3.5 Google and Facebook are Big, But False Information is Bigger

In 2021, US President Joe Biden chastised social media companies for their lack of action against the spread of false information. Speaking about the COVID-19 pandemic, Biden said that social media platforms were “killing people” (Reuters, 2021, para. 1). When he said this, he was referring to the fact that (at that time) most people who were dying from COVID-19 in the US were unvaccinated. He claimed that vaccine disinformation was to blame and that social media platforms should be doing more–Biden pointed his finger specifically at Google, YouTube and Facebook (Reuters, 2021). In doing research for this book, we ourselves have thought along these lines. The companies who run search engines and social media platforms are aware of disinformation and fake news, filter bubbles, and information overload. They are very wealthy and they have resources, so why don’t they just fix everything? Unfortunately, as with everything we’ve discussed so far, it’s not that simple.

The next section will examine efforts taken by large tech companies, specifically Google, Meta and Twitter to combat false information on their platforms. It is important to note this section is a reflection of the time period within which we conducted research and wrote the book. The systems described have continued to evolve and it is likely that many of them will have changed by the time it is read. Case in point, mere weeks before publication, Elon Musk acquired Twitter. Immediately following this acquisition, he dubbed himself a “free speech absolutist,” reinstating accounts that had previously been banned for posting content that had violated Twitter’s policies (Lee, 2022, para. 1). Under Musk’s leadership, several thousands of employees have lost their positions, making it even more difficult for the company to maintain its standards (Lee, 2022). To add to this, Musk introduced a profit generating system which enables anyone to purchase a verified account (Schreiber, 2022). All of these changes will result in major interruptions to Twitter’s ability to uphold reliable information. A stunning thing occurred the day after Musk took over the platform, the use of the ‘N’ word went up more than 500 times and in the week following, anti-vax and pseudo science accounts purchased verified profiles making them look like legitimate sources of health information (Murphy, 2022). As you read the next section, consider that everything described is in a constant state of flux and change. It will provide a base understanding for the tools that can be used by social media companies and how they might be effective; however, they could be modified or disappear at any given time.

3.5.1 Attempts to Fix the Problem

Google. Google LLC says “it is one thing to be wrong about an issue. It is another to purposefully disseminate information one knows to be inaccurate with the hope people believe it to be true or to create discord in society” (Google, 2019b, p. 2). The company highlights four initiatives they’re taking to fight disinformation. First, they point out their ranking algorithm and the fact that it is designed to ensure that users find useful resources that do not support specific viewpoints (Google, 2019b). They claim that their search engine stops spam and any bots or individuals who try to manipulate their algorithm to be placed higher in search results (Google, 2019b). Remember the pizza search from a previous section, Google’s algorithm is designed to find and remove clickbait sites from the index. Second, Google has policies against misrepresentation. For example, a news site that claims to report from Ireland, but whose activity is coming from Canada is misrepresenting their location, the algorithm is designed to flag these instances and eliminate them from search results. The third aspect relates to the amount of information made available: A LOT. They claim that by providing more coverage in a variety of ways, they are helping searchers to evaluate information (Google, 2019b). Lastly, Google claims to support journalism and fact checkers. Google financially supports organizations who have the goal of fighting disinformation (Google, 2019b).

Social Media. Social media platforms have also dedicated resources to services and policies to stop the spread of false information. TikTok’s (2020) owners state that they are very aware of the dangers of their recommendation algorithm, citing specifically the potential for people to end up in unintentional filter bubbles. They have a Transparency Center that works to battle the potential harms of users viewing biased information. They invite experts to view and understand their algorithm and they have designed aspects of the algorithm to populate diverse content. Occasionally, a user may see a video that is unlike their regular preferences. TikTok (2020) cites this as a purposeful part of the calculation. They also point to users’ ability to hide, mark “not interested,” or report content and creators of unappealing and even troublesome content.

3.5.2 Policies

In addition to adjusting algorithms, many social media companies have been changing their policies to address the spread of disinformation. We will look at Facebook and Twitter. In Facebook’s (n.d.) Taking Action Against Misinformation, they claim to remove content that violates their Community Standards, reduce misinformation, and provide people with context so that they can decide what to read, trust, and share. They state that they reduce misinformation by using fact-checkers and labels to identify posts that violate their Community Standards.

