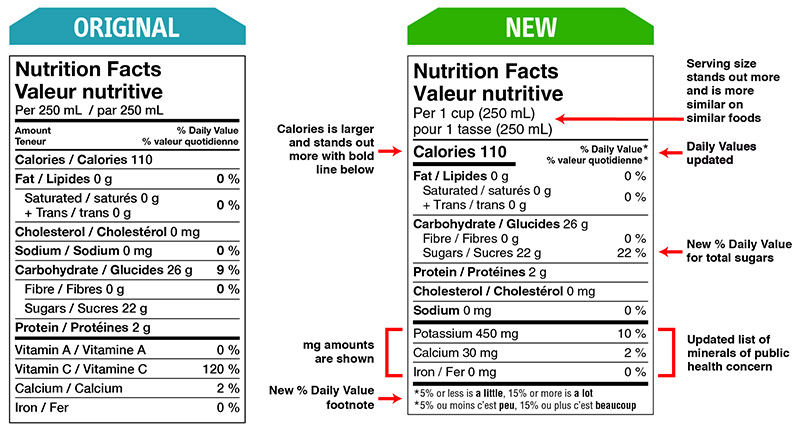

What is Nutrition Labelling?

Nutrition labelling is information included on labels of packaged foods about nutrient content. Considering the health impact of foods and the effects related to obesity, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and other conditions, there has been a shift in many countries to mandate and regulate nutrition labelling (Viola, Bianchi, Croce, & Ceretti, 2016). The Canadian government has made efforts to create labels that provide necessary information for consumers. However, it is important to be aware that nutrition labelling is often poorly understood by consumers. Health professionals are expected to be knowledgeable about how to read and interpret nutrition labels (including nutrition facts tables [NFT] and the ingredients list). Such knowledge will allow health professionals to help clients read nutrition labels, like that which is illustrated in Figure 12.16, and to make informed choices about healthy and safe eating that meets the dietary needs of each individual.

Health Canada is responsible for constructing policies to meet the standards set by the Food and Drugs Act (FDA). The Food Directorate of Health Canada is responsible for the “development of policies, regulations and standards that relate to the use of health claims on food” (Government of Canada, 2016, 3rd para). Other governing bodies, such as the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), have responsibilities for administering and enforcing food labelling policies as well as managing the Consumer Packaging and Labelling Act. Under this legislation, food producers must meet governmental labelling requirements.

Most prepackaged food labels (e.g., a can of soup, a bag of chips, a bag of frozen peas) must include the NFT, a list of ingredients, allergen statements, and best-before dates. The NFT is mandatory on prepackaged foods with the exception of some items such as alcoholic beverages and products that have few nutrients (e.g., coffee and spices). The Government of Canada (2019a) does not require nutritional labelling on foods such as fresh fruits and vegetables and foods sold at farmers’ markets. In general, it is mandatory to show both official languages of Canada (French and English) on labels, with some exceptions (e.g., specialty foods, local foods, test market foods, and shipping containers) as long as the products are not resold to consumers.

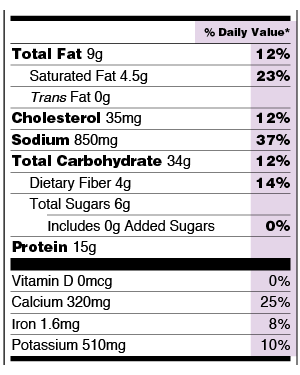

The Nutrition Facts Table and Ingredient List

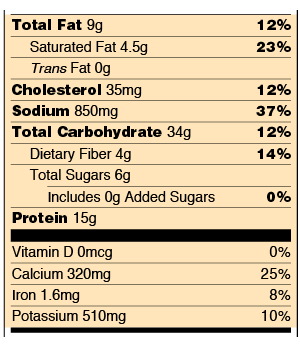

Under Government of Canada (2019a) regulations, the NFT must provide information about serving size, calories, percent daily value (%DV) of nutrients, and core nutrients. Currently, the requirements for nutrient information are changing and the industry has five years to make changes so that NFT include: fat, saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, sodium, carbohydrate, fibre, sugars, protein, potassium, calcium, and iron (Government of Canada, 2019a; Government of Canada, 2017). The figure below illustrates the new NFT as compared with the original (i.e., the previous version).

