Chapter 2: Preventing Injury Protecting Children’s Safety

Introduction

Five W’s of Safety

Why is Injury Prevention Important?

Specific Risks for Injury

Injury in Early Childhood Settings

Duty to Supervise

Staff : Child Ratio

Neighbourhood Walks

Excursions

Excursion Risk Assessment

Active Supervision

Creating an Environment of Yes!

Creating a Culture of Safety

Creating a Safety Plan

Documenting Injuries and Injury prevention.

Teaching Children About Safety

Summary

Resources

References

Chapter Learning Objectives:

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain what active supervision is and what it might look like.

- Discuss how to create a culture of safety.

- Identify common risks that lead to injury in children.

- Describe how understanding injuries can help create a safety plan that prevents future injury.

- Summarize strategies educators can use to help children learn about and protect their safety.

- Recall several ways to engage families in safety education.

- Analyze the value of allowing risky play.

Introduction

Keeping children safe must be a top priority for all early care and education programs. Active Supervision is the most effective strategy for creating a safe environment and preventing injuries in young children. It transforms supervision from a passive approach to an active skill. Staff use this strategy to make sure that children of all ages explore their environments safely. Each program can keep children safe by teaching all staff how to look, listen, and engage.

DID you Know?

What are the common types of injuries in early learning settings?

Injury is defined as “the physical damage that results when a human body is subjected to the energy that exceeds the threshold of physiological tolerance or results in lack of one or more vital elements, such as oxygen”.[1] The Canadian Paediatric Society classifies injuries by their external cause or energy types:

- Falls (Mechanical)

- Struck by/against (Mechanical)

- Poisoning (Chemical)

- Suffocation (asphyxiation, too little energy)

- Fire/hot object/smoke (Thermal/Chemical)

Injuries can be unintentional, intentional or undetermined intent. For the purpose of this discussion on safety and prevention of injury in an Early learning setting, we will focus on unintentional injuries – injuries that are not caused or purpose or had the intention to harm. In later chapters, we will discuss intentional injuries – injuries that are deliberate acts to harm oneself (self-inflicted) or another person (assault) – when we look at child maltreatment.

Why do we need to know this?

Knowing the external cause/energy type and the intent provides us with an understanding of how an injury occurred, this information can then be used to create an injury prevention strategy to keep the children in our care safe.

An example:

Let’s consider the scenario in which a child falls from a playground structure, while playing tag and sustains an injury. In this scenario, the external cause of the injury would be classified as a fall (mechanical energy). Since the fall was not intentional (in that it did not occur with the intention to harm) it would be categorized as an unintentional injury.

By understanding the external cause and intent of this injury, preventive measures can be implemented to improve playground safety. For example, installing safety barriers, ensuring adequate surfacing materials, and implementing age-appropriate equipment can help reduce the risk of falls and minimize the occurrence of such unintentional injuries.

Now if we take the same scenario but change the intent to intentional – another child pushes the child off of the play structure – our focus would be different, instead of focusing on safety barriers and surfacing material we might first focus on addressing the underlying issues such as lack of supervision, reviewing or creating playground safety rules with children.

Five W’s of Safety

Click on the information buttons to view each of the five W’s of safety

Why is injury prevention important?

According to Saskatchewan Prevention Institute “Injury prevention is important because the majority of injuries are predictable and preventable. To be effective at injury prevention, we need to recognize that injuries are avoidable and that we can take action to keep children safe. Injuries are not accidents, inevitable, or part of our fate and destiny. The belief that we have no control over injuries is not true and can be used as an excuse not to take preventative action”.[2] (Saskatchewan Prevention Institute, 2017, pg. 4).

Specific Risks for Injury

Child injuries are preventable, yet 7,294 children (aged 0-9) were hospitalized in Canada (Quebec excluded) for unintentional injuries in 2018/2019 [3].

|

Leading causes of injury hospitalizations among children ages 0-9 years old, in Canada (Quebec excluded) 2018-2019 |

Age Group | |

| <1 | 1-9 | |

| All Injuries (Excluding complications of medical and surgical care) |

1,479 |

6,977 |

| Unintentional injuries (Excluding complications of medical and surgical care) | 1,418 | 6,876 |

| Falls | 389 | 3,246 |

| Suffocation | 196 | 590 |

| Motor vehicle traffic crashes | 15 | 212 |

| Poisonings | 80 | 501 |

| Struck by/against | 26 | 325 |

| Fire/hot object/smoke | 55 | 307 |

| Source: Health and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice (2020) | ||

Car crashes, suffocation, drowning, poisoning, fires, and falls are some of the most common ways children are hurt or killed. The number of children dying from injury dropped nearly 30% over the last decade. However, injury is still the number 1 cause of death among children.[4]

Children during early childhood are more at risk for certain injuries. Using data from 2000-2006, the CDC determined that:

- For children less than 1 year of age, two–thirds of injury deaths were due to suffocation.