Twitter has adopted similar strategies. In COVID-19 Misleading Information Policy, Twitter (n.d.) claims to label or remove false information about the virus, treatments, regulations, restrictions, or exemptions to health advisories. They also limit the ‘reach’ of content if it is posted by users who have repeatedly posted false information (Twitter, n.d.). Accounts that violate the policy go through a ‘strike process’ that follows these steps: tweet deletion, labeling, and finally, account lock and permission suspension. In their policy, Twitter (n.d.) specifically states that they recognize their platform is used by people to debate, express strong opinions, and post about personal experiences, which indicates that they are mindful not to censor content too severely.

Reporting

An early feature adopted by many social media platforms is the ‘report’ button that indicates a user believes a post is in violation of that site’s policies, or frankly and more likely, posts that the individual finds personally offensive or problematic (Khan & Idris, 2019). This is an example of community-driven evaluation. Reporting a post flags it so that it will go under review by someone working for the company. It is an important act of digital citizenship to report posts that are known to be misinformation, disinformation, malinformation or propaganda to slow their spread (Stecula, 2021). However, there is a fine line between reporting posts that are outright false information and reporting them because they include content an individual does not agree with.

Barriers and Two-Factor Authentication

Barriers are another social media feature designed to verify that the person interacting with a website is a real person, not a bot. CAPTCHA is a commonly known example of this. Before allowing a user to sign-in, complete a purchase or add comments, it asks users to engage in an activity a computer cannot complete, often to select pictures of a particular item within a larger frame (for example, select all the sections that have boats) (Menczer & Hills, 2020). Two-factor authentication is another example of a barrier where the system verifies a user’s identity by asking specific questions or sending a personalized code to a second, known device, which can then be entered for login. Why is this necessary? For a multitude of reasons, but one that relates to our examination is the fact that bots have the ability to guess passwords. Because they are robots, they can continually try different options until they succeed. Requiring multiple pieces of information places more barriers in front of the bots and provides more security for users and platforms (Klosowski, 2022).

3.5.3 Labeling

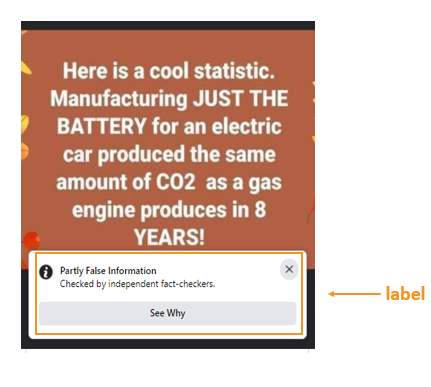

The use of labels on posts is a recent and constantly changing adoption by social media companies. Labels are used by each company in a slightly different manner (Stecula, 2021). Facebook is one of the first social media platforms that incorporated labeling. When a person attempts to engage with a post, their action is paused, and the label appears. The first labels placed on posts said that the claims in the post had been disputed by fact-checkers (Silverman, 2017; Pennycook et al., 2018). Over time, the company took it a step further by adding links to authoritative information (which users could choose to click on). At the time of writing, Facebook is using a warning system, which places a veil over the false content (so the user cannot see it or share it), as well as a misinformation warning (Grady et al., 2021). To view the content, a user must click past the warning. It is very interesting to note that some of these labels are applied to posts by an algorithm or bot, not a human fact-checker (Facebook, n.d.).

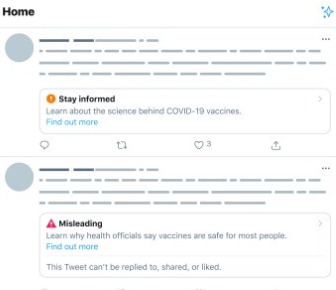

In 2020, Twitter began using labels. Their labels shade the text on a tweet and require followers to click through to see content, much like the label system currently being used by Facebook (Bond, 2020). In addition to this measure, users cannot share a labeled tweet without commenting on it. The requirement for people to engage, rather than just click, is an effort to slow the spread of disinformation because it not only requires people to be thoughtful about their actions but it also limits the ability of bots to re-tweet false information (Bond, 2020). Since Twitter adjusted its labeling system in July 2021, their new labels say either “Stay informed” or “Misleading” and appear prominently below tweets of concern (Twitter Support, 2021). Additionally and importantly, once a tweet has been labeled, it no longer appears to users through the recommendation algorithm (Bond, 2020).

Spotify, too, has recently started labeling some podcasts. So far, these labels are only used on podcasts that specifically have misinformation about COVID-19 (Zukerman, 2022). If a user is listening to a podcast about COVID-19, they are prompted by a label containing a button that leads to more information about the virus.