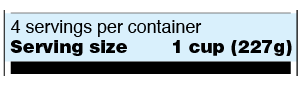

Serving Information

When looking at the Nutrition Facts label, first look at the top section at the number of servings in the package (servings per container) and the serving size. Serving sizes are standardized to make it easier to compare similar foods; they are provided in familiar units, such as cups or pieces, followed by the metric amount, e.g., the number of grams (g). The serving size reflects the amount that people typically eat or drink. It is not a recommendation of how much you should eat or drink.

It’s important to realize that all the nutrient amounts shown on the label, including the number of calories, refer to the size of the serving. Pay attention to the serving size, especially how many servings there are in the food package. For example, you might ask yourself if you are consuming ½ serving, 1 serving, or more.

Calories

Calories provide a measure of how much energy you get from a serving of this food.In the example, there are 280 calories in one serving of lasagna. What if you ate the entire package? Then, you would consume 4 servings or 1,120 calories.

Nutrients

It shows you some key nutrients that impact your health. Two key facts about the nutrients:

- Nutrients to get less of Saturated Fat, Sodium, and Added Sugars.

- Nutrients to get more of: Dietary Fiber, Vitamin D, Calcium, Iron, and Potassium.

The Percent Daily Value (%DV)

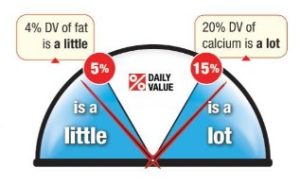

The % Daily Value (%DV) is the percentage of the Daily Value for each nutrient in a serving of the food. The Daily Values are reference amounts (expressed in grams, milligrams, or micrograms) of nutrients to consume or not to exceed each day.

The NFT displays the % DV so consumers can determine the amount of a certain nutrient in one serving. For example, the Government of Canada (2019b) indicates that 5% of the DV or less of a nutrient is considered “a little” while 15% of the DV or more of a nutrient is considered “a lot.” You should be aware that the % DV is not used to identify whether a person has had sufficient nutrients in a day, particularly considering that many foods do not require the NFT (Government of Canada, 2019b). Rather, it is a good way to compare and make choices between different types of food that are higher in healthy nutrients (e.g., fibre) and lower in nutrients that are not healthy (e.g., sodium and trans fat) (Government of Canada, 2019b).

Understanding Nutrition Labels

Time: 1:29

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Cq0wMtwsfk&t=6s

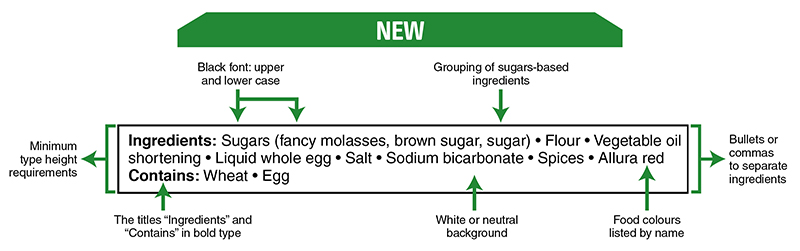

The list of ingredients (as illustrated in Figure 12.23) is mandatory on most packaged foods that contain more than one ingredient, and ingredients are listed in order of weight. In addition, caffeinated energy drinks require that the amount of caffeine is included with a statement that the product is a “high source of caffeine” and “not recommended for children, pregnant/breastfeeding women” (Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 2015).

Allergens

Where needed, food labels may also include an “Allergen Declarations and Gluten Sources” statement which captures the top ten priority food allergens. The ten priority allergens are set by Health Canada and include egg, soy, sesame seeds, milk, seafood, tree nuts (including peanuts as per Figure 12.24), sulphites, wheat, and mustard. If any of these priority food allergens are present, they must be listed in the ingredients and/or in a statement that begins with “contains” or “may contain” on a food product label.