- Drowning was the leading cause of injury death between 1 and 4 years of age.

- Falls were the leading cause of nonfatal injury for all age groups of less than 15 years of age.

- For children ages 0 to 9, the next two leading causes were being struck by or against an object and animal bites or insect stings.

- Rates for fires or burns and drowning were highest for children 4 years and younger.[5]

Injury in Early Childhood Settings

Families “are naturally concerned for their child’s safety, particularly when cared for outside of the home. However, children who spend more time in nonparental child care have a reduced risk of (unintentional) injury. This may be because child care centers and family day homes provide more supervision and/or safer play equipment. Nevertheless, injuries in child care settings remain a serious, but preventable, health care issue.”[6]

In the next two chapters, we will examine creating safe environments indoors and outdoors that specifically reduce the risks of injuries, including those introduced in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2 – Preventing Injuries

| Type of Injury | Prevention Tips |

| Sudden Unexpected Infant Death

(SUIDs) |

· Always put infants to sleep on their backs

· Cribs, bassinets, and play yards should conform to safety standards and be covered in a tight-fitting sheet · There should be no fluffy blankets, pillows, toys, or soft objects in the sleeping area · Don’t allow children to overheat[7] |

| Choking | · Keeping objects smaller than 1½ inches out of reach of infants, toddlers, and young children.

· Have children stay seated while eating · Cut food into small bites · Ensure children only have access to age-appropriate toys and materials[8][9] |

| Drowning | · Make sure caregivers are trained in CPR

· Fence off pools; gates should be self-closing and self-latching · Supervise children in or near water[10] · Inspect for any standing water indoors or outdoors that is an inch or deeper. · Teach children water safety behaviors[11] |

| Burns | · Have working smoke alarms

· Practice fire drills · Never leave food cooking on the stove unattended; supervise any use of microwave · Make sure the water heater is set to 120 degrees or lower[12] · Keep chemicals, cleaners, lighters, and matches securely locked and out of reach of children · Use child-proof plugs in outlets and supervise all electrical appliance usage[13] |

| Falls | · Make sure playground surfaces are safe, soft, and made of impact-absorbing material (such as wood chips or sand) at an appropriate depth and are well-maintained

· Use safety devices (such as gates to block stairways and window guards) · Make sure children are wearing protective gear during sports and recreation (such as bicycle helmets) · Supervise children around fall hazards at all times[14] · Use straps and harnesses on infant equipment[15] |

| Poisoning | · Lock up all medications and toxic products (such as cleaning solutions and detergents) in original packaging out of sight and reach of children

· Know the number to poison control (1-800-222-1222) · Read and follow the labels of all medications · Safely dispose of unused, unneeded, or expired prescription drugs and over-the-counter drugs, vitamins, and supplements[16] · Use safe food practices. |

| Pedestrian | · Do not allow children under 10 to walk near traffic without an adult

· Increase the number of supervising adults when walking near traffic · Teach children about safety including: o Walking on the sidewalk o Not assuming vehicles see you or will stop o Crossing only in crosswalks o Looking both ways before crossing o Never playing on the road o Not crossing a road without an adult · Supervise children near all roadways and model safe behaviour[17] |

| Motor-vehicle | · Children should still be safely restrained in a five-point harnessed car seat

· Children should be in the back seat · Children should not be seated in front of an airbag[18] |

Duty to Supervise

Supervision

From the Child Care Regulations, 2015, review:

Section 49 – Duty to Supervise

Section 51 – Maximum Group size

Section 52 – Supervision at Centres

Staff : Child Ratio

In Saskatchewan, the Child Care Regulations 2015, sections 49 – 54 outline the staff-child ratio, adult-child ratio and group sizes for each age group that one (1) adult can safely supervise. The Saskatchewan Child Care Regulations have established minimum educator-child ratios for different age groups to ensure the safety of all children.

The Regulations also outline the staff/adult-to-child ratio for neighbourhood walks and excursions.