While labels may seem to be a good intervention to limit the spread of misinformation, they do highlight other problems related to sharing information on social media platforms. One concern is that people will become familiar with labels on false information and begin to assume that any unlabelled post is trustworthy. This is worrisome because, due to the sheer amount of information shared online, there will always be a huge amount of unlabelled posts (Dizikes, 2020). There is also trepidation that accurate but controversial posts may be labeled, transforming the practice into a tool for censoring by big tech companies, i.e., Facebook could potentially label information that they deem inaccurate or unfavourable (Menczer & Hills, 2020). As we have seen above, companies are trying to balance free speech with decreasing the spread of misinformation by shading posts, but will that continue to be the case? Finally, there is the overarching debate over whether we can trust those that are assigning the labels (Menczer & Hills, 2020). Similar to the concerns related to coders bringing their personal biases into the creation of algorithms, tech companies selecting what is flagged is in itself a problematic system.

Facebook, Twitter, and Spotify have used labels in different ways. Why does their approach keep changing? As we learn more about how disinformation affects human psychology, labels are changed to align with findings. In the next chapter we will discuss something called the Illusory Truth Effect, which postulates that the more individuals see information the more likely they are to believe it. The use of labels is an attempt to limit the amount of disinformation we see in the first place (Pennycook et al., 2018; Buchanan, 2020b). One study found that if participants had seen false information in multiple locations, even though they knew it to be false, many still considered it acceptable to share that information because they had seen it multiple times (Buchanan, 2020b). However, another study found that labels increase a user’s skepticism, providing a chance to pause and consider before sharing information (Pennycook et al., 2018).

3.5.4 Moderators and Fact-checkers

Moderators and fact-checkers are the human element deployed by several social media companies in their continual effort to combat disinformation. These individuals are tasked with evaluating posts that have been reported and verifying the information with trusted sources. Some fact-checkers are called third parties which means they don’t work for the company and are more likely to be neutral. These individuals are often certified in evaluating information and focused on finding the most accurate answer. Facebook and Instagram employ independent fact-checkers to label some posts. Facebook will remove content that has false claims about COVID-19 (Facebook, n.d.) while Instagram removes the ‘explore’ option and searchable hashtags on the post to limit spread (Stecula, 2021).

Twitter uses a community-driven method called birdwatch that is similar to Wikipedia’s verification method (Dizikes, 2020). Random users are assigned to review tweets reported to be false information and they volunteer to add notes about why the tweet is incorrect. Twitter claims that a “community driven approach to addressing misleading information can help people be better informed” (Coleman, 2021, para.1). However, one must ask, when does birdwatching turn into censorship? Censorship is suppressing words, images or ideas that are considered problematic by those doing the censoring, and since there is a human component to fact-checking, it will always lead to the question: what right does a person have in deciding if information presented to a user is good or bad? Also, how many people are willing to participate in unpaid work? Definitely not enough to solve the ever-growing problem.

As we have seen, and it is especially the case with Twitter, false information is created and spread quickly by bots. Fact-checking systems, especially those that utilize real live human beings, cannot keep up with the large amount of false information created each day (Dizikes, 2020; Stecula, 2021). Some social media companies have tried to develop AI moderators to assist with the review of posts with low success. A review of Facebook’s moderating system found that 300,000 mistakes were made a day as it tried to work through all the content reported (Stecula, 2021). A study that looked at several social media platforms found that 95% of the content that was reported to be problematic was never reviewed (Jarry, 2021). If the largest and most profitable tech companies in the world cannot keep up with the amount of false information posted and shared each day, how can the average user be expected to identify it?

3.5.5 Removing Content and Users

Some social media platforms have removed problematic content or suspended users’ accounts. For example, both Facebook and YouTube remove content that specifically aims to misinform people (Grady et al., 2021). Facebook published a report that outlines the disinformation campaigns that they have removed from their platform (Fisher, 2021). Removing content does reduce spread but the content often moves to another platform on the Internet (Grady et al., 2021; Zukerman, 2022). This practice comes with some concerns because the line between censorship and stopping misinformation is unclear (Zukerman, 2022).

As we have seen, the large companies online are attempting to combat disinformation. They are being called upon by world leaders and populations to fix the problem but, as we’ve also seen, the problem is very complex. Those creating disinformation range from small operations to well-funded websites supported by powerful people. Sometimes disinformation is spread by those with good intentions, unaware that they are even doing it. Social media and search engine companies can put endless amounts of resources and money into this problem, but they are still unlikely to catch up with it, so it ultimately comes down to users who must be aware and always consider the purpose and agenda of the information source. In the next chapter, we will see how human interaction with online systems lends to the spread of false information.