It is prudent for any consumer, particularly people with food allergies or those who are purchasing or preparing food for people with allergies, to read food labels. It is important to note that companies can change ingredients without telling consumers; therefore, the responsibility to read labels remains with the consumer. When clients have an allergy, it is meaningful to discuss the importance of letting the host of a social gathering know ahead of time and always talking with the seller or producer of food at farmer’s markets and restaurants.

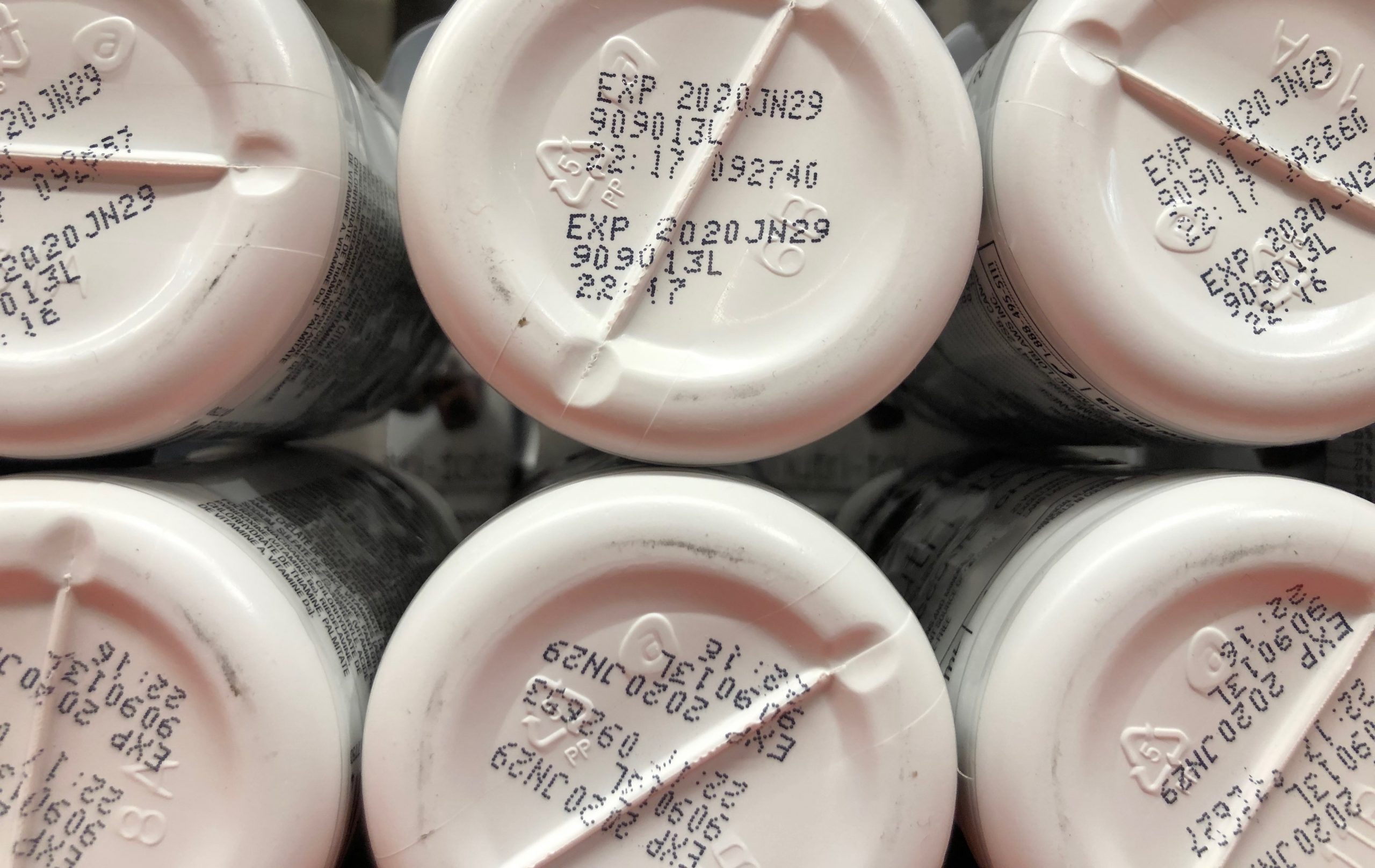

Best Before and Expiry Dates

The date (or meilleur avant) as illustrated in Figure 12.25 indicates the anticipated amount of time an unopened food product keeps its freshness, taste, nutritional value, or any other qualities claimed by the company when stored properly. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (2018) indicates that unopened products “should be of high quality until the specified date.” As soon as the product is opened, the best-before date no longer applies. The best-before date must appear on packaged foods that have a shelf life of 90 days or less such as milk, yogurt, and bread. Products still can be purchased or eaten after best-before dates as these dates are not related to product safety.

Expiration dates and best-before dates rely on a consumer’s ability to follow instructions concerning proper food storage. You may need to reinforce with clients the importance of keeping “cold food cold and hot food hot” so that bacteria do not grow (Government of Canada, 2014). The Government of Canada (2014) indicates that refrigerator temperatures should be kept at +4° Celsius and freezer temperatures are to be kept at -18° Celsius. Further information about refrigeration and freezer times for safety and quality can be viewed at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/general-food-safety-tips/safe-food-storage.html

Many of the food products sold and consumed in Canada are produced around the world, which is illustrated in Figure 12.27.

If a food product is imported from another country, its country of origin must be on the label. See Film Clip 12.2 of Dr. Lisa Seto Nielsen, a registered nurse, speaking about assumptions concerning food that is produced outside of Canada.

Video: Food Guide OER: Interview about assumptions concerning food that is produced outside of Canada.

Time: 0:53

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_QD9Lx1ouH0&t=19s