Neighbourhood Walks

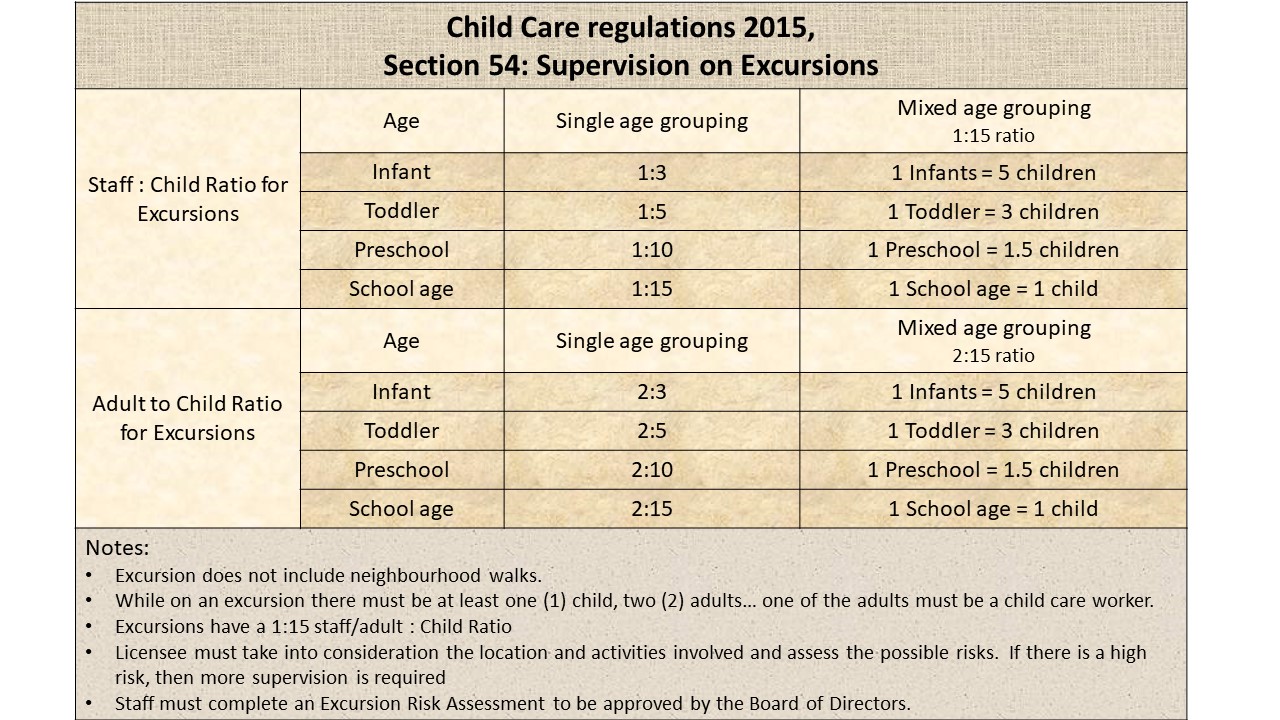

Excursions

When calculating the ratio to ensure children’s safety, you need to remember that the regulations outline the maximum group size and staff-to-child ratios but you also need to take into account that the level of supervision depends on both the age of the children and the risks of the activity. For example, if one staff member was supervising children who are learning to use hammers and saws that educator would not have the maximum number of children doing the activity, instead, they would have a small group while another staff member supervised the remaining children. On the other hand, if you are taking a group of children to a crowded event (i.e. children’s festival) where there is a greater possibility of a child wondering off and getting lost you would need to have additional adults to supervise then you would if you were going to the local community garden that is typically smaller and fenced in with clear visual lines.

Excursion Risk Assessment

Section 54 (8) Supervision on Excursions states:

With respect to an excursion away from a centre, a licensee must:

(a) consider the location and activities involved in the excursion and assess the possible risks to the children associated with that location and those

activities; and

(b) if the risk appears to be greater than usual, supply additional staff or volunteers to accompany the children on that excursion.

To do this educators need to complete an Excursion Risk Assessment form:

The form is used to plan excursions. It allows you to plan for any possible risk there may be. Click the following link to view the PDF version of the Excursion risk assessment form. It outlines when and where you are going, how you are getting there, what are some risks you may encounter and how you can minimize them.

Active Supervision

Children are explorers by default, everything in their environment is new and needs to be explored. Children in early learning environments are also at various stages of development as a result bumps and bruises are inevitable. Our instinct as humans is to protect children, however, in some situations, our attempts to protect children can interfere with their natural development. An example would be a parent’s fear of their child being abducted Our role as educators includes supporting children’s explorations and, at the same time keeping them safe. We do not want to deter children’s investigation of their environments but we want to keep them safe at the same time. One vital way to do this is through Active Supervision.

What is Active Supervision?

Active Supervision is the most effective strategy for creating a safe environment and preventing injuries in young children. It transforms supervision from a passive approach to an active skill. Staff use this strategy to make sure that children of all ages explore their environments safely. Each program can keep children safe by teaching all staff how to look, listen, and engage.

Active supervision requires focused attention and intentional observation of children at all times. Staff position themselves so that they can observe all of the children: watching, counting, and listening at all times. During transitions, staff account for all children with name-to-face recognition by visually identifying each child. They also use their knowledge of each child’s development and abilities to anticipate what they will do, then get involved and redirect them when necessary. This constant vigilance helps children learn safely.

