4.2 Social Media and Disinformation

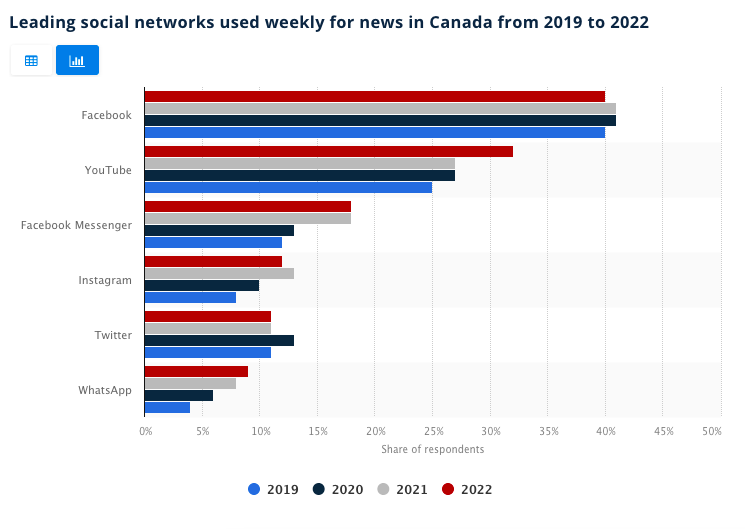

Social media has impacted how people share and consume news. A 2018 survey of Americans showed that 50% of Internet users hear about news on social media before hearing it through a traditional news outlet (Martin, 2018). This trend hasn’t changed much, a 2020 survey indicated that 48% of US adults say they get their news from social media often or sometimes (Walker & Matsa, 2021). From 2019 to 2021, 21% of Canadians surveyed, stated that they get their weekly news from social media, with Facebook in the lead (41%), followed by YouTube (32%) (Watson, 2022; see figure 20). As we saw in chapter two, throughout the pandemic as the issue of disinformation worsened in relation to healthcare and vaccine-related topics, people’s use of traditional news outlets went up. However, it is very likely that many individuals were still accessing these news sites via social media, and they probably continue to do so. Newsfeeds run by and on social media platforms have become the place where many people access information about current events.

The trend of seeking out news on social media platforms is especially popular among younger generations, some of whom admit that they like to learn about important issues from famous individuals, such as activists, on social media. Activists are individuals who support one side of an issue strongly and are often well-known for participating in protests (Merriam-Webster, n.d.e). Greta Thunberg is an example of a young environmentalist who has become popular for her activism; many people of younger generations follow her for information about climate change (Walker & Matsa, 2021; Wikipedia, 2022). Meanwhile, those who are relying on online personalities (activists, celebrities, influencers) for their information often do not effectively evaluate the information they find online. One survey found that more than half of college-aged students examined do not verify the truthfulness of the articles they read and that those who do might consider things like appealing web design to be the deciding factor of good versus bad content (Chen et al., 2015). Considering the Greta Thunberg example: at what point does gathering information from an activist become problematic? What makes an activist an authoritative figure? When does an activist become an influencer and why should that concern social media users?

4.2.1 Social Media Makes People More Susceptible

Disinformation has been a problem throughout known history. But in the Internet age, the problem has worsened. Why? In large part, it can be attributed to the social media environment. Throughout our research, we have come to find that four main reasons are cited for people’s belief in false information online and each of these reasons encompasses other social media trends that are worth discussing. It all begins when an individual views a post on their social media feed–it might be a sponsored post (placed there by social media advertisers and algorithms), something shared by a friend, or something shared by a page they like. After the person sees the post, the following four things might impact their reaction to it:

- the post appears to be credible,

- the post stirs emotion,

- the post is something that the individual has seen repeatedly,

- the post is something the individual already believes to be true.