Transcript available with the host video – click ‘more’ in the description below the video and then ‘Transcript’

Film Clip 12.2: Dr. Lisa Seto Nielsen speaking about assumptions concerning food that is produced outside of Canada

If products are produced in Canada, they must include the name and address of the responsible company. Food products that say “Product of Canada” must follow specific guidelines. For example, a Product of Canada item must have most (generally 98%) of its food, processes, and labour originating in Canada. This means that “Product of Canada” foods were grown or raised by Canadian farmers and are prepared and packaged by Canadian food companies.

The claim “Made in Canada” means that the manufacturing or processing of the food occurred in Canada. A claim can be made on a label if the last substantial step in processing a product occurred in Canada, regardless of whether the ingredients are domestic or imported. For example, the processing of cheese, dough, sauce, and other ingredients to create a pizza would be considered a substantial step. If the food product contains some food grown by Canadian farmers, it can use the claim “Made in Canada” with domestic and imported ingredients. If all of the ingredients have been imported, it can use the claim “Made in Canada” from imported ingredients.

Pause to Reflect

|

Find a food that is marketed to young children (that has a food label). Looking at the label, how do you think it rates a healthy choice? Why? |

Regulations relating to Nutrition

Regulation for Nutrition for early learning centres and home daycares falls under the care of the Government of Saskatchewan: Ministry of Education. The Child Care Regulations, 2015 outline the Nutritional requirements for early childhood settings.

Section 24: Nutrition

(1) Subject to subsection (3), a licensee must provide meals and snacks for children attending the facility who are six months of age or older.

(2) A licensee must ensure that:

(a) subject to subsection (3), the meals and snacks provided meet the nutritional needs of the children attending the facility; and

(b) the manner in which children are fed is appropriate to their ages and levels of development.

(3) Subject to subsection (4), a licensee is not required to provide:

(a) infant formula or baby food; or

(b) meals and snacks for a child who requires a special diet or whose parent requests a special diet.

(4) A licensee of a teen student support centre or a teen student support family child care home must provide any foods, other than infant formula, required by an infant under the age of six months.