Strategies to Put Active Supervision into Place

Infants, toddlers, and preschoolers must be directly supervised at all times. This includes daily routines such as sleeping, eating, and diapering or bathroom use. Programs that use active supervision take advantage of all available learning opportunities and never leave children unattended. The following strategies allow children to explore their environments safely. Click on the ![]() to reveal details of each strategy.

to reveal details of each strategy.

The video below shows what the 6 strategies of Active Supervision look like in an Early Learning setting (Run-time is 4:20)

The video below shows what the 6 strategies of active supervision look like in an early learning outdoor environment (Run-time is 3:39)

Pause and Reflect:

Read the following scenario and pick out the examples of Active Supervision that Yasmin and Maria used.

What does Active supervision look like? To understand what active supervision might look like in your program, consider the following example:

Maria and Yasmin have taken their three-year-old classroom out to the playground for outdoor playtime. The 15-foot square playground has a plastic climber, a water/sand table and a swing set. Maria and Yasmin stand at opposite corners of the playground to be able to move quickly to a child who might need assistance. The children scatter through the playground to various areas. Some prefer the climber, while others like the swings. Many of the children play with the sand table because it is new. Maria and Yasmin have agreed on a supervision plan for which children they will observe and are always counting the children in the areas closest to them, occasionally raising their fingers to show each other how many children are close to them. This helps them keep track of where the children are, and to make sure no one is missing. If one child moves to a different area of the playground, they signal each other so that they are both aware of the child’s change in location.

Maria has noticed that Felicity loves to play in the sand table. She hears children scolding each other and notices that Felicity throws the toys without looking. As Maria sees Felicity and Ahmed playing at the sand table, Maria stands behind Felicity and suggests she put the toy back in the basket when she is done with it. By remaining close, she is also able to redirect Ahmed who has never seen a sand table before and throws sand at his classmates. Kellan has been experimenting with some of the climbing equipment and is trying to jump off of the third step onto the ground. While he is able to do this, some of the other children whose motor skills are not as advanced also try to do this. To help them build these skills, Yasmin stands close to the steps of the climbing structure. She offers a hand or suggests a lower step to those who are not developmentally ready.

Maria and Yasmin signal to each other five minutes before playtime is over, then tell the children they have 5 minutes left to play. When the children have one minute left, Maria begins to hand out colours that match the coloured squares they have painted on the ground. She asks Beto, a child who has trouble coming inside from playtime, to help her. When the children are handed a coloured circle, they move to stand on the coloured spot on the playground. As the children move to the line, Maria guides them to the right spot. When all children are in line, both Maria and Yasmin count the children again. They scan the playground to make sure everyone is in place, then move the children back into the classroom. They also listen to be sure that they do not hear any of the children still on the playground. Yasmin heads the line and Maria takes the back end, holding Beto’s hand. When they return to the classroom, there are spots on the floor with the same colours that were on the playground. The children move to stand on their matching colours in the classroom. Maria and Yasmin take a final count, then collect the circles and begin the next activity.

Both Yasmin and Maria are actively engaged with the children and each other, supporting the children’s learning and growth while ensuring their safety. They use systems and strategies to make sure they know where children are at all times, and that support developmentally appropriate child risk-taking and learning.

Active supervision during outdoor play is critical. There’s more potential for unintentional injury outside due to the size and nature of outdoor equipment and materials. You should monitor all areas of the space to ensure safety. Be mindful of strangulation hazards such as hoods and drawstrings on clothing, helmets, scarves, skipping ropes, cords, or braided ropes.

Outdoor excursions off-site, such as field trips, require extra supervision. Volunteers often join to improve the adult-child ratio.

Here are some suggestions for you to practice to ensure children’s safety:

- Maintain daily attendance and do frequent head counts

- Secure all exits

- Control entry into the building

- Lock the outdoor play space gate

- Know the procedure to follow if a child goes missing

Active Supervision for Infants and Toddlers

Infant/toddler care is responsive, individualized care. It’s important to think about infants and toddlers that are cared for in small groups with a primary-caregiver system of care and also to think about the flow of the day as being responsive to the individualized needs of the children. Staff work very closely with children throughout the day guiding them through individual or small-group routines and experiences. Staff are providing responsive, individualized care, and they will know each child well. That’s an important piece of both individualized care and active and responsive supervision. They have a good sense of how each child gets through the day, what their abilities are, and what their temperament is. Even as they grow and change from day to day, they’re able to follow each child in their care with an understanding of how it is that they’re growing.

In center-based programs or larger family child care homes, more than one caregiver is working together in a team. The other thing that’s important to remember is the kind of communication that develops between the two educators in a classroom or a family-child care provider and an assistant — a communication that supports a child’s safe movement throughout the day as well as their ability to explore and grow in a nurturing environment.