The post appears to be credible

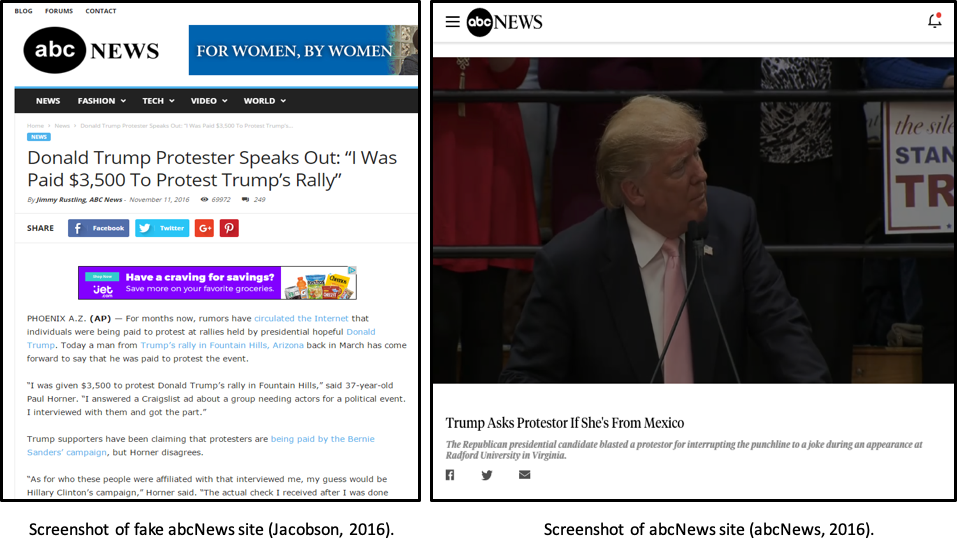

One only needs an idea and access to a device to create content that looks official. With the various information technology tools available, such as graphic design tools, website builders, access to photography, video creation and editing tools, many are able to create professional-looking websites and social media posts (Horner et al., 2022). This environment has caused new and troubling trends to emerge, among them mimicking. This is a technique where a false news site will mimic the design of a reputable news source (Stecula, 2021). The false news source will have a url that is similar to a reputable news source, but when examined closely the About Us section will be sparse (lacking any journalistic or editorial standards, or faking them), and the stories will be sketchy and biased (Molina et al., 2019). Most of these sites are created to generate ad revenue quickly (Molina et al., 2019). However, when these stories are detached from the website and shared on social media, they can appear credible (Stecula, 2021). In this way, technology can become a powerful enabler of disinformation. The example below shows two different websites with the abcNews logo at the top; can you tell which one is the authentic news site and which is the mimicked site?

Another concerning trend that can be credited to advanced technology is the creation of deep fakes. These are videos that appear to show well-known people doing things that did not actually happen (Dickson, 2020). Technology has made it possible to take the face of one person and transpose it onto the face of another. It is also possible to create sound that mimics a specific individual’s voice (Dickson, 2020). A common example of a deep fake is nonconsensual pornography where a celebrity’s image is imposed on the actual person appearing in the film (Dickson, 2020). Other deep fakes show politicians doing and saying things that are out of character. These videos spread quickly on social media and are difficult to detect. It is important to seek other sources to verify the content of videos that seem a little weird or unrealistic.

Technology also deserves credit for how quickly information spreads. Face to face interactions spread information slowly and while paper can spread it quite quickly, publishing in print is expensive and time-consuming (Horner et al., 2021). Social media allows information to be shared immediately with a much larger group at a low cost.

The post stirs emotion.

On social media, knowing that information has been proven false doesn’t dissuade people from engaging with it, rather it tends to make it more appealing and shared more widely. Those responsible for the creation of disinformation online understand that causing viewers to be emotional will fulfill their goal of getting more engagement. Engagement is “the number of reactions, comments, shares and clicks on a post” (Meta, n.d.). Most posts, especially news stories, insight an emotional reaction in people, it might be excitement and joy, annoyance and anger, and everything in between. People might even experience a feeling of vindication (“I knew I was right!”). Or after reading a post that they know to be untrue, they might want to make a comment to ensure their friends know the information is wrong.

In the past decade, numerous psychologists have studied the emotional responses of social media users. They have found that in the current environment of information overload, our brains have learned to prioritize information that triggers a high level of emotion, while glossing over unexciting information that doesn’t cause a reaction (Barr, 2019). When people have an emotional reaction to something they read, they are more likely to engage with it – by liking, commenting, or sharing (Horner et al., 2021). The more upsetting a post is, the more viral it will become (Barr, 2019). When a person is feeling especially emotional, they are more likely to believe what they read (Pennycook et al., 2019). During times of political disagreement or public fear, posts that stir emotion multiply and circulate at an exponential rate.

The amount and pace of conflicting views circulating around the Internet is leading to a circumstance which challenges people to examine their reactions and fact check before sharing. Pennycook et al. (2019) recommend using Google to search for the headline that has stirred emotion because it is often the case with false news headlines that by the time an individual sees it, it has already been debunked by someone else. By doing a quick search, the user may stop themselves from sharing disinformation and save themselves the emotional energy they might have otherwise wasted on a false headline. Most Google searches take less than one second to complete, is that a reasonable amount of time to invest in ensuring something is true?

