1.4 The History of Disinformation

This section explores three examples of disinformation throughout history. They come from different cultures and different time periods. Each historical example is followed by a more contemporary event or story to show that although it might look, sound, and smell different in today’s world, it is much the same.

The First Roman Emperor

In 44 BC, the famous Roman General Julius Caesar was assassinated. In this year, his nephew Octavian (who would later become known as Augustus) began a lengthy disinformation (defamation) campaign to eliminate his rivals and come to power. First, he needed to defeat his political opponent Marc Antony. He used a disinformation campaign to convince the Roman people that Marc Antony did not represent Roman values. Most of the disinformation campaign focused on Marc Antony’s love affair with the African Queen Cleopatra–who was viewed by the Roman population as a foreigner who could not be trusted. In songs, poetry, and short lines on coins (which people have referred to as ancient tweets) Marc Antony is referred to as a degenerate–which, in politics throughout history, suggests that a person’s physical or mental health is declining (Hughes, 2013). Degeneration also calls into question an individual’s morality – their ability to understand the difference between right and wrong. Augustus ultimately defeated Marc Antony in battle. Even after Marc Antony’s death, and after Augustus became the first emperor of Rome, the campaign continued. Augustus dedicated decades to glorifying his image with stories, monuments, statues and coins. He portrayed himself as Augustus the Statesman, Augustus the Peace Bringer and Augustus the Commander (Kaminska, 2017; Pollock, 2017). These images have outlived the emperor and they have become a propaganda roadmap for politicians throughout modern history.

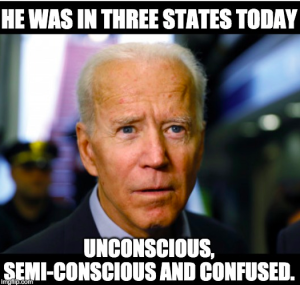

The practice of calling a political rival’s health into question is still used today. For instance, the health status of the current President of the US, Joseph Biden, is often remarked upon in the media. He has been nicknamed “sleepy Joe” by his rivals and his family is often tasked with defending his advanced age in interviews (Kalter, 2020; Mangan & Wilkie, 2021; Smith, 2022). Even though his doctors have said he is in good health and the summary report for his medical examination is available, his mental capacity and his physical health is still questioned (Mangan & Wilkie, 2021).

The meme below gives an example of a propaganda-like attack on Biden’s health. It is easy to share over the Internet and its comedic nature may appeal to many groups of people. Some experts have claimed that memes are the new propaganda. A look at the meme of Biden below might prove that exact point. Augustus reigned over approximately one million people in the city of Rome-not including the entire Roman Empire (Storey, 1997). How long would it take for the Biden meme to reach one million people today? Imagine how much quicker Augustus could have taken Marc Antony down if he’d had access to the world wide web, graphic design tools and a constant 24/7 audience. It probably wouldn’t have taken fourteen years, which is the amount of time between the deaths of Julius Caesar and Marc Antony (the length of the defamation campaign).

The Great Moon Hoax

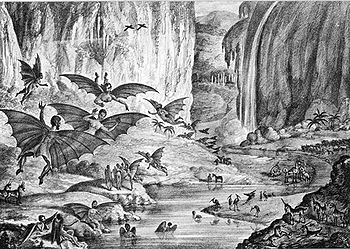

In 1835, the New York Sun, a relatively new newspaper, created a hoax to poke fun at a science writer who had made claims that the moon had billions of inhabitants. The suspected author of the articles claimed to be a scientist who was friends with a famous astronomer, Sir John Herschel. The article claimed that Herschel, using a telescope, had seen life on the moon, including humans with bat-like wings, bison, goats and tail-less beavers. The series of six articles included illustrations of the civilization (see Figure 9) which were widely believed. The newspaper’s sales shot up and a committee of Yale scientists began to search for the original observations published by Herschel. When asked about the telescope through which the amazing images had been viewed, the paper claimed that it had been destroyed in an unfortunate melting accident caused by the sun. In September of the same year, the newspaper acknowledged that the entire thing had been a hoax, which is the creation of misleading information, which intends to make someone believe something outrageous. The paper continued to do well until 1950, and most people who read it were said to have been amused by it (History.com, 2020).

Now for a modern-day hoax, in 1995, Fox broadcast Alien Autopsy: Fact or Fiction. The creator of the show presented it as authentic footage of an alien autopsy in Roswell, New Mexico. However, the director along with other experts who had consulted on the film tried to alert Fox that the film seemed to be fake, calling the featured footage a hoax. But Fox did not want that information to get out before the broadcast, as they knew that if the public believed they were viewing an actual alien autopsy, their ratings would skyrocket (Wikipedia, 2022). Sure enough, each time the show aired, it had higher and higher ratings. Finally, in 2006, the filmmaker admitted that the footage was not authentic, but he maintained that there was actual video footage of an alien autopsy that was too degraded to be used in the 1995 film (Wikipedia, 2022). Could this be considered a modern-day example of hyping up a false story to increase ratings and profits?

Influenza Pandemic Disinformation Campaign

Throughout 1918, a pandemic of the influenza virus killed an estimated 20 to 40 million people worldwide. It is famously known as the Spanish flu, even though its origin has been traced to a US Army camp in Kansas (Davis, 2018). The illness spread during World War I. Some speculate the reason it is known as the Spanish flu is because Spain, a neutral country, meaning they didn’t take a side, didn’t hide the number of infections happening daily in that country. They openly published their numbers which made them appear to have more infections than other countries who were purposefully misinforming the public (Davis, 2018).

But why would a country suppress their infection numbers? The countries that were actively fighting in the war wanted their populations to focus on war efforts, not on the flu, so they claimed that the virus was under control and even refused to publish letters of warnings from the medical community (Davis, 2018). People living in Philadelphia would become the victims of the US’s disinformation campaigns. In March of 1918 the city hosted a Liberty Loan March to raise funds for the war effort. Editors at a newspaper refused to run doctors’ letters warning people not to participate in the event to avoid spreading and contracting the flu. Additionally, the medical community was unable to convince the city’s public health director to tell people not to attend. Over the coming weeks more than 12,000 Philadelphians died from infection. The March has widely been considered the super spreader event that catalyzed the enormous number of infections and deaths (Davis, 2018; The Week Staff, 2020; Flynn, 2020).

Dishonesty and manipulation can have an impact on health issues today, as well. In recent years, evidence is appearing to indicate that Big Pharma companies led disinformation campaigns pertaining to opioids. Purdue Pharma has been found to have made misleading claims about Oxycontin calling it a weak opioid that is safe for chronic pain. They have been accused of claiming that use of the drug would not result in addiction (Bavli, 2019). To add to this, they had used an aggressive marketing strategy to get more people to use Oxycontin. Between January 2016 and September 2018 there were 10,300 opioid-related deaths in Canada (Bavli, 2019). In 2018, a group of physicians and opioid experts asked for an investigation into Purdue Pharma’s claims, feeling that as a medical community, they had been misinformed and manipulated in ways that led them to over-prescribe the drugs to their patients (Bavli, 2019). In 2020, the company pled guilty to felony offenses including fraud, they are now facing a multi-billion dollar fine (Department of Justice, 2020).

A hoax is created using misleading information, with the intention to deceive someone into believing something that can be outrageous or absurd.