Adults provide support to each other, particularly at key times of the day, like transitions. All of those important, individualized routines require both adults to work together, such as individual sleeping times, going indoors and outdoors, changing times, feeding and eating times for infants and toddlers, and other times during the day when there may be a particular child that needs individualized care. It’s so important that the staff working with them are working together to support continuity of care.

The environment itself can be a partner in caring for infants and toddlers, particularly when it comes to keeping children safe. We want to create environments that provide places for children to play and be both together and apart but always in full view and within easy reach of a caring and attentive adult.[20]

Creating an Environment of Yes!

An environment of “yes” means that everything infants and toddlers can get their hands on is safe and acceptable for them to use. One way to ensure this is for adults to do ongoing safety checks in group care spaces and provide families with information about doing safety checks of their own. The educator, home visitor, and the child’s family play a vital role in making sure everything is safe, then stepping back to allow exploration.

Sometimes infants and toddlers will use materials in creative ways that surprise us! When educators feel uncomfortable about an activity, they should stop and ask themselves two questions:

- Is it dangerous?

- What are the children learning from this experience?

If it is decided that the activity is safe with supervision, they should stay nearby. They should be thoughtful and open to what the children might be learning. If the activity is not safe, they need to consider what else might address the infants’ and toddlers’ curiosity in the same way. For example, if young toddlers are delighted to discover that by shaking their sippy cups, liquid comes out; an educator may be worried that this water on the floor will lead to a slippery accident. Instead, they might provide squeeze bottles outside or at the water table. The adult is responsible for keeping children safe and encouraging learning through curiosity.

Saying “no” to infants and toddlers or asking them to “share” is a strategy that rarely works. One way to prevent conflict is to reflect on, and then set up, the space where children play in ways that promote “yes!”

- What areas generate the most “no’s” or require the most adult guidance?

- What do the children need and enjoy the most when it comes to playtime?

- Do you have multiple favourite toys?

- Do you have enough places where toddlers can play alone or with a few friends?

- Do you have adequate space for active play?

- Is the room appropriately child-proofed?[21]

It’s important not to become complacent with safety practices. Educators need to keep it fresh, thoughtful, and intentional. This begins with setting up the environment. Classrooms will have unique factors to consider. However, some general considerations include making sure that there is an educator responsible for every part of the space children are in, which may be referred to as zoning, and for every part of the day (including transitions).

How educators position their bodies is really important. They should see all of the children in their care from any position in the room. And when in playing areas, their back should not be to the center of the room, but towards the wall. It is also important to move closer to children as needed (rather than staying in one place and potentially missing out on problems that may arise).

Educators also need to talk to each other, using back-and-forth communication, so that safety information is easily spread through the room. It may seem strange at first, sometimes, for educators to talk to each other; but, it’s incredibly helpful for active supervision – when there are either changes in staff or children’s routines, changes in roles, or changes during transitions.

One of the main purposes of zoning was to help all children be engaged and to minimize unnecessary wait times. When all staff know their roles in the classroom with zoning and tasks are getting handled, children are engaged and the unsupervised wait time is really minimized.

During transitions or routine changes, educators need to have a heightened awareness. Transitions are challenging times for both children and their educators, so the risk to safety increases. One thing that educators can think about is how they can minimize the number of changes so that there aren’t as many transitions happening in the classroom. There should be plans for what adults will do, before, during, and after transition times.[23]

Creating a Culture of Safety

The topic of keeping children safe is only partly about policies rules, and oversight. Those things are important. But most important of all, this is about staff, the people who work directly with children and families. Those people must be supported with opportunities for reflection, professional development, and chances to think about the work they do and why that work is so important. What is challenging in that work, and what comes to them easily? It’s the ability of programs to recognize and analyze challenging conditions and be able to make improvements.

Programs must make sure that staff have that sense of commitment and responsibility, and that they have the ability to ensure children are thriving is critical. They have to help make sure staff remember why we do the work, to be curious about children’s interests, needs, and ideas, to have the opportunity to be creative, to enjoy children and each other’s humour every day. These things, in addition to the policies and procedures, will allow staff to be fully present with children. Adults who can be fully present will keep children physically and emotionally safe and thriving.

The first step to doing this is to create a culture of safety. In this context, culture means the set of shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices that characterize a program; the way things work in that program and in that community. Experts and researchers have demonstrated that the culture of an organization plays a key role in all successful safety initiatives.

This is done by involving every staff member and committing to safety at all levels. Programs shouldn’t assume that nothing will ever go wrong. In fact, they should plan that something is going to go wrong. The goal is to create environments where there is zero harm, making it as hard as possible for things to go wrong.