22 May 2015 cC-7.31 Reg 1 s24.

The Canada Food Guide is used as a guideline to determine if the menu has an adequate variety and amounts of food from the food groups for children over 2 years old. The CDC Licenee’s manual outlines the following :

- Snacks consist of two or more food groups including a serving of vegetables or fruit plus at least one other food group in designated amounts.

- Breakfast consists of three or more food groups in designated amounts.

- All other meals consist of four food groups in designated amounts.

- Offer milk at least twice a day.

- If you offer juice then:

- It is 100% unsweetened juice

- It is offered no more than 3 times per week

- Offer water for thirst.

- Foods to limit, if offered:

- Appear on the menu no more than a total of 3 times per week.

- Are in addition to the recommended food groups.

Summary

Providing nutritious meals and snacks to children in early care and education programs requires a basic understanding of nutrition. Program staff should also have an understanding of what a complete and healthy diet includes and how to address factors that influence food choices, to ensure that they provide healthy food and beverages that children will enjoy eating. Being aware of the programs available to support doing so is also valuable. Children who have high-quality meal and snack times will have the fuel their bodies need to sustain optimal growth and development

Resources for Further Exploration

· Nutrition.gov: https://www.nutrition.gov/

· Nutrition: https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/

· Definitions of Health Terms: Nutrition: https://medlineplus.gov/definitions/nutritiondefinitions.html

· Nutrition Education Resources & Materials: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/nutrition-education-resources-materials

· Consumer Information on Ingredients & Packaging: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging/consumer-information-ingredients-packaging

· Overview of Food Ingredients, Additives & Colors: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging/overview-food-ingredients-additives-colors

· Preventing Childhood Obesity in Early Care and Education Programs: https://nrckids.org/CFOC/Childhood_Obesity

· ChooseMyPlate: https://www.myplate.gov/

· Child and Adult Care Food Program: https://www.fns.usda.gov/cacfp/child-and-adult-care-food-program

· CACFP Regulations: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-04-25/pdf/2016-09412.pdf

· Nutrition Standards for CACFP Meals and Snacks: https://www.fns.usda.gov/cacfp/meals-and-snacks

· Food and Nutrition Service Programs: https://www.fns.usda.gov/programs

· Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020: https://health.gov/our-work/food-nutrition/2015-2020-dietary-guidelines

· Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans: https://www.hhs.gov/fitness/be-active/physical-activity-guidelines-for-americans/index.html

· Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care: https://gonapsacc.org/self-assessment-materials

References

- Image by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Salt Shaker on White Background by Dubravko Sorić is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Image by Suzy Hazelwood on Pexels ↵

- Food Coloring Bottles by Larry Jacobson is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Government of Canada: Health Canada-Food additives (2023) ↵

- Government of Canada: Health Canada-Food additives (2023) ↵

- Government of Canada – Canadian Food Inspection Agency (2023) retrieved November 19, 2023 https://inspection.canada.ca/food-labels/labelling/industry/food-additives/eng/1623872657859/1623873217667#c1 ↵

- No-Calorie Sweetener Packets by Evan Amos is in the public domain ↵

- Artificial Sweeteners and Cancer by the National Cancer Institute is in the public domain ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- From "Raise a healthy child who is a joy to feed", by Ellyn Satter, From the Ellyn Satter Institue copyright 2023, used with permission ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Resouces for health professionals and policy maker, Government of Canada, is used with permission ↵

- Canada's Dietary Guidelines for Health Professional and Policy Makers, Government of Canada, in the public domain ↵

- Healthy Food Guidelines: For First Nations Communities, First Nations Health Authority ↵

- First Nations Traditional Foods: Fact Sheets, First Nations Health Authority ↵

- Food Guide Snapshot: available in 28 languages, Government of Canada, in the public domain ↵

- Image by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration is in the public domain ↵

- Image by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration is in the public domain ↵

- Image by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration is in the public domain ↵

- Image by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration is in the public domain ↵

- Image by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration is in the public domain ↵