The post is something that the individual has seen repeatedly

The more a person is exposed to a particular piece of information, the more likely they are to believe in it (Dwyer, 2019; Buchanan, 2020a; Hassan & Barber, 2021; Stecula, 2021). As discussed in the previous chapter, social media algorithms select what stories to show users based on popularity, meaning the more people that have commented on or liked a post, the more likely other people are to see it. Some experts state that dangerous repetition or the illusory truth effect explains why advertisements, disinformation, and propaganda are so impactful (Buchanan, 2020a; Hassan & Barber, 2021). Many scientific studies have confirmed that repetition will increase the belief in and circulation of rumours, false news and disinformation, whether or not the information has been openly debunked and no matter when the repetition occurred (within a day, a week, or a year) (Hassan & Barber, 2021).

Those who want to spread disinformation understand these algorithms and use bots and trolls to boost the popularity of specific content. These manipulative technologies or individuals (in the case of trolls) work to make sure that social media users see a piece of disinformation multiple times. They know that the more it is repeated, the more influence it will have. Once people process information, it is very difficult to remove its influence from their mindset (Dwyer, 2019). To add to this, the more familiar a person becomes with a concept, the more justified they believe they are in spreading it to their social networks, even if they know it has been proven inaccurate (Hassan & Barber, 2021).

The post is something the user already believes to be true

Confirmation bias is when someone confirms a belief they already hold to be true. People are better able to remember information when they can connect it to something they already understand. They also naturally try to fit new information in with their existing knowledge. Even when presented with a balanced viewpoint, people pull out the information that best fits into their current belief system (Chen et al., 2015; Buchanan, 2020b; Stecula, 2021). For example, imagine a person is reading an article about caffeine that includes two facts. The first fact is that caffeine can help with concentration and the second fact is that caffeine can lead to problems with sleeping patterns. The first fact is familiar to the person, they have heard it before, and they believe it because they have experienced that effect. This part will be more ‘sticky’ for them, meaning they are more likely to remember it. But they don’t believe the second fact because it’s new, they haven’t experienced it. This second fact is more likely to be forgotten because it doesn’t fit with what they already know. Confirmation bias can impact the information that appears on social newsfeeds, because the more a person likes a particular type of content, the more they will see similar posts, the more they will think their beliefs are true, and so on and so on (Chen et al., 2015).

Disinformation that confirms what we already believe is repeated, stirs emotions or looks credible plays on human psychology and the way our brains work. It is the reason why those four concepts are the most likely causes for our trust in and sharing of false social media posts. In the next section, we will discuss several other online phenomena that can lead people to believe disinformation.

4.2.2 Online Communities, Affiliations and Echo Chambers

Just as a person is more likely to share disinformation that confirms their current belief system, they also are likely to share information that was posted within a trusted community (Buchanan, 2020b). Many social media users seek out communities that hold similar beliefs. When individuals find a community that shares their own biases they feel a sense of belonging, which fulfills a significant human need (Buchanan, 2020b; Bajwa, 2021). Often, they trust whatever their ‘friend’ has said, and share or engage with posts without considering the authority of the person posting the information (Chen et al., 2015).

While some communities might be positive and encourage exploring differing viewpoints, this is not the case with all online groups. Some communities hold extremist beliefs, which in recent years have led to real world events and consequences. Take, for instance, the Trucker or Convoy protests that occurred in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada in February of 2022. Individuals with very specific agendas began to build followings with like-minded individuals on social media. Over time, an enormous real-life protest developed and gained momentum. Across the country, various individuals with different backgrounds stood on both sides of the debate. Many who supported the convoy felt they were standing up for freedom and described the protests as peaceful and friendly. Did they know that a group of extremists were leading the protests via social media channels? James Bauder and his wife Sandra are said to have been the original organizers. They intended to arrange a demonstration in Canada’s capital city and bring a “memorandum of understanding” to Parliament in hopes of ending vaccine mandates (PressProgress, 2022). They had already been organizing protests throughout Canada in a generally peaceful way in the months prior. It wasn’t until Canadian truck drivers were mandated to become vaccinated to remain employed that more of the Canadian population became involved. Many of the leaders who joined at this time were famed for extremist viewpoints across social media (PressProgress, 2022).