Directors, managers, staff, and families must all embrace the belief that children have a right to be safe. All the adults in the program, the program leaders and staff, know that they are responsible for every child, all day, every day. People understand their roles and responsibilities in keeping children safe and embrace each of the 10 actions outlined in Table 2.1, that together support a culture of safety. This approach is holistic. It’s integrated and community-centered. It isn’t an add-on. It’s not a burden. It’s a way of doing business so children don’t get hurt.[25]

Table 2.1: 10 Actions for a Culture of Safety[26]

| 1. Use Data to Make Decisions: Program and incident data serve as an important resource to help managers and staff evaluate children’s safety. |

| 2. Actively Supervise: Children are never alone or unsupervised. Staff position themselves so that they can observe, count, and listen at all times. |

| 3. Keep Environments Safe and Secure: Programs create, monitor, and maintain hazard-free spaces. |

| 4. Make Playgrounds Safe: Regularly inspected, well-maintained, age-appropriate and actively supervised outdoor play spaces allow children to engage in active play, explore the outdoors, and develop healthy habits. |

| 5. Transport Children Safely: Programs implement and enforce policies and procedures for drivers, monitors, children, and families using school buses, driving to and from the program, or walking. |

| 6. Report Child Abuse and Neglect: Managers and staff follow mandated reporting statutes and procedures for reporting suspected child abuse and neglect. |

| 7. Be Aware of Changes that Impact Safety: Staff anticipate and prepare for children’s reactions to transitions and changes in daily routine, within and outside of the program. |

| 8. Model Safe Behaviors: Staff establish nurturing, positive relationships by demonstrating safe behaviors and encouraging other adults and children to try them. |

| 9. Teach Families about Safety: Staff engage families about safety issues and partner with them about how to reduce risks to prevent injuries that occur in the home. |

| 10. Know Your Children and Families: Staff plan activities with an understanding of each child’s developmental level and abilities, and the preferences, culture, and traditions of their families. This includes everything from maintaining current emergency contact information to understanding families’ perceptions about safety and injury prevention. |

Creating a Safety Plan

Early care and education programs have an obligation to ensure that children in their care are in healthy and safe environments and that policies and procedures that protect children are in place. Using a screening tool, programs can identify where they need to make changes and improvements to ensure children are healthy and safe while in their care. A checklist such as the one modified from Head Start’s Health and Safety Screener in Appendix C can be used for this purpose.[27]

Programs must become familiar with the hazards to children that are specific to their population and location. Considerations for this plan include the type of early education program, ages of the children served, surrounding community, and family environments.

If any hazards are found upon screening, programs can make modifications to remove hazards or use safety devices to protect children from hazards. Care should be taken to ensure that the modifications include children with disabilities and special needs.

It will also be important to use positive guidance to help modify behaviours that put children’s safety at risk. Educators can use role-modeling and communication to teach children how to respond to situations, including emergencies, that put their safety at risk.

Early childhood programs must continue to monitor for safety. This includes regular screening for safety and analysis of data surrounding injuries. Educators must continuously monitor for conditions that may lead to children being injured and examine both the behaviours of children and adults in the environment.[29]

Documenting Injuries & Injury Prevention

When a child is injured, it is important to document the injury. This documentation is provided to families, typically in the form of a Minor injury report or Injury Unusual occurrence report See Appendix D for an example. These should document:

- Who was involved in each injury? (child/children; staff, volunteers, family members)

- Where did the injury occur?

- What happened? (What was the cause?)

- What was the severity of each injury?

- When did each injury occur?

- Who – e.g., what staff were present and where were they at the time of each injury?

- What treatment was provided? How was the incident handled by staff?

- How could each injury have been prevented? What will be done in the future to prevent similar injuries?

- Who was notified in the child’s family? When? How?

It is important to keep these reports to analyze them to:

- identify location(s) for high risk of injury.

- pinpoint systems and services that need to be strengthened.

- develop corrective action plans

- and incorporate safety and injury prevention into ongoing monitoring activities.[30]

Hazard Mapping

One such process to do this is hazard mapping, which is an approach to prevent injuries by studying patterns of incidents.

Step One – Identify High-Risk Injury Locations

- Create a map of the classroom, center, or playground area. Label the various places and/or equipment in the location(s) that is being mapped. Make the map as accurate as possible.

- Place a “dot” or “marker” on the map to indicate where each specific incident and/or injury occurred over the past 3-6 months (or sooner, if concerns arise).

- Look at the severity of the injuries.

- Identify where most incidents occur.

Step Two – Identify Systems and Services that Need to be Strengthened

- Review the information on the injury/incident reports for areas with multiple dots.

- Consider what policy and practices are contributing to injuries/incidents.

Step Three – Develop a Corrective Action Plan

- Prioritize and select specific activities/strategies to resolve problem areas.

- Develop an action plan to correct the problem areas you identified. Include each of the activities/strategies selected in this corrective action plan. Identify the steps, the individuals responsible, and the dates for completion.

- Create a plan for sharing the corrective action plan with staff and families.