James Bauder and another convoy leader Pat King both claimed that in the lead up to the protests they might not have even believed in the social media posts they created. In interviews both expressed sentiments that they would often create content or make statements to see if those in their community were thinking the same thing (Guerriero & Anderson, 2022). In doing so, these individuals were treading a fine line between harmless conversations (which they were claiming to have) and inciting violence (which occurred). Pat King stated in videos that the only way the convoy in Ottawa could be “solved is with bullets” (PressProgress, 2022, para. 9). He also stated that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau needed to “catch a bullet” (Guerriero & Anderson, 2022, 29:04). Imagine being a supporter of the convoy at its inception, believing it to be a peaceful protest and getting caught up in the excitement of an online community fighting for freedoms. Then imagine that the leaders of the initiative begin to talk about using bullets to end the protest. Has participation in the community now become dangerous? People who participate in online communities must remember to step back and evaluate whether the community they have joined is driven by a specific agenda, to consider if the values of that group are values they would still support if questioned outside of the social media environment.

4.2.2.1 Echo Chambers

Much has been made of the online spaces individuals find themselves in. It is believed that, in drastic circumstances, engaging with content that confirms personal belief systems, unfriending those with whom we disagree and joining communities that make us feel seen or heard, might result in people landing in echo chambers. An echo chamber is a way to define a user’s online social space. Over time, as a social media user engages with certain types of content and ignores other content, they begin to create an invisible user profile which is driven by the algorithms of each platform (Zimmer et al., 2019; Menczer & Hills, 2020). The video below What Is an Echo Chamber helps to describe how algorithms work. It is the job of algorithms to push content that each user will enjoy, so that they will continue to come back for more. For example, a person who believes that healthcare services like CT scans and blood tests should be available for purchase might only like posts that confirm this belief, meaning they will see more posts like that over time, which will continue to confirm their beliefs, disconnecting them from information about the importance of public health systems.

Since echo chambers can place people into opposing online environments pertaining to politics, religion, race, and more, they can become dangerous by contributing to divisions in society (Stecula, 2021). In these circumstances individuals are fed information that confirms their viewpoint so frequently that they feel very strongly their argument is correct. Over time, they become so convinced of the truth in what they are seeing that they refuse to believe anything else.

Recent articles have pointed to the fact that echo chambers might be less widespread than previously thought, particularly in relation to the spread of online disinformation. Some researchers have made the argument that social media is actually ‘information expanding,’ as it opens people up to more viewpoints than they would have been exposed to if not on social media (Ross Arguedas, 2022). In any case, it is important to understand that our social media preferences and behavior have the potential to illuminate certain types of stories over others. Regardless of if a user finds themselves in an echo chamber, the way they behave online still has the potential to lead to inaccurate representation of facts by their chosen online community.

Several of the behaviors discussed in this section are problematic, even if they don’t result in people finding themselves in echo chambers. Studies show that those who gather their information from social media channels only scroll, read, and engage with the pieces that are most interesting to them (Martin, 2018). Many choose to interact with content that appeals to them and refuse to interact with the content of people they disagree with. By hiding content or unfriending an individual, social media users are limiting the information they are exposed to (Fletcher, 2020). This impacts their personal algorithms–affecting what information shows up on an individual’s newsfeed (Fletcher, 2020).

4.2.2.2 Trolls

Some malicious actors, such as Trolls, make a career out of manipulating algorithms to alter the information that appears on people’s social feeds. trolls are groups of people intending to create a strong reaction in those they communicate with. They support the spread of disinformation by developing fake accounts and creating content that stirs emotion (Pelley, 2019). They often share the same information from more than one account to try to increase the repetition and popularity of posts. Many attempt to inflame both sides of an issue, simply to increase engagement with an account (Pelley, 2019; Bajwa, 2021).

Troll accounts often reset their online personas, change their handle, change the description of the account and mass delete posts to maintain a following and spread a different message. Most who follow the accounts (especially on Twitter) don’t notice the change. Below is an example tracked by Canadian journalists who examined a Twitter account that changed three times in a 15-month period (Zannettou & Blackburn, 2018). In this example, all iterations featured far-right viewpoints and used inflammatory hashtags such as #NeverHillary and #NObama. The evolution of the account looked like this:

|

Date |

Account (Handle) |

Profile (Description) |

Following (right before changeover) |

|

May 15, 2016 |

Pen_Air |

National American News |

4,308 |

|

Sept 8, 2016 |

Blacks4DTrump |

African Americans stand with Trump to make America great again! |

9000 |

|

Aug 18, 2017 |

Southlonestar2 |

Proud American and TEXAN patriot! Stop ISLAM and PC. Don’t mess with Texas |

Unknown |

The troll account created strife on issues, but more importantly, gradually gained followers. Changing the focus of the account allowed the creator to appeal to different audiences over time. This is an effective way to contribute to dangerous repetition or at the minimum make sure people are exposed to the content. Remember that the more a person sees something, the more they are likely to believe it.