Step Four – Incorporate Hazard Mapping into Ongoing Monitoring

- Determine if any additional questions should be added to injury/incident report forms to obtain this missing information.

- When developing corrective action plans, consider prioritizing more serious injuries, even if they have occurred less often.

- Make sure there is a reduction in injuries and/or incidents and the severity of the injuries with a corrective plan.[31]

Teaching Children about Safety

While it is the adult’s responsibility to keep children safe and children should not be expected to actively protect themselves, educators should help children develop safety awareness and the realization that they can control some aspects of their safety through certain actions. The earlier children learn about safety, the more naturally they will develop the attitudes and respect that lead to lifelong patterns of safe behaviour.

Safety education involves teaching safe actions while helping children understand the possible consequences of unsafe behaviour. Preschoolers learn through routines and daily practice and by engaging in language scripts and following simple rules. These scripts and rules may be communicated through voice, pictures, or signs. Children learn concepts and develop skills through repetition, then build upon these as concepts and skills become more complex.

Preschoolers need help to recognize that safe play may prevent injury. Educators can promote independence and decision-making skills as children learn safe behaviours. Educators can explain that children can make choices to stay safe, just as they wash their hands to prevent disease, brush their teeth to prevent cavities and eat a variety of foods to help them grow strong and healthy.

Preschoolers can learn to apply a few simple and consistent rules, such as riding in a car seat and wearing seat belts, even though they are too young to understand the reasons for such rules. For example, four-year-old Morgan says, “Buckle up!” as she gets into a vehicle. Although Morgan lacks the skill needed to buckle the car seat buckle and does not understand the consequences of not being safely buckled into her car seat, she is developing a positive habit. Safety education in preschool focuses on behaviours the children can do to stay safe. It involves simple, concrete practices that children can understand.

The purpose of safety rules and guidance is to promote awareness and encourage developmentally appropriate behaviour to prevent injury. Educators may include separate rules for the classroom, playground, hallways, buses, or emergency drills. Limit the number of rules or guidelines, but foster consistency (e.g., three indoor rules, three playground rules) and base them upon the greatest hazards, threats, and needs in your preschool program and community.

Safety guidance is most effective when educators have appropriate expectations and safety rules are stated in a positive manner. For example, an appropriate indoor safety rule might be stated, “We walk indoors,” rather than the negative, “Do not run indoors.” On the playground, a rule might state, “Go down the slide on your bottom, feet first.” As children follow these rules, acknowledge them for specific actions with descriptive praise (e.g., “Kevin, you sat on the slide and went down really fast! That looked like fun!”).

State rules clearly, in simple terms, and in children’s home languages; include pictures or icons with posted rules to assist all children’s understanding. Children often are more willing to accept a rule when they are given a brief explanation of why it is necessary. Gently remind children during real situations; with positive reinforcement, they will begin to follow safety rules more consistently. As children develop a greater understanding of safety rules, they begin to develop self-control and feel more secure.

Adults are fully responsible for children’s safety and compliance with safety rules and emergency procedures. Safety education for children, which includes rules and reinforcement of verbal and picture scripts in children’s home languages (including sign language), is essential for handling emergency situations. Through practice and routines, children are better able to follow the educator’s instructions and guidance. It is essential that educators evaluate each child’s knowledge and skill in this area, and provide additional learning activities as needed to ensure that all children can follow emergency routines.

Here are some strategies that educators can use to help children learn about safety:

- Incorporate safety into the daily routine.

- Involve children in creating rules

- Provide coaching and gentle reminders to help children follow safety rules.

- Acknowledge children’s self-initiated actions to keep themselves and others safe (such as pushing chairs in and wiping up spills)

- Provide time for children to practice safety skills (such as buckling seat belts)

- Introduce safety concepts and behaviours in simple steps.

- Role-play safety-helpers.

- Define emergency and practice what children should do in emergency situations.

- Introduce safety signs.

- Incorporate musical activities and safety songs.

Because of their level of cognitive development, many young children cannot consistently identify dangerous situations. They may understand some safety consequences and can learn some scripts. But adults must be responsible for their safety. Children often act impulsively, without stopping to consider the danger. By learning and following simple safety rules (e.g., taking turns, wearing a helmet) and practicing verbal, visual, or sign-language scripts, children establish a foundation of lifelong safety habits.[33]

Engaging Families

|

|

Risky Play and Children’s Safety: Balancing Priorities for Optimal Child Development

|

|

Pause to Reflect

|

Summary

Active supervision is critical to keep young children safe. When programs create a culture of safety, they go beyond following regulations and policies, by making a commitment to protecting safety so that children don’t get hurt. There are some common risks to safety that educators should be aware of (and that will be covered in more depth in the next two chapters). When early care and education programs create a safety plan using data they have gathered by documenting and analyzing the injuries children get, they can make changes to help protect children’s safety.

While adults have the ultimate responsibility for safety, children can be taught about and families can be engaged in protecting children’s safety. Educators must also consider the value of risk play when making decisions about what action to take to keep children safe.

|

|

Resources for Further Exploration· Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards – Guidelines for Early Care and Education Programs: https://nrckids.org/files/CFOC4 pdf- FINAL.pdf · Head Start’s Safety Practices in the Early Childhood Learning and Knowledge Center: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/safety-practices · Program Administrator Guide to Evaluating Child Supervision Practices: https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/accreditation/early-learning/Supervision Resource_0.pdf · Supervising Children in Child Care Centers (Licensing video): https://ccld.childcarevideos.org/child-care-center-operators/supervising-children-in-child-care-centers/ · Health domain in the California Preschool Curriculum Framework Volume 2: https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/cd/re/documents/psframeworkvol2.pdf · CDC: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/index.htm · Safe States Alliance: https://www.safestates.org/default.aspx

|

References

- Child and your injury prevention: A public health approach, Yanchar N., Warda L., & Fuselli P., Canadian Paediatric Society ↵

- Child injury prevention program and action guide, Saskatchewan Prevention Institute ↵

- At-a-glance - Injury hospitalizations in Canada 2018/2019, Ziaoquan Yao et. al., 2020, Government of Canada ↵

- Child Injury by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain. ↵

- CDC Childhood Injury Report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain. ↵

- Health implications of children in child care centres Part B: Injuries and infections. (2009). Paediatrics & child health, 14(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/14.1.40 ↵

- California Dept. of Public Health MCAH. (2014). What Child Care Providers and Other Caregivers Should Know. Retrieved from https://cchealth.org/sids/pdf/Child-Care-SIDS-Booklet.pdf. ↵

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2020). Safety and Injury Prevention Curriculum. Retrieved from https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-child-care/Pages/Safety-and-Injury-Prevention.aspx ↵

- Anderson, K. (2020). Choking: Knowing the Signs and What to Do. Retrieved from https://www.chla.org/blog/rn-remedies/choking-knowing-the-signs-and-what-do ↵

- Drowning Prevention by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain. ↵

- California Childcare Health Program. (n.d.). Prevent Drowning. Retrieved from https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/drownen081803_adr.pdf ↵

- Burn Prevention by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain. ↵

- Safety and Injury Prevention by Kimberly McLain, Erin K. O’Hara-Leslie, & Andrea C. Wade is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Fall Prevention by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain. ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2020). Fall Safety for Kids: How to Prevent Falls. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/infant-and-toddler-health/in-depth/child-safety/art-20046124 ↵

- Poisoning Prevention by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain. ↵

- Safety Tips for Pedestrians by the Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center is in the public domain ↵

- Child Passenger Safety: Get the Facts by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain ↵

- California Infant/Toddler Curriculum Framework by the California Department of Education is used with permission. ↵

- Keeping Babies Safe: Active Supervision for Infants & Toddlers by the Dept. of Health and Human Services is in the public domain. ↵

- Environment as Curriculum for Infants and Toddlers by the Office of Head Start is in the public domain. ↵

- California Infant/Toddler Curriculum Framework by the California Department of Education is used with permission. ↵

- Active Supervision for Preschoolers by the Dept. of Health and Human Services is in the public domain. ↵

- Infant/Toddler Learning and Development Program Guidelines by the California Department of Education is used with permission. ↵

- Creating and Enhancing a Culture of Safety Head Start Town Hall Meeting: September 12, 2018 by the Dept. of Health and Human Services is in the public domain. ↵

- 10 Actions to Create a Culture of Safety by the National Center on Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain. ↵

- Health and Safety Screener by the Office of Head Start is in the public domain. ↵

- Infant/Toddler Learning & Development Program Guidelines by the California Department of Education is used with permission. ↵

- Robertson, C. (2013). Safety, nutrition, and health in early education (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ↵

- Hazard Mapping for Early Care and Education Programs by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain. ↵

- Hazard Mapping for Early Care and Education Programs by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain. ↵

- 150917-M-UF252-286.JPG by Nathan L. Hanks Jr. is in the public domain. ↵

- California Preschool Curriculum Framework Volume 2 by the California Department of Education is used with permission. ↵

- California Preschool Curriculum Framework Volume 2 by the California Department of Education is used with permission. ↵

- Adventure Playground Natural Free Photo by MadCabbage is in the public domain. ↵

- Brussoni, M., Olsen, L. L., Pike, I., & Sleet, D. A. (2012). Risky Play and Children’s Safety: Balancing Priorities for Optimal Child Development. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(9), 3134–3148. doi:10.3390/ijerph9093134. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/9/9/3134 ↵