Some trolls work together to create coordinated efforts to ensure that a user’s algorithm will continue to feed them targeted information (Saurwein & Spencer-Smith, 2021). In these scenarios, there is a specific political or economic agenda. For instance, in Russia, people go to an office each day and are paid to spread disinformation (Brown, 2022). This is known as a Troll Farm. Similar to this practice are troll armies or cyber troops which are groups of people who coordinate and attempt to influence public opinion by spreading disinformation (Brown, 2022). These groups are found throughout the world and are often associated with governments and politics (Bradshaw & Howard, 2017). They spread information on social media, using both real and fake accounts. They may post positive or negative comments to increase engagement on their posts, trolling both sides of an issue to increase division and distrust within a society (Bajwa, 2021). In extreme cases, troll armies may target and harass a specific person to discredit their message (Bradshaw & Howard, 2017). Various experts have identified Russian sponsored troll armies as having a major impact on the public unrest and the spread of disinformation that occurred during the 2016 US election (Stringhini & Zannettou, 2020).

However, trolls are not exclusive to Russia and some individuals troll ‘just for fun’. Individuals who get a thrill out of provoking others, for no political or financial gain are plentiful online and they play a part in the spread of disinformation (Pelley, 2019). Take, for instance, “Tina” who in the quote below is responding to a journalist asking her if her online behavior makes her a troll. She said:

I find in real life, I could stand in the middle of the mall and scream my thoughts, and virtually no one will engage with me. In real life, confrontations scare us because we might be physically hurt, so we cower from them. Online though, people have more courage. It’s like social media gives people pack mentality. So I say contentious things, to get a rise out of people, and prompt comment threads that will go on all day. It’s just something to get me through the workday. Also, I like to upset people and steal their time away. I don’t mean half the crap I say. I’m just sick of being made to feel small by this world because I am different, and by making people feel so desperate to be heard, or have their counter-arguments understood, I am making them feel small and unheard like me. So yes, it is a malicious intent, and I guess I fit your bill as a troll. (Pelley, 2019, para. 4)

What danger does this sort of behavior create in the online environment? In communities?

Bonus fun:

4.2.2.3 Spoofers

Spoofers are another example of malicious characters who impact content that appears on social media feeds. They pretend to be someone else to gain confidence, get access to information, steal data, steal money, or spread malware (viruses). Spam or Phishing emails, which attempt to manipulate people into sharing personal information, are the most common examples of spoofing. On social media, spoofers are often behind fake accounts that attempt to ‘friend’ people to gain access to information. Spoofers might also appear on dating sites as ‘catfish’ which is when someone presents a false image of themselves to gain trust (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.). The main goal of a spoofer is to gather information, infect a computer with a virus, or ask for money (Malwarebytes, n.d.).

When a false news source mimics the design of a reliable news source. Usually using similar graphic styles and company names, making them difficult to recognize quickly.

Fake videos created online where a video of one person is taken and transposed with the face, voice, body (or combination of these) onto a video of someone else. The original video is digitally altered with the intent to portray someone as saying or doing something that they haven’t done.

A psychological phenomenon which postulates that the more a person sees something, even something they already know to be untrue, the more likely they are to believe it.

When someone confirms a belief that they already hold to be true.

An individual’s social media feed or space that has been curated by algorithms which track the content the individual has engaged with. Echo chambers will show or suggest content and information a user has previously shown interest in and can lead to a narrow or one-sided perspective.

Groups of users (actual people), who create fake accounts and engage with others online. Trolls will spread disinformation, argue with other users, and repeat falsehoods or offensive statements to get emotional reactions from other users.

Teams of trolls working together to target algorithms by driving up posts and comments of information that aligns with their agendas. Troll farms can be contracted by political organizations to spread disinformation and arouse emotional responses from other social media users.

Someone who pretends to be someone else (usually someone known or a recognized and trusted organization) in order to get information, steal money, or spread viruses on devices.